What is more countercultural than submission?

In a time of unalienable rights and unfettered individuality, voluntary abdication of power, rights or personal expression is relatively unthinkable.

These norms seep into church despite the fact that submitting, yielding and weakness are Gospel bedrock. The central image of our faith is our Saviour, not with a fist raised defiantly but arms spread on a cross, nailed there by overlording oppressors.

At the crux of his ministry on Earth, Jesus submitted to earthly powers. He healed the ear Peter chopped off. He carried his cross. He spoke little.

Then he exhibited a kind of power that changed history.

Since then, submission and surrender have too often been distorted by religion, at unimaginable cost. Can they be salvaged in some form?

In an interview on page 12, David Fitch, a neo-Anabaptist who teaches at Northern Seminary and pastors a majority-Black church in the Chicago area, says the way to avoid the abuse of power is to embrace a particular type of submission and a bold surrender to God’s power.

Tough sell.

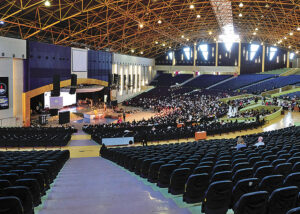

Though Fitch clearly warns against harmful kinds of submission, and his goal is to prevent abuse, biblical passages about submission are, he admits, “much-despised.” When Fitch spoke at the Canadian Mennonite University Renew Conference in February, not everyone was on board.

In conversation, Fitch rooted his message in his own story of being corrupted by power and then saved by grace. He challenges Christians to stop straining to control outcomes and instead to make space for God through presence and prayer.

Fitch leaves a specific role for worldly power but, ultimately, calls us to something greater.

I find it a compelling message, relevant to workplace, social change, congregation and family. I’ve been experimenting.

His most recent book, Reckoning with Power (excerpt on page 15), reminded me of the witness of Archbishop Romero in El Salvador during violent conflict between forces aligned with the elite and peasants pushed to the margins. Romero found Christ among the peasants, but he also clearly said that lefty economic liberation would be worthless if people’s hearts remained estranged from God. Political change was important; inner conversion was vital.

I thought too of Gandhi, who, in a wildly counter-intuitive use of power, actively recruited volunteers from among his fellow Indians to serve the oppressive class, in one case by caring for wounded soldiers of the government he was trying to change. He appealed to the upside-down power of service and compassion.

While this is not an example Fitch uses, I wonder sometimes about how we might serve adversaries, trusting something far beyond our abilities to control and manage outcomes.

Underlying Fitch’s challenge is a question of the extent to which we believe in God’s power to redeem and sanctify people and social realities.

On February 14, Desalegn Abebe, president of Meserete Kristos Church in Ethiopia, released an article addressing the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) HR controversy. (See articles).

Starting with biblical reflections and words from Anabaptist thinkers, Pastor Abebe acknowledges that MCC “represents a global heritage” for Anabaptists worldwide, then says, “MCC’s recorded handling of whistleblowers and survivors testifies to an institutional culture more invested in control of procedure than in justice.”

He says he is “struck by the culture of silence—instances where voices that should have spoken out remained unheard.”

The article says, “MCC is presented with a decision today: follow the route of institutional drift or embark on the radical accountability its Anabaptist heritage requires.”

Pastor Abebe’s recommendations include an independent, public investigation and survivor-led restoration.

Pastor Abebe is head of the largest church body in Mennonite World Conference and is held in highest regard in the international Anabaptist community.

The article first appeared on the website of MCC Abuse Survivors Together. Pastor Abebe provided CM with detailed information about the conversations and firsthand observations that informed his article. He insisted on editorial scrutiny to “ensure clarity and accuracy.”

In late February, MCC released “Committed to learning, changing and growing,” an 11-page response to ongoing criticism. In it are words of apology: “We apologize to any workers who experienced pain when our systems were slow, unresponsive or dismissive.”

MCC has stated that “the claims of systemic abuse are unequivocally false.” The organization has hired Jes Stoltzfus Buller to design a listening process.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.