I was delivering a sermon on the story of Zacchaeus last October when I realized that when I talked about Zacchaeus, I was actually thinking about, and picturing, my father.

Though not short in stature, my father, like Zacchaeus, was a man whose occupation was often controversial in his community. My father, Milo Shantz, who died in 2009, was a businessman.

For years, his main business was turkeys. He and his brother Ross founded Hybrid Turkeys which is now the world’s largest exporter of turkey breeding stock. He sold that business in 1981 when I was 9. He then focused largely on property development in and around St. Jacobs, Ontario.

He was also intensely involved in church and church-related organizations. He served as treasurer of what was then the Mennonite Conference of Ontario, chair of Mennonite Economic Development Associates, and on various committees and boards. Together with his brother, he established a charitable foundation that gave most of its donations to Mennonite church-related causes.

Late in his life, my dad told me that when he was a teenager in the 1950s, he saw that friends and contemporaries of his, like Ralph Lebold and Herb Schultz, would go on to seminary to become ministers and church leaders. My father knew that this wasn’t his path. He had a learning disability that made school difficult. He only completed Grade 8. Knowing his skills and interests lay elsewhere, he resolved that he would serve the church through business.

Mennonite tourism

By the 1970s, the economy in St. Jacobs was faltering. Businesses were closing. Around this same time, the St. Jacobs and Elmira areas began to see a growth in tourism. People would drive from Toronto to “see Mennonites.” Local Mennonite leaders became concerned that as tourism grew it would become exploitative.

Realizing that tourism was coming whether they liked it or not, these church leaders reasoned that it would be better if a Mennonite had a role in shaping the local tourism sector.

That’s how my father became involved. Encouraged by certain church leaders, he saw this role as the last act of his career.

With help from many people, he started The Stone Crock Restaurant and an interpretive centre now called The Mennonite Story. He repurposed historic buildings as space for artists and artisans. He was behind the expansion of the St. Jacobs Farmers Market.

St. Jacobs went from being a quiet village to a place that was frequently crowded. I think it would have happened whether my father had been there or not, but he became the face of change.

Rumours

I grew up in St. Jacobs, and learned at a young age that not everyone liked what my father did. Two examples:

In 1987, his company opened a restaurant that had a liquor license. Many in the local church disapproved. Around the same time, my parents began attending a different congregation. For years, a persistent rumour in town maintained that my parents had been quietly shunned from St. Jacobs Mennonite Church because of the liquor license.

Then, in the 1990s, the company borrowed to purchase land on the Woolwich-Waterloo border, with a vision to build housing for seniors. My father could not get municipal approval for that project, and his company was caught with the carrying costs of vacant land. So the company was forced to sell, and the only interested buyer was a developer of big box stores.

This generated anti-sprawl opposition, much of it directed at my dad. Many believed my dad was a land speculator seeking to enrich himself. The reality was that his company’s financial situation was drastic. By the time the project was approved, the original offer had expired. The buyers took advantage and cut their original offer substantially. My father felt he had no choice but to accept it.

The land is now home to a Walmart. My father returned to his investors, his employees and his family believing that he was a failure.

The business of belonging

Those are just two situations I remember in which my father felt like he didn’t quite belong in his community. I recall his reluctance to go to church some days because he didn’t always know where he stood with people and he didn’t want to face their judgments.

It may seem strange to say that Milo Shantz often felt like he didn’t belong. He was, after all, a respected lay leader in the church and a well-known local business person.

But if Jesus had come to St. Jacobs and called out to Milo saying, “I’m coming to your house for dinner,” I think that many in the crowd would have grumbled like they did when Jesus called out to Zacchaeus.

In Luke’s account of Jesus’ journey from Galilee to Jerusalem, Jesus repeatedly encounters and affirms outsiders and outcasts of various description: Samaritans, widows, the terminally ill and disfigured. He affirms people with sketchy occupations: Roman soldiers, prostitutes and Zacchaeus the tax collector. All of this reveals his mission “to seek out and save the lost”—as Luke repeatedly puts it—all to the consternation of the Pharisees and the puzzlement of the slow-witted disciples.

That phrase, “save the lost,” can cause problems for us. It’s easy to assume that outcasts and outsiders mostly have themselves to blame for being lost. Their own bad choices led them astray.

If I identify as an insider, this is a soothing thought. It restores my sense of superiority over the outsider. It allows me to forget the troubling idea that the outsider might actually be more faithful than me. This thinking enables me to invite outsiders in, provided that they change themselves to fit my expectations.

But the whole point of the encounters Jesus has with outsiders on the journey to Jerusalem is to highlight and affirm the faith and faithfulness of people the community had lost sight of. Jesus tells them: “You, too, are a son of Abraham.” “Your faith has saved you.” “Your sins are forgiven.” In other words, you have nothing to be ashamed of.

The wee little man

Zacchaeus was the chief tax collector in the city of Jericho. As we’ve all been taught, tax collectors were rich, and they were reviled because they extracted punishing taxes in collaboration with the Romans.

Ironically, the name “Zacchaeus” is derived from the word zakkai, which in Hebrew evokes meanings like “clean,” “innocent” and “righteous.”

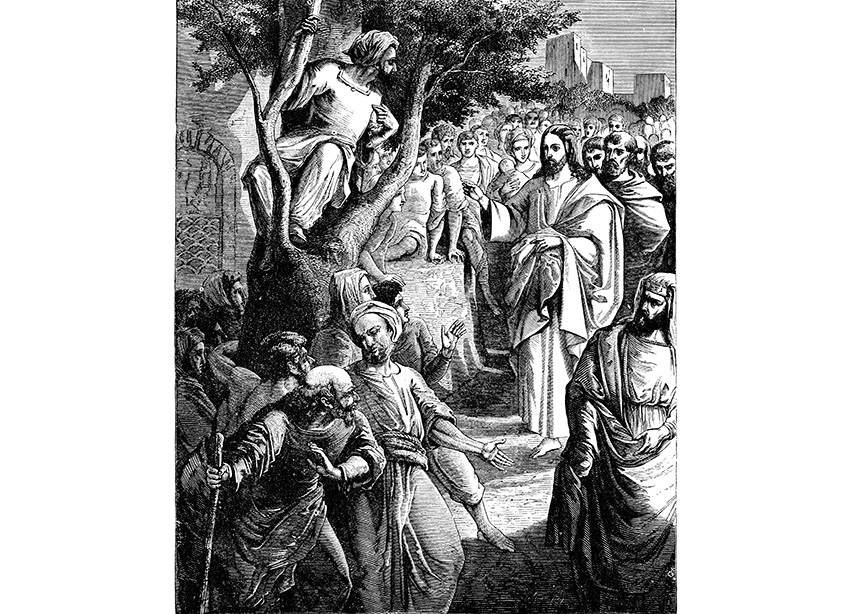

You know the story: Zacchaeus climbs a sycamore tree to get a good view of Jesus. Jesus sees him, calls him down, and says “I’m coming to your house.” Zacchaeus comes down, but the crowd grumbles. Why, they ask, would Jesus go to this man’s house.

At this, Zacchaeus makes the impulsive decision to change his ways. He declares that he will give half his money to the poor, and pay back four times what he took from all those he cheated. Jesus, pleased with this repentant sinner, declares, “Today salvation has come to this house.”

That’s the customary reading. But elements of this reading have always bothered me. Firstly, the story has a transactional feel to it. Zacchaeus gives his money away, and in exchange, Jesus proclaims his salvation. But in many other Gospel stories, salvation is more or less unconditional. Jesus doesn’t heal the servant of the Roman centurion on the condition that the centurion quits his job as a policeman for an oppressive colonial power.

Secondly, I’m uncomfortable that the story seems to reward the graceless crowd. In our normal reading, Zacchaeus makes his promises in response to their grumbling, not in response to Jesus’ call. But the crowd is almost always wrong in all the other stories. This doesn’t fit the pattern.

Another reading

At a recent lecture by Father James Martin, a Roman Catholic priest, I learned of an alternative interpretation of the Zacchaeus story. This reading comes from the noted Jesuit scholar Joseph Fitzmyer, who wrote a magisterial two-volume commentary on Luke in 1986.

In many translations, Zacchaeus says: “Look, I will give half of what I own to the poor.” But Fitzmyer noticed that in the original Greek, Zacchaeus speaks in the present tense: “Look, I give half of what I own to the poor.”

Fitzmyer also stressed the use of “if” in his next promise. Zacchaeus says: “If I have defrauded anyone, I pay it back fourfold.”

This raises the intriguing idea that Zacchaeus isn’t repenting at all. What if being recognized and welcomed by Jesus gave Zacchaeus the courage to defend himself against the crowd?

According to Fitzmyer, Zacchaeus might be saying, “Look, I may be a sinner, but I always give half of my possessions to the poor. And if you can prove that I’ve defrauded anyone, I’ll pay them back four times as much.”

What if the crowd had this guy all wrong? What if Zacchaeus really is “clean”, “innocent” and “righteous” despite his seedy profession?

What if Zacchaeus was living righteously the whole time, using his position and influence to redistribute wealth among those who most needed it?

I can imagine the back-story: Zacchaeus sees that the Romans are there to stay, so becomes a tax-collector in the hope of making things better than they otherwise would be by being an honorable tax collector.

What if, instead of expecting Zacchaeus to change his ways, Jesus recognized great value in Zacchaeus as he was, a person who put his street smarts and business sense to the service of God?

You might resist this interpretation, as many scholars do. Fitzmyer spends several paragraphs taking up objections to his reading of the story.

Why do we want to object?

As Fitzmyer wrote: “Part of the problem is the modern reader’s reluctance to admit that the Lucan Jesus could declare the vindication of a rich person who was concerned for the poor.”

Work in the world

What attracts me to this understanding of Zacchaeus is that it aligns the story with Jesus’s other encounters with people on the margins, in which he recognizes them as people with unique gifts who belong in the Kingdom.

So, what is my point here, apart from working through some personal family history, and maybe revealing more that I intended about my own inner psychology?

I’m not saying that business is beyond criticism, or that the church should bless everything business people do, or that the church should bless business as an end in itself, with the goal of accumulating wealth. That would be contrary to the Gospel.

My point is to provoke conversation and reflection about the working lives of the people in our congregations. We spend much of our lives at work, but I can’t remember the last time we had a serious conversation in my congregation about our occupations, and how we live as Christians in our workplaces.

Jesus commended a Roman soldier for his great faith; I suspect that we’d have a hard time doing the same. Just as business owners can end up on the edges of church because of their professions, the same can happen to people who work for large corporations. Our congregations include software engineers working for “big tech,” farmers working in “big ag,” urban planners working for large land developers, geologists working for “big oil,” and scientists working for “big pharma.”

Business people pose a challenge for Mennonite churches. I think that’s partly because they are very much “in the world,” facing practical dilemmas and pragmatic choices all of the time. Yet I believe that if we asked them, most would say their faith matters in their work, and they think deeply about what it means to be faithful in their occupations. They might also be wary of having that conversation in a church setting, for fear of being misunderstood or misjudged.

Can our congregations be a space for these conversations? What can our churches do to seek out and save those who might be lost to us because of their careers and vocations?

Marcus Shantz serves as president of Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo, Ontario. This article was adapted from a presentation given to Mennonite Church Eastern Canada pastors in January 2023.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.