The first Sunday of Advent marks the beginning of the Christian year, so it would be appropriate to greet each other with the recognition that a new year has begun.

Advent is the most Jewish of Christian seasons. Yet we are accustomed to approaching Advent in a way that strips it of its Jewish character, and we end up with a version of Christianity that is somehow fundamentally at odds with itself.

A church that has lost a sense of the Jewish character of Advent loses the ability to wrestle with a particular set of tensions and ambiguities essential to its being the church. When Christianity came to define itself over against Judaism, more than anything else, it lost a robust sense of the messianic. Christianity’s identification of Jesus as the Messiah has all too often had the effect of initiating an erasure of the very concept of messiah. By messianic, I mean to point to a sense of radical interruption—an inversion of the “laws” of history, a revolutionary change that undoes and transforms the ways we have become accustomed to thinking and acting.

What are we waiting for?

We think of Advent as a season of waiting. We speak of it by invoking notions of preparation and expectation, of anticipation and longing. This is appropriate: Advent names an expectation of an event that is to come. It is a preparation for an arrival that we are still waiting for. But things start to get interesting and difficult when we ask questions like these: What are we waiting for, and why do we wait? How are we to prepare for this event that is to come? What sort of posture does this waiting require?

The starting point from which we must attempt to answer these questions is, of course, the recognition that Advent is a time of preparation and waiting for Jesus, the Messiah. But I’m struck by how easy it is to think about this season in ways that minimize, even cancel out, a sense of the messianic character that is necessary if Jesus is to be what we Christians confess him to be. We cancel out the logic of the messianic when we think of preparation and expectation in terms of one coming who is known in advance of his arrival. We cancel out the logic of the messianic when we think of the Messiah as someone we will surely recognize. And we cancel out the logic of the messianic when we think of Advent as preparing for something that we are striving for, a longing for something that we are responsible to bring about.

But this approach is exactly what some Advent texts warn us against. They plead with God not to be angry—even though God has every right to be angry. The psalmist asks, “O Lord God of hosts, how long will you be angry with your people’s prayers?” (80:4). Isaiah appeals to God: “Do not be exceedingly angry, O Lord, and do not remember iniquity forever” (64:9). These texts involve confession: “We have sinned.” They turn on a recognition of Israel’s transgression and need for restoration.

Why are the people in need of restoration?

Why is God angry? Why are the people of Israel in need of restoration? They need restoration because they have taken their future into their own hands. They have tried to reach God. They have become impatient. They have forgotten that their very existence rests on their being chosen, called out from the nations. They have forgotten that God comes to God’s people, not the other way around. They have, in short, failed to let God be God.

Isaiah is clear about this reality. He emphasizes the fact that God arrives in ways we do not expect: “When you did awesome deeds that we did not expect, you came down, the mountains quaked at your presence. From ages past no one has heard, no ear has perceived, no eye has seen any God besides you, who works for those who wait for him” (64:3-4).

God’s deeds are unexpected. God comes down. God works for those who wait. We cannot see or hear any god but God. Or rather, when we try to see or hear God, we can be confident that it is not God whom we will see or hear. This is why we are to wait for God to come to us: If we rush to meet God, we invariably find something other than God.

Paul’s letter to the Corinthians echoes a similar theme: “God is faithful; by him you were called into the fellowship of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord” (I Corinthians 1:9).

And Mark also reflects this conviction: “But about that day or hour no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father. Beware, keep alert; for you do not know when the time will come” (13:32–33).

The danger is us

Do we see Advent as a dangerous time? I suspect most of us do not. But here we are being told to beware, keep alert and be watchful. Apparently, danger is lurking. And it seems that the danger is us, and it is linked to the fact that our knowledge is not nearly as secure as we think it is. More than anything else, we are confronted with our intractable human capacity for self-deception.

As we enter into the time of expectation that is Advent, we are confronted with our sinfulness: We yearn for a messiah whom we will recognize. We want a messiah who reflects what we would identify as best about ourselves. We long for a messiah who seems familiar, someone we feel like we know. But Advent biblical passages seem to cut in the opposite direction. This is why Advent is dangerous: It all too easily turns into a longing for and anticipation of the Jesus we think we’ve got figured out. It is exactly for this reason that we are called to beware, remain watchful and keep alert.

We tend to think of Advent as a time when we gradually come closer to God, a God who comes to us in human form in Jesus. But Advent begins by confronting us with the anger of God. If these passages underscore anything, it is God’s distance or difference from us. The emphasis is not on a God with whom we are becoming increasingly familiar, but on a God who remains exceedingly strange.

It is in a spirit of confession that we come to this season. Advent is a time of preparation that requires us to confess our tendency to forget God, or to turn God into something familiar. Advent brings us face to face with our insatiable desire to erect idols. It reminds us that our expectations will not be straightforwardly satisfied; we will not get the messiah we think we are waiting for. It emphasizes that God remains beyond our knowledge. It reflects a longing that in some sense remains frustrated and endlessly deferred.

We often think of Advent as a sort of bridge we must traverse in order to arrive at that site of holiness called Christmas. We see Advent as a time when we move ever nearer to the presence of God; the direction of movement is from us to God. But this view gets it exactly the wrong way around. It turns the logic of the messianic inside out. The Scriptures suggest that God is not something we reach, even when we do our best to get things right, even when we strive to be our holiest. Rather, the idea of the messianic is that God comes to us—and, in so doing, radically transforms our way of being and thinking. Here Advent names a divine movement that interrupts and reorients us. If it names an expectation, it is of an event that will be explosive and disruptive—and thus profoundly unexpected.

How do we prepare for this kind of Advent?

An Advent like this seems to require a change in how we think about preparation. We often think of preparation as a gradual filling up, a process of addition or accumulation, a progressive unfolding that moves ever forward. Here is a different image of preparation. It is not so much a filling up, as an emptying. It is a matter not of addition, but of subtraction. It is a negative moment more than one that is positive or progressive, because the Messiah comes as much to defy our expectations as to satisfy them.

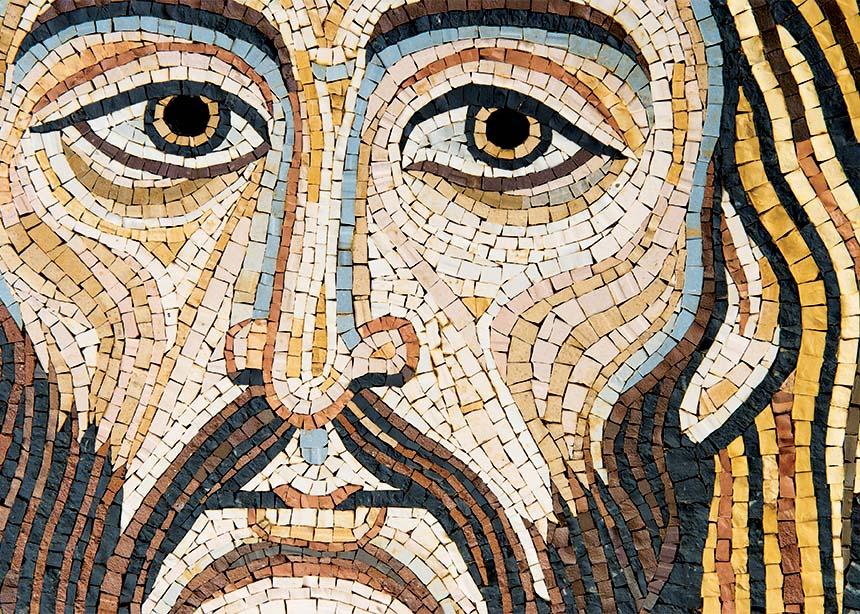

Advent reminds us that we have made Jesus all too familiar. It reorients us to his profound strangeness.

North American Christians tend to approach Advent from the perspective of Christmas. We think that the point of Advent is to focus our gaze on the event of Jesus’ arrival. This is no doubt because our lives are governed so much by metaphors of progress and accumulation. But Advent ceases to be Advent when it is overdetermined by Christmas; the meaning of Advent requires us to turn our gaze the other way around. The peculiarly Jewish character of Advent that we are wont to forget reminds us that we must unlearn the Jesus we think we know so that Jesus can come to us as Messiah.

The season of Advent has as much to do with the Second Coming of Jesus as with his birth in Bethlehem. Let us reimagine Advent as a kind of self-emptying, a hollowing out, so that we can become ready to receive the gift that Christmas has to give—the unexpected gift of a Messiah who comes to save us from the temptation that we must somehow save ourselves.

Chris K. Huebner is associate professor of theology and philosophy at Canadian Mennonite University, Winnipeg. This is adapted from a sermon by the same name, published in Vision: A Journal for Church Theology 12, no. 1 (2011) and is used with permission of the Institute of Mennonite Studies. The sermon is reprinted in Huebner’s book Suffering the Truth: Occasional Sermons and Reflections, published by CMU Press.

For discussion

1. What images or activities do you associate with Advent? What is the Christian church waiting for in this season? When it comes to remembering the life of Jesus, how helpful do you find the annual church calendar (Christmas, Easter, Advent)? Do you think there is danger in having annual rituals becoming too tame and predictable?

2. Chris K. Huebner writes that we think we want a messiah who seems well-known and familiar. Do you agree? How is Immanuel or the baby Jesus portrayed in Advent and Christmas songs?

3. Huebner writes, “Advent brings us face to face with our insatiable desire to erect idols,” and “we will not get the messiah we think we are waiting for.” Why is it dangerous to expect a messiah we think we have figured out? What does it mean for God to be beyond our knowledge?

4. “God arrives in ways we do not expect,” says Huebner. Do you agree? Can you think of times when God did unexpected things in your life? When Jesus began his ministry, what are some unexpected things he did?

5. What will it mean for you to wait for God this Advent season?

—By Barb Draper

Comments

I will reread and study this article by Chris Huebner. I will also share it with others to consider. I have been drawn to the perspective given in this rethink of Advent, and it will shape my perspective. Thank you, Chris.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.