There's a global recession and Canada's economy is not immune.

Shiploads of strange, foreign refugees — economic migrants and oppressed minorities — have been landing on our shores, fleeing civil war, economic upheaval and famine.

No one is certain how they can be assimilated and there are concerns about criminals, subversives and agitators in their midst.

"If (their) ... government is threatening to deport them ... it is probably because they refuse to obey the laws of the country, and we should have full information regarding the facts," one mainstream advocacy group objects.

No, it is not 2010. The year is 1929. The migrants are Mennonites fleeing Joseph Stalin's Soviet Russia and deportation to certain starvation in Siberia. Canada's doors are slamming shut to refugees.

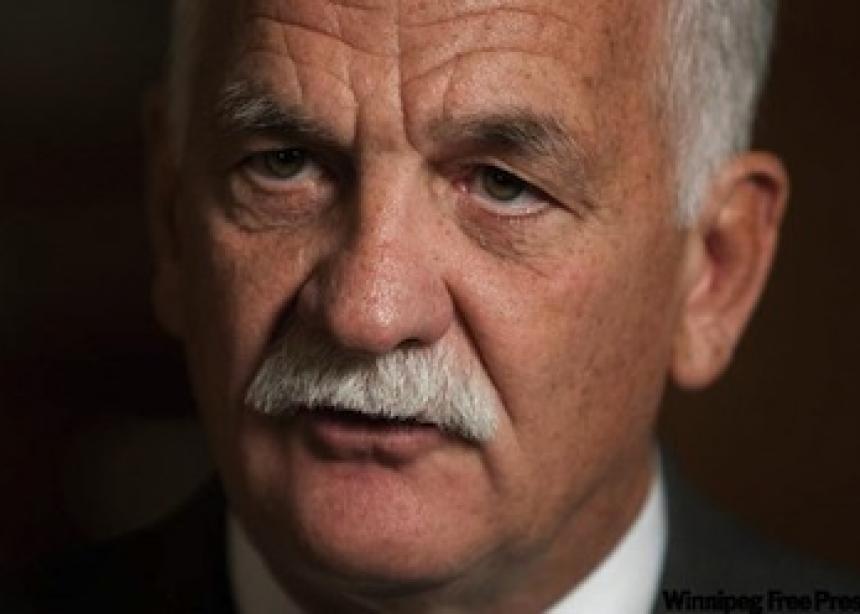

Among the massive Mennonite influx who had helped fuel that public and political backlash were the Ukrainian refugee grandparents and parents of current Public Safety Minister Vic Toews.

While the parallels are not exact, many of the arguments heard today from Toews and others about putting a stop to the mass migration of Tamil refugees to Canada were offered during the 1920s against other targets.

"We are very concerned that there are elements of the LTTE and the Tamil Tigers on board this vessel," Toews said in August, as a ship laden with almost 500 Tamils landed in B.C.

These "suspected human smugglers and terrorists did not come to Canada by accident," Toews said, but targeted Canada due to its history and reputation of accepting migrants.

"This particular situation we believe to be a part of a larger human smuggling and human trafficking enterprise. I don't view this as an isolated, independent act."

Toews' comments quickly made it on to the racist website Stormfront, where a commenter suggested that Canada's government: "Send the ship and all the scum that is aboard it to the bottom of the ocean."

The Public Safety minister did not respond to an interview request on his family history, but would surely view such racial hatred and cold-hearted absolutism with horror.

After all, the Ku Klux Klan of Kanada suggested in the late 1920s that Canada, faced with an influx of Ukrainian Mennonite refugees, "see that the slag and scum that refuse to become 100-per-cent Canadian citizens is skimmed off and thrown away."

And for Toews, such talk should be deeply personal.

His parents, young Anne Peters and Victor Toews, were among the lucky ones who got into Canada before the doors slammed.

Anne arrived with her family as a five-year-old in 1924, among more than 5,000 refugees in the first big year of Russian immigration after Mackenzie King's Liberals opened Canada to eastern Europe's fleeing Mennonites.

Victor's family arrived in 1926 when he was eight, part of the single largest annual migration that topped 5,900 Mennonite refugees.

A year later, only 847 were permitted into Canada and by 1930 — when the need for escape from Russia was most desperate — Canada had closed the door.

"It's a unique period of time, it's a small window," Hans Werner, a professor of Mennonite studies at the University of Winnipeg, says of the short period in the mid 1920s when Anne and Victor arrived in Canada.

"It was entirely legal. Not uncontroversial possibly, but certainly legal. They negotiated an arrangement."

Human smugglers, the current Public Safety minister will be relieved to know, were not involved in his parents' passage to Canada. It was the Canadian Pacific Railway and its steamships which extended credit for the refugee travellers under terms the impoverished Mennonite refugees couldn't possibly meet.

"Where people are moving, there's money to be made," Ed Wiebe, the refugee program co-ordinator at the Mennonite Central Committee Canada in Winnipeg, said in an interview.

He ruefully notes that every Canadian Mennonite child has grown up hearing about the "Reiseschuld", or travel debt, to the CPR.

"Obviously that money is going somewhere," said Wiebe. "Exactly who does the benefiting from such journeys — whether they are inflated CPR prices or middlemen along the way that smooth the wheels for visas — well, gee whiz, if you're stuck you have to trust somebody.

"Smuggling still isn't trafficking, though, and it's unfortunate how quickly that distinction is lost."

Two CPR ships were initially sent to Odessa on the Black Sea, each returning in 1923 with more than 1,000 refugees aboard at $140 for each man, woman and child.

"The Canadian government permitted the mass entry of Mennonites without regular individual passports," historian Frank Epp writes in "Mennonite Exodus: The Rescue and Resettlement of the Russian Mennonites since the Communist Revolution."

Frederick Charles Blair, then Canada's assistant deputy minister of immigration, offered to help the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization "in every reasonable way with a view to assisting you in getting the (movement) of settlers" to Canada.

Not incidentally, that same F.C. Blair would prove instrumental a decade later in Canada's decision to turn away the SS St. Louis and her 900-plus Jewish refugees — memorably stating that other ships would likely follow and "the line must be drawn somewhere."

The first group of 121 Mennonite families arrived in Saskatchewan in July 1923, with the men immediately put to work on the harvest and all their wages going to their transportation debt.

More than 21,000 Mennonites came to Canada under these CPR contracts during the 1920s, piling up an accumulated transport debt of more than $1.7 million. It wasn't fully settled until 1946, when Mennonite groups paid off the last of the principal and the CPR — having benefited immeasurably from the cheap labour and agricultural commerce the settlers provided their railway — wrote off about $1.5 million in accrued interest.

"You might say that one person's smuggling is another person's salvation," says Werner, the Mennonite historian.

It's been a recurring theme in Canada's history: Desperate migrants using any means at their disposal to make a stab at a new life for their families in this under-populated land.

Perhaps a generation or two hence, the child of one of the smuggled Tamil youngsters who arrived over the last year will rise to become Canada's immigration or justice minister — a trajectory that all would hail as a sign of Canada's inclusiveness and opportunity.

Comments

Thank you for speaking up.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.