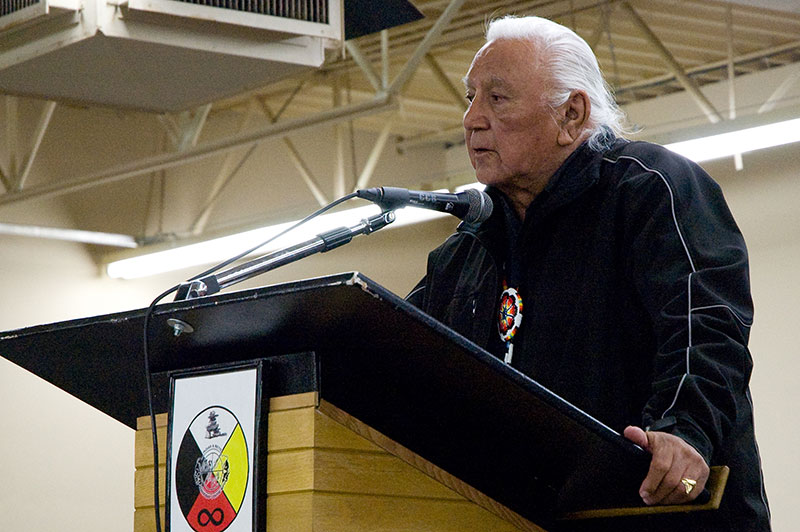

Elmer Courchene introduced himself as an Anishinabe elder whose home is Turtle Island. He carried himself with dignity, but his carefully chosen words reflected the uncertainty within: “I’m 77 years old and, without a word of a lie, I’m still trying to find love.”

When he shared that statement at a healing conference in Winnipeg in June of this year, he was talking about his search for self-identity and belonging. Courchene is an Indian Residential School (IRS) survivor torn from his home and family at the tender age of 7. After 10 years of heart-wrenching trauma in the IRS system, he said, “I wasn’t a human being any more. I was a product.”

Because of his own search for acceptance, he admitted that it was difficult to know how to love his own children and grandchildren.

When the Canadian government co-opted the help of institutional churches to “kill the Indian in the child” by removing them from their homes and families, it accomplished more than it bargained for. At best, thousands of innocents lost the emotional and spiritual foundations essential to personhood. At worst, they endured emotional, physical and sexual abuse. As a result of the IRS experience, generations have been shattered.

“The behaviours we learned at these schools are passed to our kids, even if we don’t intend it,” said Nathan McGillivary, a survivor at the healing conference.

Those remarks address truths that settler folks would rather sweep under the carpet. Let’s move on, we say. Canada has treated indigenous people unjustly, but we offered a public apology in 2008. We made reparations through the IRS Settlement Agreement, including financial support for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) so that stories about our oppression would become part of the public record. Isn’t that enough? Can’t they just get over it?

On the surface, it’s easy to throw blame back at indigenous communities. Bad news abounds: Misuse of public funding, substance abuse, child neglect and welfare dependency. According to a 2010/2011 Statistics Canada report, the indigenous population is over-represented in the Canadian prison system. But without negating individual responsibility for individual actions, it’s important to realize that the circumstances of Canada’s first nation people go deeper than media headlines and finger pointing, and further back than the abhorrent IRS experience and broken treaty promises. It’s far too complicated to comprehend at a glance.

Since the 2008 apology, awareness is on the rise among Canadians, including a growing number of Mennonites. However, the web of tyranny is so pervasive, the consequences so entrenched, that it’s easier to throw our hands up in despair than to untangle the mess.

The TRC process is intended to expose the truth and provide support for survivors, but Canada’s host people say it will not bring closure. So what’s next?

A story from South Africa

Mpho Putu has been on the steering committee of the Anabaptist Network in South Africa (ANiSA) since its inception. ANiSA’s objective is to “walk with, support and grow communities of peace, justice and reconciliation within South Africa.” In Anabaptism, Putu sees hope and guidance for the country as it recovers from apartheid’s ravages. But Putu’s vision was not always so clear.

Putu grew up during apartheid in the black-only township of Soweto. Like other townships, Soweto was structured with separateness in mind. White people lived in the central area—in Soweto’s case, Johannesburg—while those of other races were each assigned to separate designated areas on the outskirts. They were close enough to provide cheap labour for whites, but far enough away that racial paths would seldom cross beyond the workday.

In an e-mail interview, Putu said life for blacks was “determined by other people, white people in particular, through draconian laws that prevented and denied the black majority their human rights.”

Putu was just 13 in June 1976 when the infamous Soweto Uprising captured the world’s attention. Already frustrated with an educational system that deliberately disadvantaged blacks, Putu joined thousands of junior-high and high-school students who rebelled when the government changed the language of study from English to Afrikaans, the language of the oppressor class. For the most part, they marched peacefully, but police reacted swiftly and with force. The first of hundreds to die was a boy about Putu’s age.

Then more adults got involved and police violence escalated. “Our freedom did not just come easy. Blood had to flow, and many died,” Putu said. “Personally I went through what many young people experienced: got beaten, arrested, tear gassed and treated badly by white Christians who confessed Christ as Lord.”

Migrant labour separated generations of fathers from families and local communities, causing widespread emotional, spiritual and physical damage. In a society that never had the opportunity to develop an economy, poverty and vulnerability persist to this day. Violent crime, HIV and other diseases flourish.

“Even when the country is in its 20th year of democracy,” Putu said, “one can see the rampant effect of 300 years of ‘colonialization’ [sic] and apartheid legacy.”

History of legalized oppression

Here in Canada that legacy sounds hauntingly familiar.

Legalized oppression of indigenous people began when church and state operated as one. In the 15th century, Pope Nicholas V instituted the Doctrine of Discovery, giving Christian explorers moral permission to dispossess the original inhabitants of foreign lands. That sense of entitlement was unquestioned by church reformers who came later, and it was imposed on countries around the world by European settlers, including South Africa and Canada.

By 1948, centuries of segregation and even slavery in South Africa evolved into the legal system of apartheid. For almost 50 years, racial division governed everything from housing to public-service access, dramatically favouring the minority settler population.

Andrew Suderman is a Mennonite Church Canada Witness worker in South Africa, and a member of the ANiSA steering committee. In a recent article for MC Canada, he explained that the church determined “the separation of races was not only good, but the desire of God. Although Afrikaners believed they were called to bring God to other races, they viewed those other races as inferior and felt that mixing races would dilute the purity of God’s ‘chosen’ people.”

Like apartheid, Canadian legislation infringed upon indigenous people’s human right to self-determination, and it’s that aspect of history that settler society has trouble grasping. The disturbing details are simply not public knowledge.

The Gradual Civilization Act, an 1857 precursor to the Indian Act, was designed to forcibly assimilate host people into settler society despite its alien worldview. The Gradual Enfranchisement Act followed in 1869, giving the superintendent general of Indian Affairs the right to determine who among host people could own land or were qualified for other benefits. A series of additional legislative measures followed, culminating in the Indian Act.

At various times, the Indian Act prohibited indigenous people from practising centuries-old ceremonies pertinent to their cultural survival and from hiring lawyers to defend their collective grievances. Although the Act has been updated through the years, it continues to exert paternalistic control over the lives of those with “Indian status” and those who live on reserves, including the ways in which they are allowed to draw an income from their land.

In other words, settler society has legislated equality and opportunity out of indigenous people’s grasp.

Ironically, in the late 1970s, while the Indian Act remained a legal document of oppression at home, Canadians expressed horror at apartheid. They joined other nations around the world, implementing economic sanctions against South Africa to pressure the government for reform.

Truth and reconciliation

Both South Africa and Canada established TRCs to publicly acknowledge the vicious legacy of apartheid and IRS, respectively, but the process differs somewhat in each country.

In South Africa, survivors shared their stories and perpetrators of violence were allowed to testify about their role. In exchange, they could request legal amnesty.

Stories told to the Canadian TRC are not considered legal testimony and primarily consist of survivors’ accounts. Despite repeated calls from TRC commissioners for perpetrators to come forward, there has been little response from individuals. Involved churches have offered corporate apologies.

The TRC is not about assigning blame, according to Steve Heinrichs, MC Canada’s director of indigenous relations. “It’s an attempt to encourage settler society to address fractured relationships with host peoples.”

In both Canada and South Africa, financial settlements were made to those who matched certain criteria of abuse. But not everyone who was affected met the criteria and financial settlements are not enough, say indigenous leaders.

“Beyond the settlement, the healing process and spiritual reconciliation is paramount,” said Derek Nepinak, Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, at the June healing conference in Winnipeg.

Challenges to healing

Cobus van Wyngaard, an ANiSA steering committee member, shared some of his views about apartheid via e-mail. He said that, although the legalized racism has ended, it continues in various aspects of South African life.

“An obvious example,” the white Afrikaner said, “would be times when I continued to assume that it was ‘natural’ for black and white people to continue to worship separately.” But he also pointed to racism embedded in architecture and community planning. The townships continue to grow as more black people move closer to the city, he said, while gated communities for whites grow, increasing separation.

The economy is also a challenge. Various economic pressures, and perhaps even bribery, affected the outcome of negotiations leading up to apartheid’s demise, van Wyngaard said. Property rights were enshrined in the new constitution without adequately dealing with the history of unjust property distribution. The settlement debate was complex, he said, “and many would say that the global economic situation of the early 1990s left the ANC [African National Congress] with little choice. Choosing a hard-line socialist agenda right after the fall of the U.S.S.R. would have resulted in extreme poverty.”

“Indigenous peoples across Canada continue to face a grave human rights crisis,” according to a December 2012 Amnesty International report citing access to housing, healthcare, education and water as serious issues.

A June 2013 study released by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives reported that poverty among Métis, Inuit and non-status first nation children averages 27 percent, while half of first nation children live below the poverty line. For all other children in the country, the poverty rate sits at about 15 percent.

In a telephone interview, Norman Meade, a Métis elder and the recently retired coordinator of the Mennonite Central Committee Manitoba Aboriginal Neighbours program, said the Indian Act was designed as “an act of coercion that kept them [indigenous people] dependent upon the central government in Ottawa.”

“Some of the leaders say the Indian Act would be better abolished,” Meade added, “but if you’re going to abolish legislation that’s been in place for a long time, you have to have some kind of relationship between the government in Ottawa and first nations’ governments in communities.”

The relationship between the Crown and indigenous communities is complicated by ongoing treaty concerns regarding compensation to host peoples for settler use of their land and resources. Change, Meade said, must take place through a gradual, defined process that honours the relationship that treaty agreements were meant to establish.

Differing worldviews also create complications. While indigenous people typically consider humans to be one thread in the web of creation for which they assume responsibility, the European/settler view is more apt to see humans as central, holding dominion over the rest of creation. The indigenous perspective places high importance on relationships with creation and other people, while the alternative view tends to place higher priority on economics and development.

A view of transformation

Carl Brook, a white Baptist pastor and the director of the Crusade for Christ organization in South Africa, served in the military during apartheid. He has struggled not only with his role in apartheid, but with his church’s theological justification of it. He first began to question his beliefs about apartheid when he couldn’t see the Christian vision of an alternative society in the church around him.

In e-mail correspondence, he spoke of his “conversion experience” as the only white student in his year at the Evangelical Bible Seminary in Pietermaritzburg. “Three years in a crucible of learning where community was key led me to profoundly re-evaluate my worldview, my ideas of truth and falsehood.”

Brook, an ANiSA pilgrim, said, “It has been remarked that hindsight is an exact science, ‘20/20’ vision. Looking back, it’s easy to see the heresy. But we grow up perceiving and accepting what parents, teachers and society consciously and unconsciously want us to see. Apartheid was endorsed by most white South Africans out of blind ignorance and stark fear. Authority structures feed on and reinforce such emotions to entrench hegemony.”

Where do we go from here?

Isn’t that essentially what happened in Canada?

Mennonites cannot claim total innocence in the history of oppression. Individuals and churches in and beyond MC Canada have been involved with indigenous schools. Like other immigrants, Mennonites benefited from a colonial system that bestowed them with land seized from indigenous peoples. However, as awareness rises, so does Mennonite involvement with the TRC process and other Mennonite-based ministries that are building bridges between settler and host communities.

Those bridges are key to building relationships, and we can’t move forward unless we move forward together.

In his book No Future Without Forgiveness, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, chair of South Africa’s TRC, compares South Africa’s struggle to a scene from the 1958 movie, The Defiant Ones. Two escaped convicts who are manacled together—one black, the other white—attempt to climb out of a slippery ditch. One makes it to the top, but falls back because he is bound to his mate. They can only climb out together. “So, too, I would say we South Africans will survive and prevail only together, black and white . . . as we strive to claw our way out of the morass that was apartheid racism. . . . God had bound us, manacled together.”

A similar approach is also imperative in Canada, according to Heinrichs. “What I hear from indigenous communities is a desire for radical respect that is often connected to traditional spirituality and culture, land justice and redistribution of wealth,” he said. “It’s going to take a costly, communal effort to cultivate. This is not an indigenous problem. Settlers created the woes in ‘Indian country’ with policies most Canadians are unaware of. We have to understand that this is a justice issue affecting all of us.”

So why can’t they just get over it? Because we aren’t yet clawing our way out of the morass together.

Deborah Froese is MC Canada’s director of news services in Winnipeg.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.