American Mennonite conscientious objectors (COs) working in mental hospitals during World War II decried the deplorable and inhumane treatment of patients. One symbolically powerful way they objected—and advocated for better treatment—was to unshackle the patients, collect the iron chains and cuffs, and melt them down into one enormous bell.

That bell, which states, “Cast from the shackles which bound them, this bell shall ring out hope for the mentally ill and victory over mental illness,” now serves as the logo for Mental Health America.

Canadian Mennonite COs who served in mental hospitals during the same war also played a role in reforming mental health care in Canada. Their experiences led to the eventual establishment of the Eden Mental Health Centre in Winkler, Man. Nearly 100 COs in Manitoba served in hospitals, most of them mental health institutions.

The Alternative Service website states, “For the COs who served in mental hospitals during the Second World War, the experience opened their eyes to a world they could never have imagined.”

After the war ended the COs who served in the mental hospitals moved on to other jobs, but the need for improved mental health services remained. Some of the COs had seen things which disturbed them and which they knew should be improved. It was as they related these experiences to the wider Mennonite community that churches became inspired to build Eden, which eventually opened in 1967.

Symposium sheds light on Mennonites and mental health

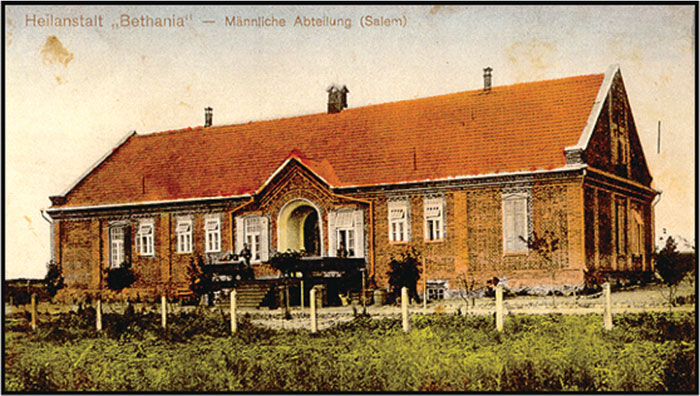

Mennonites in Russia in the early 1900s were concerned about the needs of those in their midst suffering from mental illnesses, feeling they had been neglected for too long. In 1910, they built Bethania Mental Hospital, “the first and only mental health institute established by Mennonites in Russia, and even all of Europe,” noted Ken Reddig, director of the Eden Foundation, at the Mennonites, Melancholy and Mental Health Conference at the University of Winnipeg, Man., last fall, as he presented a paper written by Helmut Huebert.

Responsibility for the development of the institution in what is now Ukraine was handed over to the General Conference Mennonite churches; it was financed by donations and special offerings in the churches twice a year.

People of all faiths were admitted, but Mennonites were given preference. The doctors worked in conjunction with the principles of the Mennonite faith and with Mennonite church leaders. “There were strict orders never to strike a patient or to lock them in individual cells. Occupational therapy in the bakery, garden and farm was offered. Some schooling was provided,” Huebert’s paper stated.

World War I interrupted the development of Bethania and in 1927 the government closed it to make way for the development of a power dam. Until its closure, Bethania offered care for nearly a thousand patients. The Mennonites tried to persuade the government to transfer Bethania to Halbstadt, where there was a medical school, but this did not happen. It was with heavy hearts that they saw the facility disappear.

William Klassen looked further back into Mennonite history as it relates to mental illness. “The early Anabaptist leader, Pilgram Marpeck, knew the problem of melancholia was very real among his people in his time [the 16th century],” Klassen said. “He saw the one primary role of the church as that of a hospital in which people bring their illnesses. The most important thing the church gives to people is forgiveness and joy.” This was in direct contrast to the wider society at that time, he said, which persecuted “witches” and the “possessed.”

Ellen Paulley, a University of Winnipeg student, shared some of her research on “Mental illness in the MB Herald, Canadian Mennonite and Mennonite Mirror.” She noted that over five decades the portrayal of mental illness moved from spiritual categories like “unconfessed sin” to an increasingly holistic approach that includes biological and emotional factors, as well as spiritual.

But John D. Friesen of the University of British Columbia, stated in his presentation that Mennonites “in general . . . have done little to articulate an understanding of the relationship between faith and mental illness. . . . The question of the intersection between faith and depression continues to haunt us.”

“The rift between social/psychological/spiritual explanations and biomedical explanations is beginning to be addressed with more integrative understandings,” he said, but this road towards a more holistic approach has been slow to develop in the Mennonite setting. “I well recall several experiences in the 1980s when addressing Christian pastors and Christian leaders on the psychological underpinnings of addictions, several pastors challenged my psychological perspectives and considered my viewpoints lacking biblical foundations.”

Today mental illness is reported with increasing frequency. “Depression is as much as 10 times more common than it was two generations ago,” Friesen told the conference. Quoting from Great West Life statistics, he said, “Mental health claims [especially depression and anxiety] have taken over cardiovascular disease as the fastest growing category of disability costs in Canada. It is estimated that 10 percent of the Canadian working population has a diagnosable mental illness. The Canadian economy loses an estimated $30 billion a year in productivity due to mental illness and addiction problems.”

Nobody is immune. Mental illness affects people in all occupations, educational and income levels, and cultures. Chris Summerville of the Manitoba Schizophrenic Society said, “Approximately 20 percent of individuals will experience a mental illness during their lifetime, and the remaining 80 percent will be affected by an illness in family members, friends or colleagues.

. . . Receiving and complying with effective treatment and having the security of a string of supports, adequate housing and educational opportunities are essential elements in minimizing the impact of mental illness,” said Summerville.

The situation today

The compassion of Mennonites for the mentally ill is evident in their history, but stigmas and difficulties around mental illness still abound.

Ingrid Peters Fransen, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder after years of misdiagnoses and a smorgasbord of treatments, has on occasion shared her story with her congregation. “What I would like is a response from the church during the week, not just after church,” she says. “I didn’t share all the time, but when I shared it was when I wasn’t in a good place. Sometimes people offered to bring a meal, but it would have been more helpful to be invited over for a meal. I didn’t want to explain that my house was in complete chaos.”

Peters Fransen, whose story is featured in the Mennonite Publishing Network’s Close to Home pamphlet series, can understand the hesitation to become involved. “You don’t know how long someone will not be able to function,” she says. “It would have been easy for me at times to latch on to someone. But a pastoral visit or a phone call every time I shared, that would have been helpful.”

It is not helpful being told, “We all feel depressed sometimes,” she says, adding, “ ‘Pull up your socks,’ ‘There’s nothing wrong in your life,’ and, ‘What is your problem?’ ” are all comments someone with a mental illness doesn’t need to hear. “You’ve already said them to yourself. You don’t need others to say them to you as well.”

Peters Fransen continually strives to erase the stigma of mental illness. “I use physical illness as a marker,” she says. “If I were chronically physically sick, it isn’t the first thing I would talk about, but if it comes up in a conversation I would address it. So it is with my mental illness.”

Lois Edmund, a psychologist and instructor at Canadian Mennonite University, Winnipeg, says the church is called to be compassionate and welcoming to all. “The sad part is, if we are not compassionate, people will go elsewhere, like turning to alcohol, for example, for help. People with mental illness sometimes feel cut off from friends, family and church, and, as a result, from God. The church needs to be compassionate in its response and let them know that God has not turned his back on them.”

Edmund sees a need for the training of leaders and others in the church in understanding and learning how to respond to mental illness. “As churches, we need to become informed,” she says. “It is crucial.”

Carman Mennonite Church congregants felt the need to build that awareness and understanding in themselves last fall. Recognizing that everyone suffers from some level of mental strain and illness at some point in their lives, the congregation wanted to learn how they could be more accepting and supportive of each other. A four-part adult Sunday school series was offered, covering a range of topics, from depression and abuse, to addictions, stress and anxiety. Professionals were brought in to address these issues from a faith-based perspective. Attendance mushroomed during these sessions. A support group has grown out of the series.

“It was refreshing to be able to have these discussions in a church setting and not have to talk in hushed tones,” says a participant.

“What Carman Mennonite did is a very good model of how to ease some of the stigma and pave the way for more understanding,” says the Eden Foundation’s Ken Reddig. “I hope we can replicate that in other churches.”

At Pinawa Christian Fellowship, the multi-denominational congregation in rural Manitoba has decided to forego building a church structure on land that it has owned for more than two decades. Instead, it will continue to meet in the school and use the land to build housing for people struggling with mental illness.

“There is very little available in the way of housing that is accessible and appropriate for them in rural areas,” says Pastor Robert Murray. This congregation, which belongs to the Anglican, United and Presbyterian churches, as well as Mennonite Church Manitoba, is in the process of submitting an application to Manitoba Housing. The plan includes a two-storey, 12-unit apartment building in which half the units will be reserved for people who qualify for the housing supplement. “We learned from Eden Mental Health Services that it is preferable to have a mixed population in these settings,” Murray explains.

The church invited Summerville from the provincial schizophrenic society to speak at a worship service and at a larger community event. “We need to build awareness in order to develop acceptance and support of the idea in the community,” says Murray. “We put an article in the local paper. So far, the response has been very positive.”

The plans also include a common space, as well as storage and office space. “There is a real dearth of space in our community for support groups to meet,” Murray says. “Hopefully, the church will be able to have a role in providing social outlets and connections, so the people won’t feel isolated.”

Dr. Michael Dyck, psychiatrist at the Eden Mental Health Centre, sees an encouraging shift in how the church is responding to mental illness. “In the past, the church saw its role through the institution,” he says. “Their involvement was through the board and by referring people with mental health issues to Eden. Increasingly the church is now asking how these individuals can become a part of the life of the congregation.

“In the 1960s the church had to make the case for the need of an institution to the government,” Dyck says. “Now the church is asking what the role of the community is in recovery and in including them in the church.”

For discussion

1. What experiences have you had with friends or family members who struggle with poor mental health? What resources or support services are available in your community? Has your attitude towards mental illness changed over the years?

2. John Friesen reports that depression is 10 times more common than it was two generations ago. Do you find that surprising? What factors may be leading to a higher rate of diagnosis? How healthy is this high level of diagnosis?

3. What is the relationship between faith and depression or anxiety? Do these disorders show a lack of faith or are they merely biological disorders? What role can a pastor or church play in mental health issues? What are the advantages of having faith-based community counselling services?

4. What are the challenges in dealing with friends or family members who struggle with mental illness? How could your congregation improve its support for members who suffer from mental health issues?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.