Munther Isaac recently published a book that confronts a longstanding problem in Christian attitudes toward the Holy Land—ignorance, indifference and even hostility to the Palestinian church. Isaac is an Oxford-educated, Palestinian Lutheran pastor who serves as academic dean of Bethlehem Bible College.

“When it comes to western Christian attitudes towards Israel,” Munther writes in his book, The Other Side of the Wall: A Palestinian Christian Narrative of Lament and Hope, “one of the most troubling is the attitude toward Palestinians and Palestinian Christians. [Those attitudes] range from ignoring Palestinians completely, to discrediting our experience and existence, to crushing and dehumanizing us.”

The fact that Munther’s book was published by the evangelical InterVarsity Press indicates an openness among Christians outside the region to listen to Palestinian perspectives. A new generation of Palestinian scholars and leaders like Isaac are reaching international audiences with their challenging biblical vision about land and justice.

To learn from Christian brothers and sisters in the occupied territories of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza often means shedding media-driven stereotypes of Palestinians (contrary to stereotype, most Palestinians do not support terrorism), and church-driven idealization of Israelis as the covenant people of God (in truth, the State of Israel is secular and is often accused of human-rights abuses).

Mennonite connections in the region date back 73 years. And Mennonite Church Canada established a formal relationship with the college in 2020.

Change of heart

When Beverley Timgren of Toronto first started her missionary career in the 1980s, she was steeped in a common view of Israel’s 1948 military conquest of the region as a miracle, proof that God was on Israel’s side—a heralding of the imminent Second Coming of Christ.

That perspective became increasingly problematic as her assignments took her from dentistry work in southern Lebanon and northern Israel to the West Bank, where she has worked several stints as an English teacher at Bethlehem Bible College.

“Through living there and getting to know Palestinian Christians, I ended up seeing through very different eyes,” she says.

What Timgren saw was people who showed “amazing hospitality” and who aimed “to live at peace and in equal dignity with their Israeli neighbours.” Their faith and resilience are remarkable, she says, given the challenges they experience under the decades-long military occupation by Israel—confiscation of more and more West Bank land for Jewish Israeli settlements, tight restrictions on movement through a network of barriers and checkpoints, and the thwarting of their dreams of self-determination.

Today, Timgren serves on the board of Hope Outreach of Canada, a ministry partner of the college.

Holy Land remnant

Bethlehem Bible College was established in 1979 by Bishara Awad, who had been principal of a school supported by Mennonite Central Committee in nearby Beit Jala. His vision was to train Arabic-speaking leaders for ministry in their own land—and to help stem the flow of emigration to the West. The shrinking of the Christian population, due largely to the harsh realities of the occupation, was—and continues to be—a major worry of the churches in the region.

Christians of all stripes number less than two percent of the population in both Israel and Palestine, down from about eight percent at the formation of Israel in 1948.

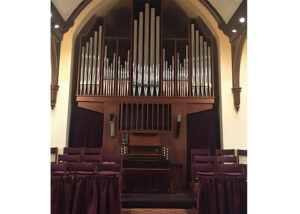

While relatively few Christians now live in the Holy Land, many visit. The college is one of the essential stops for any Christian who wants to get behind the news headlines and meet “the living stones” of the land. The college is within walking distance of the West Bank’s most famous landmark, the Church of the Nativity, and is just 500 metres inside the massive concrete wall that isolates the occupied West Bank from Israel proper.

On the other side of the wall, about 10 kilometres to the north, is Jerusalem’s Old City.

Over time, the college has developed a faculty of Palestinian church leaders and teachers whose core focus is biblical studies. Local enrolment is about 60 students. Even before the pandemic, however, the college had added online courses to its regular offerings in biblical studies and leadership, raising the total enrolment to more than a hundred.

Building peace

Bethlehem Bible College has also helped spawn other ministries of witness and compassion that allow visitors and volunteers from around the world—including several from MC Canada—to engage believers in the region:

- In spring, many students travel to Jordan to share their faith and humanitarian assistance with refugees from other Middle Eastern countries.

- The college’s Shepherd Society offers social assistance to community members experiencing health crises and poverty. The school also offers job training for media workers and tour guides.

- Every Christmas, the college puts on an outreach banquet for the community.

- The college’s latest innovation is the Bethlehem Institute of Peace and Justice, an English-language program that helps Palestinian and international students consider biblical perspectives on peace and justice from within the context of the Holy Land. Through an arrangement with St. Stephen’s University, based in New Brunswick, the program’s courses can be taken for university credit recognized in North America.

In many ways, these initiatives reflect best practices for mission work—international Christians partnering with local believers to extend their witness. It’s the spectrum of theological and political views around Israel, however, that make the relationship between Palestinian believers and their foreign counterparts delicate.

Christ at the Checkpoint

Jack Sara, Bethlehem Bible College’s president, and a Christian and Missionary Alliance pastor, walks a fine line between upholding Christian witness and confronting opposition. The opposition is not primarily from Muslims in the region, but from fellow Christians abroad—whether evangelical or historic mainline groups—who uncritically support the State of Israel.

When Sara attends mission conferences in North America, he expects to be targeted. “I am pushed hard, because of the [college’s] name, and because I don’t go with the Christian Zionism track,” he says. He has colleagues who have been uninvited from conferences that decided Palestinian speakers might be controversial.

Since 2010, the college has hosted the biennial Christ at the Checkpoint conference, which has brought together hundreds of participants and speakers from around the world to take a biblical look at issues such as terrorism and religious radicalism. Even though it features a stimulating spectrum of voices, including Messianic Jews, the gathering attracts criticism from the Israeli government and Christian organizations that support it.

The first conference was held a year after a significant statement was released by Kairos Palestine, a consortium of Christian leaders in the region. “A Moment of Truth: A Cry of Hope from the Heart of Palestinian Suffering” calls Christians to advocate for a just peace in the land. Rooted in Scripture, it endorses nonviolent resistance to the occupation, using a “logic of love” for Israeli Jews, Palestinian Muslims and Christians alike.

Mennonite engagement

The statement was a key impetus for a 2016 resolution on Palestine and Israel passed by MC Canada. Rooted in decades of Mennonite partnerships with Palestinians and Israelis in humanitarian and peace work, the resolution called for prayer, education and political advocacy in partnership with Palestinian and Jewish Canadians.

“We don’t see the New Testament as devotional reading only,” says Jeanette Hanson, director of International Witness for MC Canada, which stewards the partnership with the college. “It profoundly engages culture and politics.”

With the blessing of the denomination, the Palestine-Israel Network (PIN) came together in the months following the 2016 resolution, drawing together individuals and working groups across Canada.

With the resolution as their mandate, PIN members have led workshops, organized webinars, written to politicians, met with MPs, and disseminated prayer requests for church bulletins.

The MC Canada partnership with Bethlehem Bible College (BBC) envisions educational exchanges and deepening relationships between Palestinian Christians and Canadian Mennonites.

To fulfil that mandate, Hanson is working with regional church PIN groups, church leaders and schools to mount a series of four speaking tours featuring college faculty in Manitoba, Alberta, Ontario and British Columbia. The first of these took place in Manitoba this past fall.

The BBC-MC Canada partnership also envisions MC Canada volunteers doing short-term service stints at the college.

In this work, MC Canada is joining a growing number of Christians world-wide, who are taking up the challenge of Munther Isaac and other Palestinian Christians. That challenge is to listen carefully to the stories of suffering and hope coming from the Holy Land today, and to come alongside brothers and sisters in Christ who are working for peace that is married to justice and mercy.

Byron Rempel-Burkholder is chair of the MC Canada Palestine-Israel Network. He lives in Winnipeg. A version of this article first appeared in Faith Today. Reprinted with permission.

For more, visit bethbc.edu and mennonitechurch.ca/pin.

For discussion

1. When you think of Bethlehem, what is the image that comes to mind? If you visited the Church of the Nativity, how do you think you would respond to this landmark that is believed to be the spot where Jesus was born?

2. The article says Christian attitudes toward the Palestinian church include “ignorance, indifference and even hostility;” what have you been taught about Palestinian Christians? Why have many western Christians been reluctant to embrace the Palestinian church?

3. The purpose of Bethlehem Bible College is to train Arabic-speaking leaders for ministry, hoping to reduce the rate of Christian emigration. Why has the Christian population in Palestine declined so drastically? In what ways is Bethlehem Bible College a sign of hope for the Palestinian church?

4. Do you think Mennonite churches see God as being on Israel’s side?

5. How does Bethlehem Bible College represent hope for the Christian church?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.