The disciples were shocked when Jesus said, “One of you will betray me.” Judas’s story is told in different ways in the gospels, giving us some insight into how the disciples and gospel writers came to terms with the betrayal of Judas.

In John’s gospel, Judas is mentioned five times, and every single time the writer mentions that Judas is the one who betrayed Jesus. This gospel writer tells us that Satan “entered into” Judas (John 13:27). And we are told that when the woman pours the ointment on Jesus’ feet, it is Judas who says this could have been sold for 300 denarii. John’s gospel names Judas as a thief who only wanted the money for himself.

In Matthew’s gospel, we hear the same story of the woman pouring the ointment, but Matthew doesn’t single out Judas as objecting to the act. Matthew recounts that all the disciples said it was wasteful to use the ointment. Matthew does not name Judas as a thief. I wonder about this.

Perhaps Matthew, as a former tax collector, had some personal understanding of Judas’s love of money. He decided not to name that in his story.

Matthew also adds a few important details to the story of Judas. Matthew remembers that in the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus calls Judas “friend.” Significantly, Matthew also tells us that, before Judas died, he repented of betraying Jesus and gave back the 30 pieces of silver (Matthew 27:3–6).

John’s gospel does not include that story, although he must have known it.

What’s happening here? Matthew and John were both equally affected by the betrayal of Judas, but Matthew paints a kinder picture. He says Judas betrayed Jesus, but he tells the story in a more merciful way than John’s gospel. Neither gospel suggests that Judas be forgiven for his betrayal, but I think Matthew was taking some steps along that road.

Communion table

Evan, a member in one of the churches I pastored, was arrested after being caught sexually abusing a boy in our neighbourhood. Evan was released on bail awaiting trial; his only restriction was not being near the boy he abused. Evan wanted to attend our church, and we worked on how that could happen safely. He was always accompanied by a volunteer who never left his side.

The first time Evan was in church after his arrest, it was communion Sunday. I was officiating. As people came up to gather in groups around the altar table for communion, I saw Evan at the back, and I thought, “Don’t come up for communion! Don’t come!”

But sure enough, Evan came up for communion. I found myself having a fierce conversation in my head with God about whether I should serve this man. I stormed inwardly, “God, he doesn’t deserve to be here!”

When I heard myself saying those words in my head, it was like something very heavy dropped on my foot. I could not ignore what I said—it was sharp and painful. Deserve communion? Who among us deserves to be at this table?

My deepest presuppositions about the communion table were suddenly revealed. Somehow, I felt I deserved to have the Lord’s Supper because I did good things. Evan had done bad things, and I didn’t think he qualified. This realization came to me in a flash, and I knew my thinking was wrong and needed to change.

We are loved simply because we are God’s children. We don’t earn God’s love.

At the Last Supper, Jesus broke bread and served all his disciples with love, even though he knew that Judas would betray him, and Peter would deny him. The communion table in our church belongs to Jesus, and not to us. As Evan stood in the circle waiting to be served, I prayed that God would give me grace to grow into the ministerial shoes I was wearing. I came away from the communion table changed, unburdened of a theology that was distorted and corrupting.

The following months were challenging. Our church accompanied Evan to court, where we listened to the testimony of the boy he abused. The boy and his parents sat on one side of the courtroom with friends and supporters, and we sat on the other. I had a son at home the same age as this boy who was testifying. I wanted so badly to be on the boy’s side of the courtroom. But I knew that, as Evan’s pastor, I was called to support him.

We spoke with the boy’s family, who had known Evan from the time he was young. This family knew we had deep feelings of support for their son, but they wanted Evan to have some support too.

Evan eventually pled guilty and received a suspended sentence. A few months later, he died of a heart attack.

At his funeral, someone from our congregation said, “We tried to support Evan. We didn’t do that perfectly, but he knew we were trying.”

Those events took place 20 years ago, and I am still unpacking what happened over those months. I have slowly found the words to tell that story and what it means to me.

Like the writers of the gospel of Matthew and John, we can choose how to tell our stories. When you think back to conflicts and hurts in your life, how do you explain what happened? Telling our stories through the lens of the Last Supper, we can see more clearly what needs to be seen.

Prayer:

With basins and bread and wine that night,

you told your story of love.

We are still listening,

still trying to absorb the meaning.

As we tell our own stories of betrayal,

tales of disappointment and heartache,

we want to follow your example.

Jesus, lover of us all, we want to join you on your knees in the garden. Amen. l

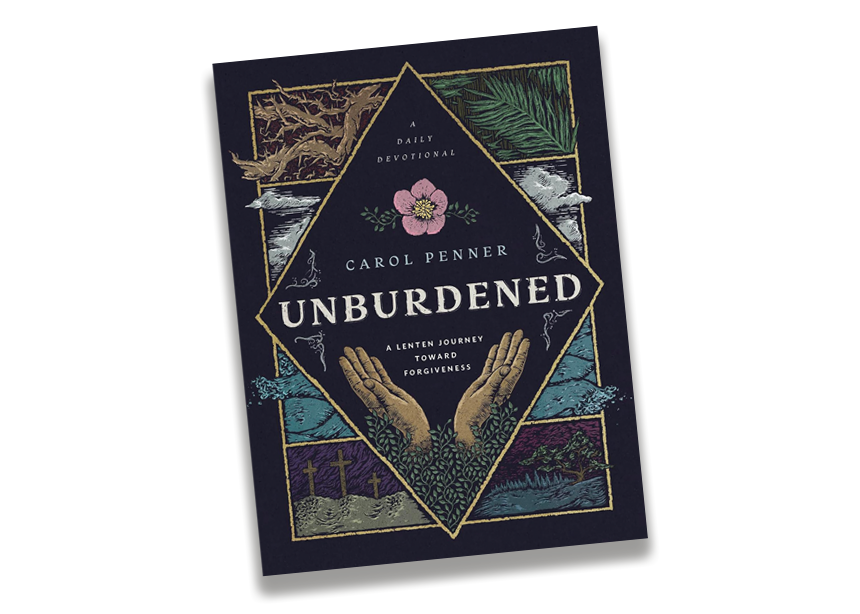

The above is from Unburdened: A Lenten Journey Toward Forgiveness (A Daily Devotional) by Carol Penner. Used and adapted by permission of Herald Press. All rights reserved. Unburdened is available at commonword.ca. To join Carol’s book club discussion of Unburdened during Lent, see facebook.com/groups/1282394419009210

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.