“And when you send a slave out from you a free person, you shall not send him out empty-handed. Provide liberally out of your flock, your threshing floor, and your wine press, thus giving to him some of the bounty with which the Lord your God has blessed you. Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God redeemed you” (Deuteronomy 15:13-15a).

Those Jubilee instructions have an antique ring today. Slavery seems a thing of the distant past. But in fact, it has only gone underground, and exists in modified form even here in Canada, often right under our noses.

“We walk past people who are in bondage all the time and don’t even realize it,” says Christy Langschmidt, a member of Toronto United Mennonite Church (TUMC), who has led the congregation’s project to launch a transitional housing project for survivors of human trafficking, today’s form of enslavement.

When Aurora House opens in a large church-owned house, hopefully this fall, it will be a historic first for Mennonites and the city of Toronto.

Survivors of human trafficking may include Canadians, as well as foreigners brought in through legal channels but on false pretenses––told they had been lined up for good jobs, and then abused, threatened and coerced into doing degrading work for long hours and little or no pay. Some are forced into the sex trade, or underground labour in construction, agriculture, restaurant work, or as domestic help. Typically, they may know little of their rights in Canada, may be intimidated by threats to their family back home, have had their important documents confiscated and have no idea where to turn for help.

Although little noticed here, they are part of an estimated 30 million people around the world who live in some form of bondage.

“These stories are being lived out all around us,” says Langschmidt. “Crops are being picked by slaves, highrises are being built by slaves.” She recalls a case of 60 men recruited in Hungary who, according to the RCMP, had been controlled in Canada by just three people, who took their passports, crammed them into basement apartments and forced them to work without pay, under threat of harm to their families.

In another case, a live-in domestic worker who had toiled without pay for years was tossed out on the street at age 82, when she was too old to carry on.

When traumatized survivors do manage to escape their situations, Canadian cities are woefully ill-equipped to provide them with social, spiritual and economic support. Toronto has no shelter specifically for trafficked people, although a growing network that includes churches, immigration settlement agencies, and even a retired female detective in the sex crimes unit has been drawing attention to the desperate need for designated housing and programs.

The seeds for TUMC’s mission to help these marginalized people were planted unknowingly nearly 20 years ago, when an elderly man approached the church about buying his house. Having recently built a new sanctuary, the congregation wasn’t prepared to commit to such a purchase, but some members pooled their money for a down payment, in faith that someday the building would serve some future missional purpose.

After two decades of being rented out as apartment units––with all shares in the house eventually donated to the church––the house was suddenly empty and in need of a lot of work. The congregation faced a decision: sell it, renovate it to rent again, or finally decide on a new missional project. But what?

Enter Langschmidt, a new attender who had been nurturing seeds in her heart for this project for many years. The daughter of a non-denominational minister who trained others in urban ministry, she had volunteered briefly as a teenager with an organization that helped prostitutes get off the street. It left her with a passion for empowering people who have been exploited.

So when church chair Doug Pritchard made an announcement one Sunday about a congregational meeting, Langschmidt snapped to attention. “That was the first I listened to the fact that the church had a house,” she says.

She’d been reading a book by Christine Caine, founder of the A21 Foundation, a Christian group dedicated to abolishing slavery worldwide, and Half the Sky, about the plight of women in the developing world.

“I read them and had one of the few times in my life when I felt God really grabbing hold of me, almost physically, calling me to give up everything and do this,” she recalls. “I wrestled with it because I realized there is danger in this; the people doing [human trafficking] are sometimes quite organized. And I felt like God was telling me that that was going to be OK, and that I was hearing him loud and clear.”

With her husband’s blessing, Langschmidt stopped working in the family business, began attending conferences, including the first international anti-trafficking summit in Ottawa in 2013, and started looking for ways to use her business skills to help, including building the website of an anti-trafficking network. She made connections with the local Rotary Club, large churches, and other groups who were working on the issue, and learned of their frustrations in developing a local safe house.

A newbie Mennonite, she soon realized TUMC was a church with “a heart for justice issues.” Pastor Marilyn Zehr’s sermon inviting congregants to help discern God’s purpose for the house encouraged her to share her passion with the church’s mission and service committee, and a task force struck to decide what to do about the house as well as to ponder building an addition to the church’s own facilities.

In November 2013, TUMC hosted a “day of awareness” that helped educate members on the issue. As interest grew, a series of “Soup & Sophia” (wisdom) lunches––a TUMC tradition at times of discernment––helped the congregation learn more, with members responding each time to these questions: What do you affirm or are drawn to about this proposal? What do you resist? What suggestions do you have? And: What questions do you still have?

Gradually, anti-human-trafficking work began to seem like a natural extension of the urban church’s 35-year history of refugee sponsorship and work with the homeless. But was it doable? Organizational and financial concerns were a big part of the discernment process.

Those working on the project were stunned and thrilled to learn that the Toronto Mennonite New Life Centre, the refugee settlement agency that co-owns TUMC’s building, had been thinking independently about how it could help trafficking survivors, and was enthusiastic about offering the case management and programming the shelter will need. Sources of financial help were also beginning to appear.

Once the congregation was able to say an enthusiastic yes to the shelter, the hard work of planning, design, working with city authorities, choosing a contractor and fundraising began. A pledge drive at TUMC helped set the scope of the dual projects: the church’s own building addition was scaled down, and a decision was made to thoroughly renovate the house.

“After some years of exploring good uses for this house, the vision for serving the survivors of human trafficking has really caught our imagination,” says Pritchard. “The vote last June to move in this direction passed by 90 percent, and we have pledges for over two-thirds of the capital costs.”

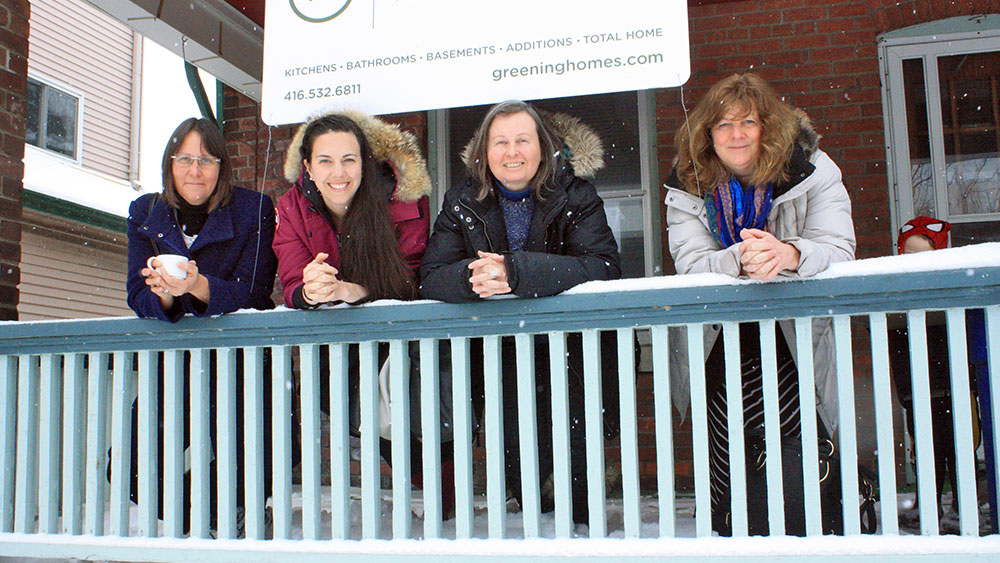

An environmentally-conscious renovation company offered a discount for its services to rehabilitate the large century-old house and create fresh and comfortable living units on three levels. Neighbours were invited to meetings to understand the project better.

The home was christened Aurora House by a congregational vote: a reference to dawn, or perhaps the northern lights––glimmers of beautiful light shining in the lives of those who have lived so long in darkness. Its motto: “Partnering for healing, hope and freedom.”

A separate board, which includes TUMC members as well as community experts, has been formed to direct Aurora House as an incorporated not-for-profit organization, while the building itself remains the church’s property. As work proceeds on the house, an enthusiastic volunteer force is working on fundraising and grants to cover $350,000 for the first year of programming, with government social aid expected to help in paying some of the rental costs.

There is still a long way to go, but with God’s help Aurora House looks forward to becoming, very soon, a warm and welcoming sanctuary for people in desperate need.

A shorter version of this story appeared in the June 8, 2015 print issue of Canadian Mennonite.

To learn more about the project, visit aurorahouse.ca or the project’s Facebook page. For examples of human trafficking, see the video on the Facebook page of International Justice Mission.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.