The first time I flew overseas, I remember wondering whether I had flown beyond the reach of God. We had, quite literally, risen on the wings of the dawn and settled on the far side of the sea. My husband reminded me of Psalm 139: “…even there your hand will guide me.”

I’ve had a similar thought as I’ve travelled to various parts of Canada, only in this case, what astonishes me is thinking about how this place or that place has the same prime minister.

Canada is a big place, yet we all fit, however messily, under a single banner.

We all have the same prime minister, whether we’re fond of that person and their policies or not. God’s hand still guides us on the far sides of the country, geographic and political.

And even across borders.

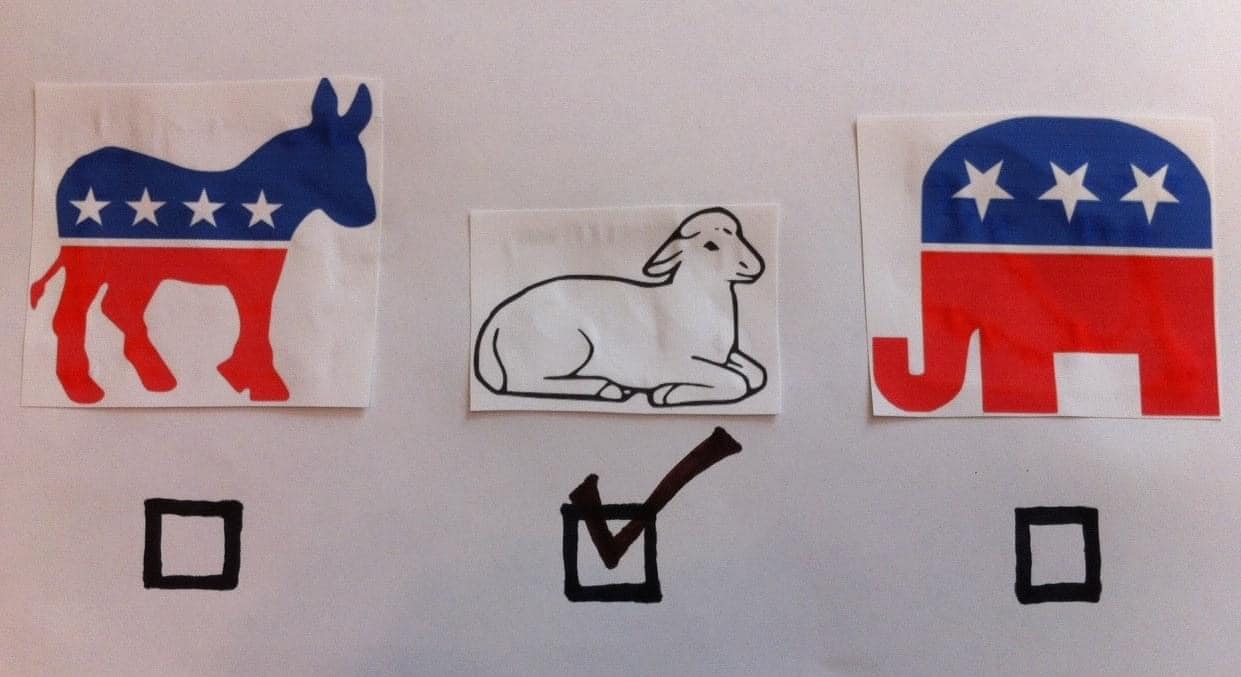

The radio this morning announces that it is a mere eight days until the American election. The world is waiting, knowing this election’s impact goes beyond borders.

I remember walking my dog the morning after the 2016 U.S. election, seeing stunned faces. It felt important to me to greet each one with a smile and a word. It made me think of the movie The Princess Bride, the moment in which the narrator explained, “when he was saying ‘as you wish,’ what he meant was ‘I love you.’”

That’s what I was saying the day after that election, to people I knew and those I didn’t, to those I shared beliefs with and those I presumably didn’t.

Even there, your hand will guide me.

With division in the air, I’m thinking about how we come together when it feels like we (or those we disagree with) are beyond the reach of God. I’m especially thinking about polarization and divisions in the church.

To that question, I really appreciate what Jesse Nickel writes in our latest issue (November 2024[WB1] ) about unity being what defines the church far more than any particular theology.

It’s a big church, the Canadian Mennonite church is, with theological and political diversity that is as different as the Laurentians are from the Rockies, as the tides of Fundy are from the farmland of southern Ontario, as the plains of Abraham are from the prairies of Manitoba.

At the time of the signing of the U.S. constitution in 1787, Benjamin Franklin acknowledged,

“I confess that there are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them. For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that, the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others.”

We could borrow some of that for our big church in our big country.

Later, Franklin offered his famous line about what the United States was: “A republic, if you can keep it.”

The good news is that we don’t need to keep the church—that’s the job of the God who will guide us, whose right hand will hold us fast.

But, as Nickel writes, “When the church recognizes that unity does not mean unanimity, but that we are held together by something—by someone—that transcends any barrier that might stand between us, we have the opportunity to be an embodiment of God’s reconciling power.”

We’re about to witness another divisive American election and we’re likely to face one here at home. But every day in our church, we face issues and ideas where we profoundly disagree.

Are we—or the people we disagree with—beyond the reach of God? Or are we just part of a big church in a big country?

Nickel says, “The church must not succumb to division, hostility, and ‘othering’ within ourselves, for to do so is to reject what Jesus has accomplished through his blood, and to turn our backs on our calling.”

What would it mean if we met the folks we disagreed with in our church and, to paraphrase The Princess Bride again, they were amazed to discover that beneath whatever we are saying, what we mean is, “I love you.”

Too much?

What if we began by remembering that God loves them, and us.

Nickel writes: “In the first half of Ephesians 2, Paul’s attention is on the reconciliation effected by Christ between human beings and God—transformation from death to life—but there is another aspect of this gospel, the focus of Ephesians 2: 11–22, one that many Christians attend to less often. In these verses, the reconciliation takes place between formerly hostile groups of human beings. This is not an add-on to the gospel proclaimed in the first 10 verses of the chapter—it is the gospel.”

As you wish.

LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0geyBtYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAzMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbiB7IGJvdHRvbTogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcik7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDAgMCA1cHggMDsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IHVse2xpc3Qtc3R5bGU6bm9uZTttYXJnaW46MCAwIDEuNWVtIDA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse21hcmdpbjowICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3RvcDowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHtncmlkLXJvdy1lbmQ6dW5zZXQgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6OmJlZm9yZXtjb250ZW50OiIiO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3BhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxsOjptYXJrZXJ7Y29udGVudDoiIn0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgaW1ne2hlaWdodDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7d2lkdGg6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7YWxpZ24tc2VsZjplbmR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczpyZXBlYXQoMTIsIDFmcil9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1jb2xsYWdlIGltZ3toZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MDtncmlkLWF1dG8tcm93czoxcHg7b3BhY2l0eTowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgaW1nLC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpZnJhbWUsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHZpZGVvey1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt3aWR0aDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7ZGlzcGxheTpibG9ja30udGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbntwb3NpdGlvbjphYnNvbHV0ZTtib3R0b206MDt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjYpO3BhZGRpbmc6NXB4IDJweDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtjb2xvcjojMzMzfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uOmVtcHR5e2JhY2tncm91bmQ6dHJhbnNwYXJlbnQgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgZmlndXJle2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IGltZ3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDoxMDAlOy1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjpib3R0b219I2xlZnQtYXJlYSB1bC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5e2xpc3Qtc3R5bGUtdHlwZTpub25lO3BhZGRpbmc6MH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uIHsgYm90dG9tOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHsgcGFkZGluZzogMCAwIDVweCAwOyB9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb24geyBib3R0b206IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgeyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgeyBwYWRkaW5nOiAwIDAgNXB4IDA7IH0gIH0g

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.