After 50 years in ministry I have discovered that there is a significant interplay between the divine and human when it comes to physical and emotional healing. All healing is a work of God’s grace, including medical, psychological and social interventions, whether the caregivers acknowledge it or not.

Looking through the “eyes of faith,’’ all healing, at whatever level, is indeed divine. Having lived with cancer for 20 years, this discovery has existential meaning for me.

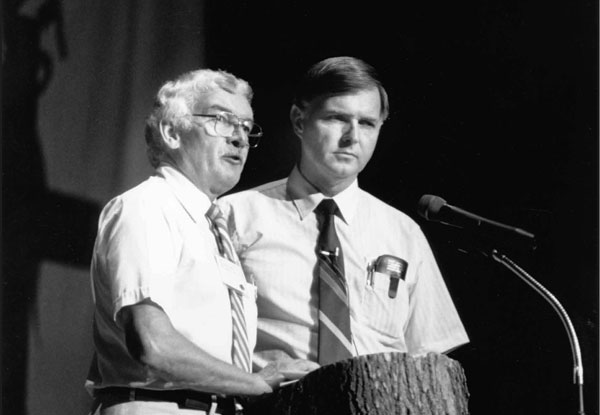

In reflecting on what I have learned, I have to give credit first of all to a Christian lineage of parents and grandparents, who, as farmers, gave me a foundation of honesty and fairness; to evangelists George R. Brunk and Howard Hammer, who not only nudged me to confess Christ but to follow him in a call to service; to a kind bishop in the Amish Conference (later to become the Western Ontario Conference), who instructed me, along with other young teenagers, in the Dortrecht Confession of Faith; and to Eastern Mennonite College, Goshen Biblical Seminary and Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS), that gave this “Amish boy” the educational tools and training for ministry.

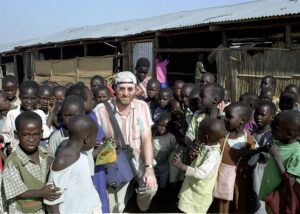

My 50-year journey in ministry began in 1961. Since then, I have served as an urban pastor for 13 years, conference minister for six years, college president for 10 years, and director for conference-based and related off-campus theological education for seven years. For the past 14 years, my retirement involvement has included a variety of volunteer congregational and community ministry projects.

Following, learning

Looking more closely at my “call,” I am reminded of Jesus’ call to his first disciples as recorded in the Gospel of Luke. They were from “fishing” families, so Jesus engaged them in that context. Jesus got into the boat with Simon, asking him to move away from the shore so he could teach the gathered crowds. When he finished teaching, they launched out to do some fishing. The “experienced” Simon protested, suggesting that they had already tried that and it didn’t work. But out of respect for the rabbi, he did as Jesus requested. Then a miracle happened: there were so many fish that the nets began to break.

Simon Peter comes to a new awareness as he falls on his knees, saying, “Go away from me, Lord; I am a sinful man!” Then comes the invitation to Simon, “Don’t be afraid; from now on you will catch men.” The record says that Simon Peter, James and John “pulled up their boats to the shore and left everything and followed him.”

I am convinced that people are called out of their work/home environments to do God’s work in the world. People doing ordinary jobs are called to an extraordinary mission, to engage—catch—people with the message of the gospel. The 12 disciples had a three-year training experience as they followed Jesus while he ministered to people. Perhaps this provides a paradigm for us:

- Repentance: recognizing our sinfulness;

- Following: leaving our former jobs;

- Learning: spending time in preparation for ministry.

Pastoral preparation for ministry

Arriving at Valleyview Mennonite Church, London, Ont., in June 1961, I felt somewhat prepared to assume the role of pastor of an emerging urban Mennonite congregation. Within a month of my arrival, I conducted the funeral of two young girls, members of our Sunday school program, who were burned to death in an apartment fire. At that moment I realized that we had never discussed conducting funerals in our pastoral education courses. For that matter, we had not dealt with how one ministers in other significant rites like baptisms or weddings. I survived that first experience, but that was the first of a variety of times that the limitations of my education came to the fore.

Another experience three years later shook my confidence as a minister, causing me to look for an exit from pastoral ministry. Renting one of our bedrooms to a young man whose family we knew from my home community, and who came to work in the city as the manager of a small shoe store, I became aware that he was struggling with serious emotional issues. I tried to persuade him to seek psychiatric help, but he resisted, saying he was in conversation with a physician as well as a psychology professor.

He went home one weekend, entered the bathroom and drank a lethal dose of rat poison, ending his tortured emotional life. I attended the funeral and also discussed the outcome with his employer, who happened to be a Christian. In the ensuing weeks I was in turmoil as I reviewed what I could have done differently to avoid the early death of this young man.

During that summer, a letter arrived in the church mailbox from the resident chaplain at the London Psychiatric Hospital, inviting city pastors to join a half-day conversation group to focus on the mental-health issues that pastors face in their congregations. This conversation with seven others from mainline churches proved to be a healing experience for me. It also became a time when I explored the possibility of further education.

I found a one-year clinical pastoral education program at Crozer Theological Seminary, Upland, Pa., leading to a master of theology degree. The program included two academic courses per term and half-time work as a hospital chaplain.

With the Valleyview congregation granting my request for a one-year leave-of-absence, this became a pivotal year for me, as it opened for the first time the need to also work from my right brain. It was necessary to face the “shadow side” of my person. My unresolved anxieties, fears and anger, among other emotions, needed to be faced directly.

During that time I became aware of a supervisor-in-training position, so I negotiated with the congregation for a second year off. In exchange, I agreed to fly home once a month to preach, do some pastoral care and administrative planning. I coordinated preaching and pastoral care ministries, which were carried out by members of the congregation. In the process of our discussions, an exciting new vision developed within me and the congregation for team ministry as a viable leadership model for Mennonite congregations.

Over the course of this second year I completed my research for my master’s thesis, as well as fulfilling the requirements for the supervisory training program all while flying to London 10 times that year. I started fleshing out a new vision for pastoral education as I prepared for certification as a chaplain supervisor. Rather than using a hospital or seminary classroom, a congregation would be the primary base for one half of a student’s ministry training, with the other half spent in a mental hospital context or a social ministries setting. As well, students would take one class in a seminary of another denomination.

With this vision I approached the AMBS dean, Ross Bender, in the fall of 1968 about the possibility of following through on this vision. This alternate model for equipping pastors was implemented a year later and continued for the next 10 years.

Congregational faith formation

The Mennonite church has stated that the congregation is the central reality for gathered Christians. It is in this context that worship, education and fellowship occur. In this setting members also care for one another. Ideally, the congregation is a welcoming place for those searching for a meaningful focus. In fact, the current buzzword is that we should be a “missional” congregation.

To move in this direction means that our congregations must be much more intentional in their discernment and mutual accountability. The virus of individualism has seriously infected our congregations. It is, in fact, at the pandemic stage. Our congregations must become places where people engage meaningfully with each other. Too many of us still resist being open about questions of faith, the use of our financial resources, or even about our emotional and mental struggles.

It is this reality that Stuart Murray is addressing in his book The Naked Anabaptist, recapturing for us this dynamic for a revitalized community in the 21st century. Following his prescription will more readily make us a missional people. My hope is that congregations would find fresh ways to engage Scripture as a living, relevant resource for living as a countercultural people in their communities.

We are being bombarded daily with messages that run counter to what we believe. When we engage one another in Scripture-seeking to live faithfully, there is the potential for being a vibrant, welcoming people of God, attractive to those searching for more meaning and purpose in their lives.

Church pastoral teams need to access Bible study aids that provide background information as well as possible interpretation of the text. For me, it was helpful to explore how the Bible came together in its present form. In 2004, I revisited this subject when John Miller, a professor at Conrad Grebel University College, Waterloo, Ont., published his book How the Bible Came to Be. This served as a refresher to what I had known, but it also brought into focus some of the more recent findings, such as the beginnings of the canon, expanding my understanding of the sacred text and giving me a greater appreciation for the biblical story.

There are many commentaries and Bible study helps available to us. The Believers Church Bible Commentary Series covers many of the books of the Bible. This material is quite accessible to serious students as a reliable source of information.

When our congregants diligently search Scripture, it may help us avoid rehashing our former interpretations and patterns of behaviour. It will hopefully create renewal and a revitalized congregation. This also means that congregations may need to work at creative ways of keeping their church programs relevant, or delete them, in order to provide the time to carry out the vision.

Practising biblical stewardship

Congregations must encourage the practice of “first fruits” giving. A discipline to set aside a portion of one’s income at the front end should help us set a goal of giving 10 percent to God’s work in the world, the primary recipient being our congregation, then other charities.

If one has limited resources, it will be necessary to begin with a smaller percentage. Jesus noted that two small coins that were given by the widow were significant: “Truly I tell you, this poor widow has put in more than all those who are contributing to the treasury” (Mark 12:43). We are called to be responsible for the resources we have, whether they are limited or abundant.

Making first fruits giving a regular practice also helps our overall stewardship by providing a way of sorting out our basic needs over what may be less necessary. Our society puts a lot of pressure on us to buy more, which only feeds into our selfish nature. It is in this area that the congregation can help us to be more countercultural. We should not worship the god of consumerism or the lottery god in an effort to hopefully win easy money.

The offering is a meaningful act of worship, ranking alongside the singing of hymns, praying, Scripture reading and preaching. In his book A Christian View of Money, Mark Vincent sees the offering as a sacramental act. He encourages congregations to experiment with a variety of approaches in receiving the offering. On occasion, congregants could be invited to bring their offering to the front of the sanctuary, an act that can be a powerful symbol of commitment.

In 1994, the Mennonite Foundation of Canada published a helpful booklet, Money Management and Financial Planning, one of a variety of resources available to congregations.

Environmental stewardship is a front-burner issue for the church, which is concerned with how much we travel and our use of non-renewable resources. It is encouraging to see more “green” initiatives each year. The Greening of Sacred Spaces Project headed by Jane Snyder in Ontario’s Waterloo Region is another positive example of moving towards a more responsible pattern of living. The use of solar panels, water preservation initiatives and recycling are but a few of the ways we can be better caretakers of God’s world.

It is encouraging to read that young people are taking leadership in environmental stewardship. Rockway Mennonite Collegiate, Kitchener, Ont., and Conrad Grebel have taken the initiative to have solar panels placed on the roofs of their respective institutions.

A year ago, Grebel also became the first residential institution to join the Green Bin Organic Waste pilot project operated by the Region of Waterloo. In eight months, almost 10 tonnes of waste was diverted from the local landfill. Students also used a variety of methods to challenge each other to conserve energy and water. The university college has also become a member of the local Car Share program.

Words for new pastors

- Find your spiritual centre. How do you encounter the divine in your experience? Does God come to you through silent reflection and meditation on the written Word of God? Perhaps the Spirit speaks in the midst of dialogue with other people? At times I also encounter God in the midst of activity, particularly when sitting back to reflect on the question: Where has God been at work in this experience? At times these observations become clearer in dialogue with others.

- Maintain a balance. You have only so much time and energy. Prioritize your duties. Budget your time for sermon preparation, visitation and other pastoral duties. There will be some tasks that can be carried out by your congregants, such as visiting new mothers at the hospital.

- Allow time for prayer and reflection to be alone with God. Nurture your own soul on a regular basis; otherwise, you will be ministering on an “empty gas tank.” Pace yourself so you can give time for your family and other social relationships. Receive adequate rest as well as regular exercise.

- Find a trusted, experienced pastor to walk with you. This is especially important in the first five years of ministry. Covenant to share openly with this person, giving you a sounding board for issues you will face in your ministry. Pray together. You should have a good support system both within the congregation as well as in your area church. These early years are significant in assuring that you will have a productive and enjoyable ministry experience.

Observations and growing edges

There is a growing appreciation for “mystery” in my Christian walk. Mennonites have tended to be so literalistic in their interpretations, whether of Scripture or of their statements of faith. When participating in communion or a baptism, one can be fixated on the physical elements of bread and juice, but miss the power and beauty of the powerful symbolism of these experiences. Given the limitations of my religious history, I have gradually gained an appreciation for the numinous in my life, namely, having a sense of the presence of the holy.

The concepts of grace, repentance and perfection have increasing relevance for me. We do not always act in graceful ways, nor do we appropriate the concept in relation to our emphasis on discipleship. I echo Philip Yancey’s question in his book What’s So Amazing About Grace? When we emphasize service and right behaviour, the tendency is to become rigid as we identify ways in which to live faithfully. We often lose the expression of grace as we seem to forget that we, too, are redeemed sinners. It is in these times that perfectionism manifests itself.

Will Braun discussed our motivations when we serve others in the July 11 issue of Canadian Mennonite. While our motives are never totally pure, we continue to serve. Yes, we must continue to examine our motives and be open to repent of our sinful motivations. Grace and forgiveness come to us as we repent and continue to minister in the name of Jesus.

Perhaps Jesus’ parable of the weeds and the wheat gives us a possible clue as we deal with this issue. This story is part of a series of parables in which Jesus compares the kingdom of heaven to a variety of everyday activities with which his hearers would have been familiar. In this one he compares the kingdom to good seed. At night, the enemy plants weeds among the wheat seeds. The slaves discover the weeds when the plants begin to grow. They ask whether they should pull the weeds. The master says no, because, if they pull the weeds, they will also pull out the wheat. The text says, “Let them grow together until the harvest.” At that time the reapers will separate the weeds form the wheat.

However questionable it is to formulate church practice out of a parable, this does point to a truth: When dealing with motivational and behavioural issues, we should not be too quick to judge by pulling “out the weeds,” thus possibly destroying the individual in the process. As Yancey says, “Grace comes free of charge to people who do not deserve it.”.

Ralph Lebold’s autobiography, Strange and Wonderful Paths: Memoirs Of Ralph Lebold, was published by Pandora Press in 2006. To order a copy, e-mail info@pandorapress.com. The author is pictured at a book signing at Conrad Grebel University College in the summer of 2006.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.