Participants at the International Ecumenical Peace Convocation (IEPC)—held in Jamaica last month to celebrate the end of the Decade to Overcome Violence—released a message expressing their unified experience of a week-long exploration of a just peace and ways to navigate a path forward as they return to their homes and churches around the world.

Attempting to take into account each other’s varied contexts and histories, participants were unified in their aspiration that war should become illegal and that peace is central in all religious traditions.

The message states: “With partners of other faiths, we have recognized that peace is a core value in all religions, and the promise of peace extends to all people regardless of their traditions and commitments. Through intensified inter-religious dialogue we seek common ground with all world religions.”

The participants acknowledged that each church and each religion brings with it a different standpoint from which to begin walking towards a just peace. Some begin from a standpoint of personal conversion and morality. Others stress the need to focus on mutual support and correction within the body of Christ, while still others encourage churches to commit to broad social movements and the public witness of the church.

“Each approach has merit,” stated the message, which was crafted by a seven-member committee chaired by Bishop Ivan Abrahams of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa. “They are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they belong inseparably together. Even in our diversity we can speak with one voice.”

Abrahams hopes that convocation participants will find their voices in the message. “In many ways, this convocation is a milestone in the march toward just peace,” he said. “The words ‘reaping’ and ‘harvesting’ have been intrinsic to the life of this convocation. This message is to ourselves, to our churches and related organizations, and to the world that is bruised and broken, and that God so loves.”

The message also acknowledges that the church has often obstructed the path towards a just peace: “We realize that Christians have often been complicit in systems of violence, injustice, militarism, racism, caste-ism, intolerance and discrimination. We ask God to forgive our sins, and to transform us as agents of righteousness and advocates of just peace.”

The IEPC message captures only part of a truly historic event, said the Rev. Dr. Walter Altmann, moderator of the World Council of Churches (WCC) Central Committee, as he received the IEPC message on behalf of the WCC. “You take with you much more than a text; you take with you a profound ecumenical experience,” he said.

The ending of WCC’s Decade to Overcome Violence is also a new beginning, Altmann added. “As we return, each of us becomes a living message for the IECP,” he said.

The IEPC participants responded to a reading of their final message with a standing ovation.

The general secretary of the WCC, Rev. Dr. Olav Fykse Tveit, expressed his pride to the IEPC participants who challenged themselves and each other to reach new levels of understanding and determination. “We are called to be one in our witness,” he said. “We also see that the way to just peace has united us. This is a gift for all of us and we shall use it well.”

The final message may be complete, but the work of the IEPC is only beginning, said Fernando Enns, a German Mennonite theologian who proposed the Decade to Overcome Violence and was moderator of the preparatory committee for the IEPC. “We are only beginning to grasp the possibilities we have when we really respect one another,” said Enns, who now teaches Mennonite peace theology and ethics at the Free University of Amsterdam, Holland. “The church shall not speak to the marginalized; the church is where the marginalized are.”

Convocation participants should celebrate their experience, but Enns believes they should not rest satisfied. “Our journey must continue,” he said. “You and I, we shall hold each other accountable. The church is either accepting the call to just peace or it is not the church at all.”

Peacemaking can be rooted in theology and mission

Making peace an integral part of the life of church mission and witness has not been as common as some might think. Rather, the opposite seems to be true, as the church throughout history has found itself pointing the sharper—rather than the blunt—edge of the sword, many times using violence in the name of God. Following closely behind has been mission and theology, either justifying it or keeping silent.

Is it possible there is a non-coercive expression of mission and theology that can move the church toward being a peacemaker?

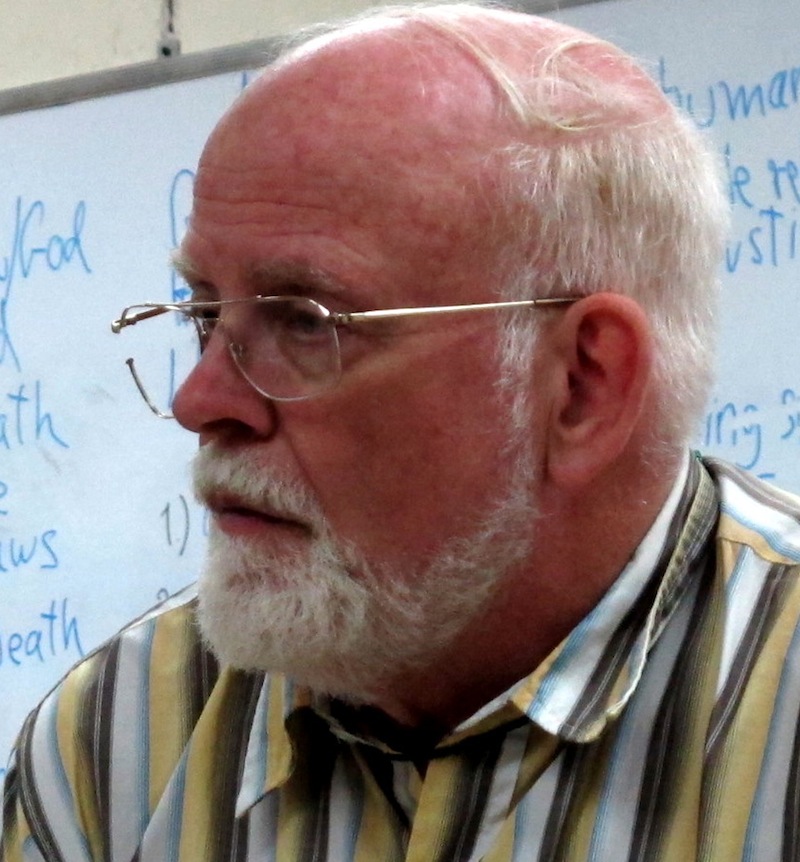

For Thomas Finger, a former professor of systematic and spiritual theology at Eastern Mennonite Seminary, Harrisonburg, Va., this was the point of discussion during a convocation workshop he led. Entitled “Peace: The lens for re-visioning Christian theology and mission,” participants explored Finger’s views about peace, justice, salvation, sin and Jesus’ mission.

He explored classic theological assumptions, one of the strongest being that violence is central to the theological concept of sin. “If the way that led to death is violent, the way that leads to life cannot be violent,” Finger suggested, adding, “Sin is not only the personal breaking of divine laws, but also the corporate turning away from and losing sight of God, peace and justice.”

By proposing complementary approaches to Christian theology, Finger said this would help churches and individuals focus the experience of their faith on the core of Jesus’ message, which is peace. Finger, who joined a Mennonite Church U.S.A. congregation at the age of 38,

helped workshop participants reach the consensus that, through the lens of peace, theology could be more than “the clarification of the articulation and the testing of our basic conditions.”

One of these basic conditions is that people think life is a struggle. But life can be something different, he said, citing the possibilities of relationships and peace. People can also reverse the current “logic” of violence through the strength of their faith and commitment. “The resurrection itself reversed the logic of violence and condemns those who killed Jesus,” he concluded.

Finger, who maintains a dialogue with elements of both Orthodox Christian theology and liberation theologies, said the Holy Trinity is essential for any theological reflection and a perfect model of peace, inviting human beings to live in communion through the event of the resurrection.

Finger also echoed some elements of liberation and contextual theologies, especially when analyzing structural sins and defending liberation for renewal and the establishment of peace and justice.

–May 26, 2011

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.