As prayers began, a hush fell over the crowd and numerous people pointed to the sky. The great spirit, the eagle, hovered overhead. Surely it was a clear sign of God’s presence and blessing as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) launch in Winnipeg, Man., drew to a close on June 19.

The stories I heard were many: a mix of pain and hope, of betrayal and determination, and, very often, a testimony to the strength of Canada’s aboriginals.

“I am a survivor of a survivor,” said one young man.

A survivor of a survivor. That hit me like a rock. A man of few words, he concealed the truth of his troubled life beneath baggy clothes and a slouch. He was one of several who had walked 1,400 kilometres from Ontario to participate in the Youth Sharing Circle, and although he had clearly lived a tough life he was on a journey of self-discovery about residential schools, and thus about himself.

Another young man had been taken away from his mother when he was eight days old. Child and Family Services (CFS) raised him, bouncing him from home to home. He never bonded with anyone, never knew love. “They say that IRS (Indian Residential Schools) ended back in the 1980s, but they didn’t because CFS is part of the same system,” he said. “This is now seven generations, and these seven generations are sitting around this circle today, and the prophecies say that the seven generations will change the world, and that’s us,” he said, speaking proudly of the strength of his people.

A white high school history teacher spent five days at the sacred gathering listening to stories of pain and abuse. “I learned more about Canada in the past five days than I did in my three-year history degree,” she said. “We have to begin teaching our children about all of our history. The residential school situation has maybe been a single page in a textbook, and not even always.” She spoke about the strength of survivors, and how honoured she felt to be a listener.

Mennonites were not excluded from these stories. After a man shared his story of abuse in residential schools, of moving on, of how important family is, and that he loved his wife of 43 years, he said that she went to a Mennonite-run school. It was just as bad as all the others. How come, he asked, aren’t the Mennonites here?

I approached him immediately following the session to tell him that we are here, and that we care.

Another survivor described a vivid and horrible incident of being beaten under the careful supervision of the principal and four staff members at a Mennonite-run school. He wanted to record his story to let people know that abuse happened beyond the schools addressed in the Indian Residential School Settlement—and he wanted Prime Minister Stephen Harper to hear his story: “Two years ago the Prime Minister apologized. Two years ago was a sad day. My son committed suicide on the day of the apology. It was too late for him.”

An impish, tiny girl with little-kid overalls and long flaming red hair reminded me of Pippie Longstocking, but she was 18 years old and about to graduate from high school. How does she fit here? I wondered.

Her explanation resonated deeply. “What one part of my heritage—my mother’s white side—has done to the other part of my heritage is tearing me apart,” she said. “And I won’t feel together until the world is made right. I feel shame and anger for what we did. It is wrong. It is inexcusable.” Métis and full of fire, she was appalled that she had never learned about this aspect of Canadian history in school.

She could well be speaking for all of us. It is much easier to say “it wasn’t us.” But it was us. Christians professing Jesus and dedicating their lives to service, somehow—for reasons we will never understand—were given complicit approval to look upon First Nation, Métis and Inuit children as less than people created in the image of God. Blind eyes were turned. Indifference ignored suffering. Sanctioned and even supervised beatings were carried out. Church people took vulnerable boys and girls into their rooms late at night to fondle and sexually abuse. Repeatedly. Persistently. Consistently. And successor staff did likewise.

As these stories connected with other stories from faraway countries, indignation flared, forcing tears to my eyes. I was angry. I am angry. How could people, good people, people like me, do this?

Embroidered black words emblazoned the centre of a quilt formed from Hudson Bay blankets: “Canada has no history of colonization. –Stephen Harper, PM Canada, September 2008.” Around it are words of disbelief, indignation and sarcasm: “Then we also have a long history of amnesia. . . . Is this blanket infested too?” and so on. It is a poignant reminder that even a short 15 months after Stephen Harper issued the well-cited formal apology, we still don’t understand.

Perhaps a sign of hope on that Saturday afternoon of images were the words of Chief Justice Murray Sinclair and Governor General Michaëlle Jean, both of whom attended the Youth Sharing Circle. Sinclair spoke in a gentle yet direct way to the youths who shared the pain.: “Your aunties are telling us that the impact of the residential schools must stop here.”

He spoke simply and profoundly on the question of identity. “To know who you are, you need to know where you come from, your clan, because your clan tells you your responsibility in the community. You need to know your spirit name. It is only when we know who we are that we have self-respect and mutual respect, both of which are essential in the process of reconciliation.” And then he said, “It was through the educational system that we got into this, and it is through education that we will get out of this.”

Jean took both hands of each participant in the circle and kissed each one on both cheeks. The boy who had been raised in CFS without bonding or knowing love, reached out to her. They wrapped their arms tightly around each other in a long embrace.

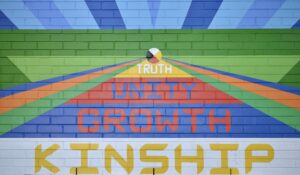

“We need to break the walls of indifference,” Jean said. “We are laying a new foundation for this country by confronting together our past.”

My emotions are still somewhat raw from that incredibly moving afternoon and the tears come easily. Lord have mercy. Lord, can you forgive us? Thank you for your forgiveness.

Janet Plenert is executive secretary of Mennonite Church Canada Christian Witness.

See other stories related to the 2010 Truth and Reconciliation Commission events:

“How complicit are Mennonites in Residential School Abuse?” Evelyn Rempel Petkau attended the first TRC hearings and spoke with Mennonites about whether the church might be complicit in the system.

“With God, all things are possible” A residential school survivor recalls childhood abuse and his quest to forgive his tormentors.

“MC Canada shares the pain of Indian Residential School legacy” A report on discussions at Mennonite Church Canada Assembly 2010

“Mennonite treaty rights” The implications of Treaty 1

“Forgiveness to what end?” An editorial on accepting and offering forgiveness

“For discussion: August 23, 2010 issue” Questions for reflecting and discussing

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.