"I don't want to remember it,” Hugo Unruh says of the grim spring day in 1972. He and his wife at the time, pulled into the 40-hectare complex an hour west of Winnipeg that then housed 1,000 people with intellectual disabilities with Nick, their 13-year-old son.

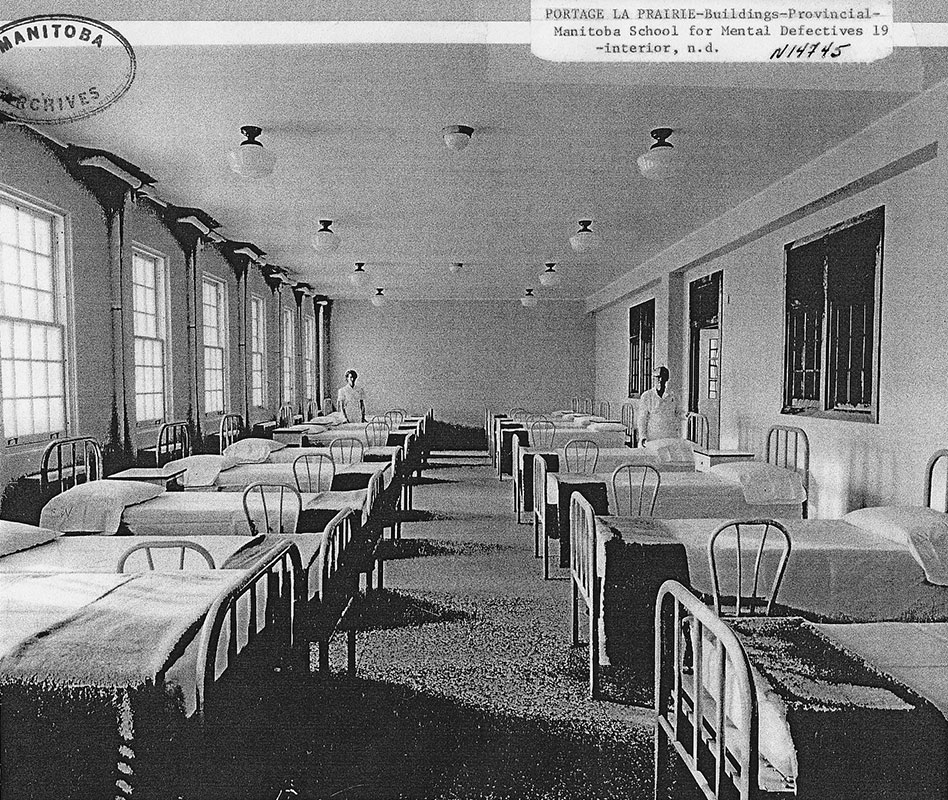

"I just about died when I saw it," he says of the stark 30-bed dorm room that would end up being his son's bedroom for the next 15 years at the Manitoba Developmental Centre (MDC). "My wife was in tears," says the retired United Church minister, explaining that they were simply not able to care for Nick at home, due to his cerebral palsy and complicated medical needs.

The feature article that surrounds this piece speaks movingly about the profound and historically overlooked gifts that people with intellectual disabilities can offer the church and world. Part of reconciling ourselves to these gifted people requires healing a lingering history of societal treatment that is anguished.

And awkward. Over its 124-year history, MDC has been called the “Home for Incurables,” “the Manitoba School for Mentally Defective Persons,” and the “Manitoba School for Retardates.”

Former residents speak of solitary confinement as a form of punishment, physical abuse, hunger, absence of privacy, lack of personal choice, and a climate of fear. David Weremy told me how he once informed his mother of abuses he’d witnessed at MDC. After his mother asked staff about it, Weremy was locked up in solitary before he ultimately ran away. The 2008 National Film Board-sponsored documentary, The Freedom Tour, recounts many similar stories.

An Ontario judge recently approved a $67-million payment to survivors of the province's last three MDC-like institutions, which closed in 2009. Premier Kathleen Wynne issued an apology to residents and families who, she said, were "deeply harmed and continue to bear the scars and the consequences" of the facilities. "Their humanity was undermined," she said.

As recently as 2006, about 3,800 people with intellectual disabilities lived in 31 large facilities across Canada. Today there are about 430 people, divided between MDC and the St. Amant Centre in Winnipeg. The Alberta government is in the process of closing its last large residential buildings at Michener Services in Red Deer, and Saskatchewan says it will close Valley View in Moose Jaw by 2016.

That leaves only Manitoba stranded on the wrong side of history. But it's complicated. Family members of residents at Michener are fighting hard to keep it open.

Unruh knows the complexity. As difficult as it was for his son to be at MDC, it was an improvement over Nick's previous placement. There, he said, Nick was “so medicated he couldn't hold up his head.” MDC staff reduced his meds and taught Nick to communicate using a system of symbols, something that transformed his life, and, ironically, allowed him to communicate his dislike for MDC.

Since 1987, Nick has lived at a group home in Winnipeg. Hugo and his wife Carol, whom he married in 1985, host Nick every weekend and are an intimate part of his life. Unruh says he sympathizes with people who have loved ones in MDC and choose to keep them there. He understands the emotional stakes.

Families whose loved ones have spent decades in these places presumably do not want to feel like they have done wrong by allowing this. Their concern must be applauded and given close attention.

But the stakes for people who suffered abuse in institutions are equally high. They deserve to see a clean break from that era. The knowledge that these institutions still exist consumes people like Weremy. Society owes these people a generous measure of healing.

And it owes an equally generous measure of grace to current residents and their families. Many families say the institutions should remain open because their loved ones have lived in the facilities for decades, so a move would be traumatic, and because medically fragile residents cannot be cared for elsewhere.

Advocates for closing the facilities point out that thousands of people have been successfully transitioned from large institutions to group homes or individualized settings. A Brock University study found that, following the last round of closures in Ontario, 93 percent of families "reported they were satisfied with the placement" of their loved ones.

Experience and studies also show that medically fragile people can be well cared for in community settings. The Brock researchers made recommendations that focus not on whether community living is preferable to institutional life—that is no longer a question in most of the country—but on how to maximize the chances of smooth, gentle transition. Careful, proactive and highly individualized planning are key recommendations.

Where does the church fit in? I have found no evidence of church groups speaking out on this topic, although various faith-based organizations provide services for people with intellectual disabilities. An important and difficult reconciliation is happening with respect to the societal place of people with intellectual disabilities. The church should be there—informed by the spiritual attentiveness portrayed in “Good work: Tales of disability, interruption and revolution” on page 4—to provide accompaniment, practical support, wisdom and perhaps conflict resolution services.

Renowned ethicist and author Margaret Somerville, whom I interviewed on the topic in 2010, says: "You test the ethical tone of a society by how it treats its weakest, most-in-need, most-vulnerable people." That is the opportunity before us.

This article is based on interviews and research done between 2010 and the present, parts of which have been published elsewhere.

–Posted August 28, 2014

In the web-exclusive piece, "More viewpoints: Differently gifted," Will Braun gives links to more background on this topic.

See also the Canadian Mennonite feature, "Good work" (Sept. 1, 2014 issue), which explores how the church relates to people with intellectual disabilities.

LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0geyBtYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAzMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbiB7IGJvdHRvbTogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcik7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDAgMCA1cHggMDsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IHVse2xpc3Qtc3R5bGU6bm9uZTttYXJnaW46MCAwIDEuNWVtIDA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse21hcmdpbjowICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3RvcDowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHtncmlkLXJvdy1lbmQ6dW5zZXQgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6OmJlZm9yZXtjb250ZW50OiIiO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3BhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxsOjptYXJrZXJ7Y29udGVudDoiIn0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgaW1ne2hlaWdodDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7d2lkdGg6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7YWxpZ24tc2VsZjplbmR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczpyZXBlYXQoMTIsIDFmcil9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1jb2xsYWdlIGltZ3toZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MDtncmlkLWF1dG8tcm93czoxcHg7b3BhY2l0eTowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgaW1nLC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpZnJhbWUsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHZpZGVvey1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt3aWR0aDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7ZGlzcGxheTpibG9ja30udGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbntwb3NpdGlvbjphYnNvbHV0ZTtib3R0b206MDt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjYpO3BhZGRpbmc6NXB4IDJweDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtjb2xvcjojMzMzfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uOmVtcHR5e2JhY2tncm91bmQ6dHJhbnNwYXJlbnQgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgZmlndXJle2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IGltZ3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDoxMDAlOy1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjpib3R0b219I2xlZnQtYXJlYSB1bC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5e2xpc3Qtc3R5bGUtdHlwZTpub25lO3BhZGRpbmc6MH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uIHsgYm90dG9tOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHsgcGFkZGluZzogMCAwIDVweCAwOyB9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb24geyBib3R0b206IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgeyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgeyBwYWRkaW5nOiAwIDAgNXB4IDA7IH0gIH0g

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.