Take almost 200 mostly Mennonite peacebuilders from around the world, bring them together for four days in June 2016, at Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo, liberally mix in keynote speakers, 30-plus workshops, warm sunshine, a concert and original play on conscientious objectors, and you have the making of a fabulous four days of building peace in the world—a world where there is none, or where it is in too-short supply, or where there is peace but it can be grown bigger—all nonviolently but passionately, and with painful honesty and humility.

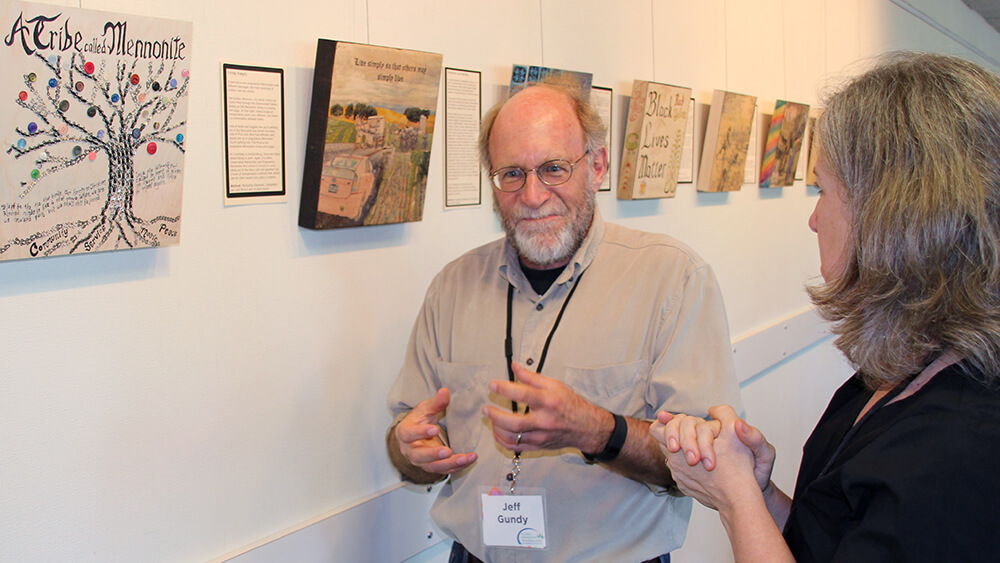

Originally conceived of a conference to coincide with the 2015 Mennonite World Conference assembly, the event became not just a conference—but a festival that approached peacebuilding from other angles, including music, storytelling, drama and art.

Theology, sociology and art were intermingled from the beginning. On June 10, Fernando Enns, director of the Institute of Peace Church Theology at the University of Hamburg, Germany, looked at how Mennonites have both influenced and been influenced by ecumenical engagement, especially through the World Council of Churches. He was followed by Paulus Widjaja, director of the Centre for the Study and Promotion of Peace at Duta Wacana Christian University in Jogjakarta, Indonesia, whose talk focussed on the social construction of violence and how to work at change depending on where a community finds itself in relation to other faiths. Then Lisa Schirch, a research professor at the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Va., described a series of eight paintings she created to promote peacebuilding in various situations, like the current discussion about inclusion of lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender/queer members in Mennonite Church U.S.A., under the title “Tongue screws on Pink Mennos.”

Other arts components included a concert featuring Gamelan, an Indonesian ensemble of percussive instruments directed by Masie Sum, an assistant professor of music at Grebel, which came together with the University of Waterloo Choir and the Factory Arts String Quartet to premiere “Earth Peace” by Carol Ann Weaver on June 9. Two nights later, Theatre of the Beat premiered its new play, Yellow Bellies, that explores the experiences of conscientious objectors in Canada during the Second World War through first-person narratives, letters and the media of the day. Live music was provided for the play by No Discernible Key, a local blues, folk and rock band.

June 10 and 11 began with “Stories for peace.” Dann Pantoja, a Mennonite Church Canada Witness worker in the Philippines, shared about bringing evangelical Christian leaders together with Muslim rebels for conversation and peacebuilding. With news of Canadians being killed by hostage-takers in the Philippines, Pantoja was asked about the danger in his work. “It’s just as dangerous,” he said, “as driving your car down the 401 [highway] to Toronto from Waterloo.”

Following the June 10 banquet, keynote speakers Steve Heinrichs, Mennonite Church Canada’s director of indigenous relations, and Leah Gazan, a member of Wood Mountain Lakota Nation, located in Treaty 4 Territory in Saskatchewan, spoke on “Giving up privilege, pursuing decolonization.” In order to make sense of this, the international visitors needed to be brought up to speed on Indian Residential Schools, the ’60s scoop and current conditions in first nation communities in Canada.

The workshops wrestled with questions like, “What for you defines Mennonite peacebuilding?” and, “Were the early Christians pacifist? Does it matter?”

Jennifer Otto, who co-leads an urban church plant in southern Germany in partnership with the Verband Deutscher and the Deutsches Mennonitisches Missionskomitee, answered the second question, saying they weren’t as pacifistic as some scholars have argued, and it doesn’t really matter as Anabaptists continue to apply the Bible today.

One workshop hit close to home with a study of the “Doctrine of discovery,” a belief that lands without Christian princes were empty and ripe for Christian conquering, while another looked at “white privilege” in Mennonite justice institutions like Mennonite Central Committee (MCC).

While one participant wondered about the low level of theological and biblical underpinnings for peace, others found the conference inspiring for the practical nature of many of the workshops in which the foundations of peacemaking were referenced.

Participants included a Kurdish man married to a Dutch pastor, and a Muslim peacemaker from Asia who declined to be identified. MCC worked at bringing many peacebuilders from around the world to the conference, but even it could not overcome the denial of visas to 10, mostly African, peacebuilders.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.