While some creative arts like prose and hymnody have been accepted as natural forms of expression and worship in Mennonite churches, visual arts are often viewed with less certainty. For painters, sculptors and other artists who craft for the eye, this can be disheartening.

Sashira Gafic, artist, teacher and a member of First Mennonite Church of Winnipeg points out that we are made in the image of God our Creator, and as such God intends us to be creative in a variety of ways. She expresses concern that some people consider visual art a novelty rather than a tool for faith expression.

“We’re missing a whole other way of thinking about God and using the gifts that God has given us to praise him,” she notes. “We are created in God’s image and given this ability to create and we don’t use that gift visually, sculpturally, in media.”

Bev Patkau agrees. The quilt artist from Foothills Mennonite Church in Calgary designs seasonal displays for her congregation and helped organize an art exhibit for Mennonite Church Canada’s Assembly in Calgary 2010, contributing some of her own creations. In an interview at the exhibit, she said that visual art offers another venue to draw worshippers into a deeper, more prayerful connection with God.

“I think it nourishes the soul. I see it the same as walking through beautiful scenery outdoors and when we go inside, why do we have to stop seeing beauty?”

In the preface to her book The Substance of Things Seen Robin M. Jensen refers to the importance art and the Christian community hold for each other. Jensen, a Professor of History of Christian Art and Worship at Vanderbilt Divinity School in Nashville writes; “But even though the Christian community needs artists, the two worlds of church and art find themselves mutually wary, sometimes even hostile, often with little understanding or appreciation of one another. The church worries that art will go ‘too far’ and draw attention to itself rather than lead the faithful to God. The artists fear that the church will direct or limit their imagination and judge, censor or abuse their creativity.” (Eerdmans Publishing, p ix)

Despite this tenuous relationship, some artists have found creative ways to express missional faith through their craft. Ray Dirks, curator of Mennonite Church Canada’s Mennonite Heritage Centre Gallery (MHC Gallery), is a gifted artist who leads workshops with artists of other cultures and faiths to promote acceptance through a common desire for human dignity. His work builds connections between individuals and enhances relationships with other faith groups.

In the Spirit of Humanity

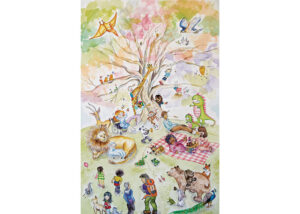

Sometimes the art is accomplished but more often than not it appears child-like and innocent, at least at first glance. Simple brush strokes and bold primary colours flow across canvas or paper to create familiar subjects. Flowers. World flags. Kites. People. Yards and houses. The earth, from an outer-space perspective.

But in some paintings a closer inspection reveals more: a pretty house and yard are blotted with spots of red; a car driving along the road is actually a military vehicle with prisoners inside; the prisoners are ordinary people. A seemingly innocuous row of city buildings towers over a machine-gun spraying bullets.

Not all of the images are despairing. In one depiction of earth-from-space, a black hand and a white hand reach across the foreground to clasp each other tightly in a clear display of unity. In another painting, red flowers bloom across a green meadow and entwine a tree trunk. The artist of that piece describes it as a metaphor for life and the way we must all grow together.

Each of these works were inspired by In the Spirit of Humanity, a MHC Gallery project supported by the Winnipeg Foundation, Welcoming Communities Manitoba and Manitoba Education. The project was designed to encourage sharing, respect and acceptance of one another across cultural and faith differences.

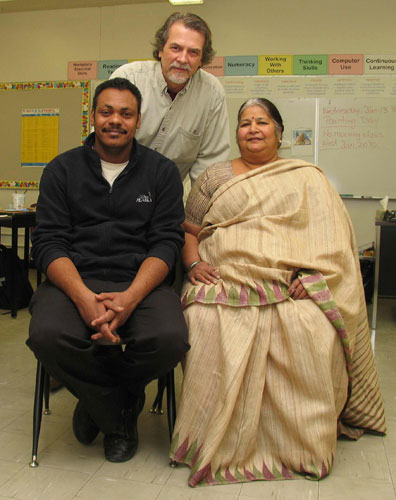

In the Spirit of Humanity brings Dirks with his friends, Hindu artist Manju Lodha and Muslim artist Isam Aboud, into school classrooms and English-as-an-Additional-Language (EAL) settings across Manitoba. The artists share stories about their relationship, their individual life experiences and their art. These visibly distinct people with vastly different roots use heartfelt words, music and a PowerPoint presentation to open up about themselves in a deeply personal way and then encourage students to reciprocate on canvas or paper.

“The three of us come from three different places but we all want peace and to work together,” says Lodha to a class of Grade 8 students at H.C. Avery Middle School in Winnipeg. “Together we are so much more than we are apart.”

Roots

Lodha was born and raised in Jaipur, India but has lived in Canada with her husband for 38 years, longer than she was in India. While she is proud to be Canadian, she still connects strongly with her roots. The unique mix of experiences that shaped her find their way into her paintings and poetry. An exhibit of her works at the MHC Gallery in 2007 helped her find a way to connect with the world through art.

Aboud met Dirks in 1998 as a refugee from Sudan living in Nairobi when he participated in a Mennonite Central Committee-sponsored Sudanese Muslim art exhibit Dirks organized. When Aboud immigrated to Canada in 2004 with his wife, he landed in Winnipeg and reconnected with Dirks over the telephone.

For anyone who may feel slightly cocky about not being different, Dirks levels the playing field. “If you are not First Nations, your roots are somewhere else.” Although Ray is a second-generation Canadian, he traces his own roots back from Russia to Holland. “I always compare my family story with Isam’s and say that, in many ways, they are the same—both stories of refugees coming to Canada. They just happened at different times.”

After their presentation, Lodha and Aboud start new paintings and invite students to come and watch. They take time, as does Dirks, to mingle with the students who are pouring reflections of their own onto canvas.

Some paintings make obvious inferences, like Philippine flags of which there are several, or an eagle, an important symbol in Aboriginal communities. Some are more ambiguous, depicting music notes, or a sunset, or an open door glowing yellow on a background of grey. A few of the young artists are happy to share the stories behind their paintings while others are more reserved. But even for those who aren’t ready to discuss their work, the physical act of painting gives them an opportunity to consider the importance of their experiences and individuality.

For the betterment of all

“The world used to be out there, but the world is now our neighbour,” Dirks says later during an interview at the gallery. He sits behind a desk piled high with art magazines and books. His desk is nestled behind a large number of crates; an art exhibit packed and ready to travel.

“As Christians we should know our neighbours and celebrate them…stereotypes are wrong or misplaced.” He explains that for acceptance to occur, people must be proud of who they are and where they come from.

“In schools, it’s amazing the effect it has on kids. Others shouldn’t be allowed to mock you or bully you. It is for the betterment of us all if we get to know and accept each other.”

Across from Dirks, Lodha warms up a variety of East Indian dishes for a lunch she intends to share with us, filling the air with scintillating aromas.

“Be proud of who you are and of your heritage,” she says. A country that accepts people for who they are will find strong supporters in those people. She summarizes the philosophy of In the Spirit of Humanity; “We can all teach, we can all learn. If we take that attitude we can’t help but be a better country.”

Lodha admits that it was difficult finding her place in Canada on her own. “But like a rope, with the others there is more opportunity, more strength because we are intertwined.” The pair have numerous stories to share from workshops, including one about a young boy who chatted enthusiastically with Dirks for some time after the session was over. The boy’s teacher approached Dirks later, marvelling at the child’s sudden outspokenness. She pointed out that the boy who never talked was now laughing and playing with other children in the classroom.

Lodha shares a reaction to a photo of dried eels and caterpillars, considered food in some communities. Students were asked if anyone had eaten these foods before. A Congolese girl enthusiastically responded, “Yes, I eat caterpillars. And they’re good.” In the Spirit of Humanity stresses the idea that customs like these are not right or wrong; they are simply different.

In one EAL class, an older Somali woman sang as she took brush to canvas for the first time in her life. Others joined in. As painful experiences from the past emerged around the room, the voices singing together began weeping together. The older woman painted memories of the day her husband was killed in front of her, while another Somali woman created images in memory of her husband and children who had died before she came to Canada as a refugee.

“The teacher later said she’d never seen this kind of reaction before,” Dirks recalls. “She said, ‘We spent so much time trying to help them blend in without saying we want to get to know you.’”

Dirks was so moved by the singing that he invited the women to sing at the opening of an exhibit of student art for In the Spirit of Humanity at the MHC Gallery—and they agreed. In yet another EAL class a woman from Bosnia painted the murder of her husband. When the trio of artists returned the next day to work with another group, the woman also returned. Why did she come back?

“I like very much,” she told Dirks. That day she painted flowers. It didn’t mean that everything was suddenly resolved, Dirks admits, but it demonstrated the power art can have as therapy and the impact the trio of visibly different artists could have by celebrating the intrinsic value of others.

“The instant we walk into a school, the fact that we treat each other with respect serves as an example. It’s great that we’ve come together.” By coming together, Dirks, Lodha and Aboud are finding ways to use the visceral, universal language of art to convey a strong, clear message about unity in diversity. They are using art in a way that defies traditional perspectives by engaging in a timeless mission.

Images of art used by permission of the artist and/or the MHC Gallery.

See more art in the gallery

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.