Last September, at the school where I teach, the director noted the many restraints and restrictions staff and students were experiencing because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It seemed that everywhere we turned, we were told we couldn’t do something. Many excellent teaching practices were out of reach because we needed to maintain social distancing.

I started to reflect on what restraint and restriction meant in my own life and faith. What relevance do these limitations have to the way I relate to those around me and to God? I miss singing in a choir! We miss getting together with our families and friends. We need to wear masks everywhere, and so much communication is hidden behind the mask. In many places, there are restrictions, and this is difficult even though we know that these restrictions are for our good and for those we love.

Are there biblical examples we can look at? In Philippians 1:12-14, the imprisoned Apostle Paul writes: “Now I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that what has happened to me has actually served to advance the gospel. As a result, it has become clear throughout the whole palace guard and to everyone else that I am in chains for Christ. And because of my chains, most of the brothers and sisters have become confident in the Lord and dare all the more to proclaim the gospel without fear.”

Paul’s imprisonment, far from ending his missionary activities, actually expanded them for himself and others; it broke bonds and barriers. Because he wrote these letters to the Philippians and other groups, we too can read them. We literally wouldn’t have the New Testament as we know it if he had not been restrained and had to write instead of visiting those churches.

The most obvious example was Jesus himself. Paul goes on in his letter to write: “Have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: who being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness.” It is difficult to contemplate what it means that Jesus took on the limitations of being a human being.

Visions of God

Julian of Norwich, a woman who lived in the 14th century, can also provide insight into our current situation. She wrote one of the earliest books in the English language.

As a young woman in Norwich, England, she likely was from a fairly wealthy middle-class family, married with several children. Then the Black Death struck. Her area was one of the worst hit by the plague, and estimates are that about 7,000 of the 12,000 people in Norwich died. Twelve years later, a second wave hit the town, and 23 percent of the population died, this time in a wave particularly hitting children. Some historians think that in one of these waves Julian’s entire family died.

At some point, Julian herself was on the verge of death and received last rites. But she survived and later wrote that, while the priest held a crucifix in front of her face, she received 16 visions from God. The first draft of her book was entitled Revelations of Divine Love.

Later, she decided to become an anchoress. This was a form of withdrawal from the world and was meant to allow the person to spend her life in meditation and prayer. Anchoresses (or male anchorites) would be shut for life into a small room attached to a church, with three windows: one for servants to bring food and carry away waste; one window facing into the church, so the person could listen to religious services; and one facing the street, so the person inside could provide counsel to those in need. This was very serious decision, one taken for life. When persons were ready to move into seclusion, a requiem mass was performed and they were literally shut in for lifelong self-isolation.

Julian spent the next 30 or so years contemplating her visions and the`ir meaning. It was then that she wrote the long version of her book. The combination of her life experiences, visions, self-isolation and meditation led Julian to some remarkable, even revolutionary conclusions. Literature and art of the period often focused on death and hell, penance and vengeance, as did much of the church instruction she would have heard. But Julian reached different conclusions as to what all that meant, as expressed in the title of her book. She concluded that the central message of God is love.

For Julian, love emanates from God. To her, God is not on high, for humans to look up at. God is all around, in everything. She wrote, “There is a spreading outwards of length, and breadth, and of height and of depth without end, and all is one love.” She wrote that God has always been present in everything, giving unconditional love. Human blindness makes this difficult to see.

The more she contemplated, the more this became clear. “And 15 years and more later, I was answered in my spiritual understanding, and it was said: ‘Do you wish to know your Lord’s meaning in this? Be well aware: love was his meaning. Who showed you this? Love. What did he show you? Love. Why did he show it? For love.’ ”

Julian was not naive; she had experienced suffering, pain, loss and fear. Yet she emphasized that God wants us to know we are strong enough to survive these things, because of God’s unconditional love. She wrote, “He did not say, ‘You shall not be perturbed, you shall not be troubled, you shall not be distressed,’ but he said, ‘You shall not be overcome.’ ” She comes to her most famous and optimistic conclusion that, because of the nature of the love of God, “All will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.”

Life lessons

What does all this mean for us today? During the restrictions of the pandemic, we have had plenty of time to think, to contemplate and—while we are not locked for life in a cell—we are experiencing a form of isolation.

First, there is clarity, and we see what is most important, sometimes in seemingly small things. With the warnings of a second wave of COVID-19, I was not sure that I would be able to hold my granddaughter when she was born. I thought and worried about this for months. Now, I realize, in a way I never thought about before, what a gift physical presence is.

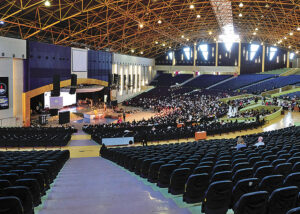

I no longer take gathering as a church family for granted. Many times in the past, I have gone to church, listened and contributed with perhaps a sense of duty. But losing the ability to gather with my church makes it clear how vital that gathering is for my faith journey.

Second, with slowing down and increased clarity, I have found a greater ability to listen to God. I notice things that I never have before. While I gardened last summer, I had time to observe each stage of growth in plants, to revel in the abundance of flowers and produce and beauty there. It was such a feeling of accomplishment to eat a tomato sandwich with homemade sourdough bread and garden-ripened tomatoes.

In my daily walks and runs outside, I started paying attention to the beauty in the sunrise and in the night sky. I noticed the changes in the moon, where the stars and planets are. This gives me a sense daily that “all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.” The inevitable passage of seasons is reassuring when I slow down enough to notice.

Since I could speak, I learned to give thanks for my food and for those who made it. These words of thanksgiving have become much more real to me. People, often those paid poorly and disregarded in society, put themselves in danger, and many got sick, to make sure food was in grocery stores and on tables. I never truly thought about what this meant, or really listened to the words of the table grace, “God is great and God is good.” What a message to remember when I stop and listen.

Finally, I have worked on my ability to trust in a new and real way. We have heard stories about our ancestors’ suffering, and we have all experienced sickness and death in our families, but now we have had to think about this as a group, as a community. Before, there were always food, jobs, doctors, and the idea that we trust in God for all these things didn’t seem, in a way, to be necessary. Now, we do things to protect our loved ones and ourselves, and we trust that “All will be well, all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.” Do we believe that God is great, God is good, and all things will be well? This requires learning to trust.

For me, and maybe for others, the limits in this time has brought many gifts. The chance to slow down, to see what is truly important in life. The time and inclination to see, to listen, to notice. The challenge to cultivate trust in an uncertain time. May these life lessons not be lost after the pandemic is over.

Brenda Epp attends Rosthern (Sask.) Mennonite Church and serves on the church’s worship committee. This is adapted from a sermon she preached there in November 2020.

For discussion

1. How has your life been changed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the need for separation from other people? In the past year of greater isolation, have you taken more time to reflect? Has it changed your sense of what is most important in life? Has your attitude toward suffering been impacted?

2. Brenda Epp writes that, after 30 years of self-isolation and meditation, Julian of Norwich concluded that “the central message of God is love.” Why is this surprising, given what is known about the life of Julian of Norwich? Do you think Christians of the 21st century accept this central message as true?

3. Julian of Norwich’s most famous conclusion is, “All will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of things will be well.” What do you understand this statement to mean? Why does this conclusion, from so many centuries ago, bring us comfort? Or does it?

4. What has your congregation learned about the importance of meeting together during the past months of pandemic restrictions? How might your congregation do things differently when the pandemic is over? What have we learned about being the church? Can you identify any gifts or life lessons that have resulted from the pandemic?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.