Over a period of seven years, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) heard more than 6,000 survivors of residential schools tell their painful stories of injustice and abuse. With the TRC’s work in hand, Christian churches can help write a better next chapter.

A group of us from across southern Ontario started this new chapter at a retreat held from Nov. 12 to14, 2015, at Six Nations of the Grand River, near Brantford. Indigenous and non-indigenous participants gathered for the weekend to talk, eat, dance and work towards reconciliation.

The retreat grew out of a conversation circle based in Kitchener-Waterloo, consisting of representatives from Mennonite and Lutheran churches, Six Nations Anglican and United churches, and people from traditional indigenous backgrounds. The weekend was sponsored by an ecumenical group that includes Mennonite Church Canada, MC Eastern Canada and Mennonite Central Committee Ontario.

Our speakers, Rick Hill and Adrian Jacobs, both from Six Nations, started the retreat by situating the relationship of settler and indigenous peoples in the context of colonial discourse and cultural genocide, making many of us realize the gaps in our understanding of settlement and treaty history.

On Nov. 13, we participated in a ceremonial Mohawk welcome that gave us deerskin to wipe away our tears, an eagle feather to unstop our ears and water to clear our throats. We were then asked to reciprocate the welcome.

“Watching the settler group struggle with knowing how to welcome the indigenous group was the beginning of my emotional journey during the retreat,” said Mim Harder of Rouge Valley Mennonite Church, Stouffville. “It was hard not to step in and help them. They truly struggled to be culturally sensitive, and to make the welcome meaningful. It brought tears to my eyes when the welcome was finally brought to us because it was brought from the heart.”

People and places speak louder than reports and figures, so visiting the former Mohawk Institute Residential School and the Mohawk Chapel, where the children attended Sunday services, were crucial experiences in learning to honestly face the past.

“It is hard enough to hear the stories of residential schools, but to be in one, listening to the survivors’ stories and feeling the spirits that linger there, is heart-wrenching,” Harder said.

Later, we turned our focus to the future by discussing the 94 calls to action outlined in the TRC report, a document that calls on all of Canadian society, including churches, to achieve concrete and timely goals.

We focussed on three calls to action—Nos. 48, 59 and 60—that deal with education within congregations, curriculum within religious educational institutions and the commitment of faith groups to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

What does it mean to “respect indigenous spirituality in its own right?” What does it mean that our churches sit on treaty land?

We worked through these calls in lament, frustration, clarity and hope. No one ever promised that reconciliation would be easy, but we found that stories can provide great wisdom for the road.

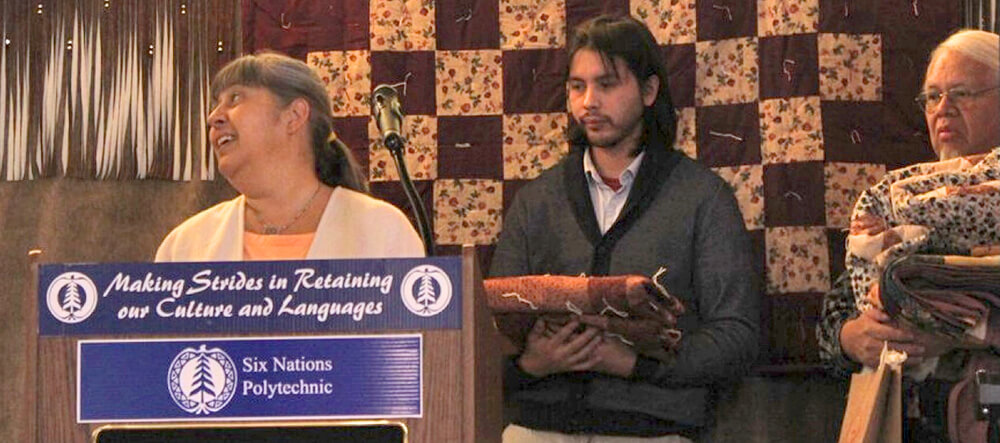

Taylor Gibson, a research assistant at Six Nations Polytechnic’s Deyohahá:ge: Indigenous Knowledge Centre, gifted our small group with the teaching of Todadaho, which quickly became a reference point for our discussion.

“Long ago, there was a male child abandoned and left for dead,” Gibson explained. “As he learned to walk from the animals, they say he had seven crooks in his body. Snakes stuck out of his hair as a sign of the negative mind and bad thoughts. His mind had been corrupted by the negative experiences in life and [he] could not see the good. Death and despair was the sign of Todadaho.”

Although grief transformed Todadaho into a threat to peace between nations, a Huron man called the Peacemaker eventually sought him out. “The Peacemaker spoke to Todadaho, and with his helper, Hayehwatha, began healing him by first straightening out his body and removing the seven crooks,” Gibson said. “Next they combed the snakes out of his hair.”

“They were able to restore and heal Todadaho into a human being filled with compassion,” Gibson recounted. “Instead of punishing Todadaho for his old ways, the Peacemaker changed the way of Todadaho’s thinking and people were able to see him as a person.”

The lesson is not about punishment, but about the healing that comes from a connection to each other. As settlers, we must straighten our broken bodies and our broken treaty relationships by listening to our host peoples tell their stories of grief and hope. These stories then turn to action, as together we work out what comes next.

The weekend was spent meeting our neighbours and eating fresh pieces of bannock. It was spent bearing witness to places of violence and laughing as we were taught to dance. Most importantly, it was spent reminding each other that under the Creator, and under the treaties we signed, we are all members of one family: a family now called to relate the stories of our past and to ensure different ones for our future.

Originally from Ottawa, Ally Siebert, 22, now attends Stirling Avenue Mennonite Church in Kitchener, Ont., one of the churches involved in organizing the event.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.