The Mennonite more-with-less ethic is something I have always connected with. Shopping for clothes at the thrift store, commuting by bicycle and eating simple, tasty food are practices that have defined my life in the Mennonite community. These values ultimately steered me toward work in environmental policy, and today I work at one of the largest environmental research organizations in the world.

In my mind, simple living aligns with what I see as an urgent need to address environmental destruction. But, ironically, in the realm of mainstream climate policy, more-with-less could hardly be more foreign.

In my day job, the assumed economic context for our work is limitless growth and endless consumption. Though this overconsumption of material resources is driving environmental destruction, it is not questioned.

Gross domestic production

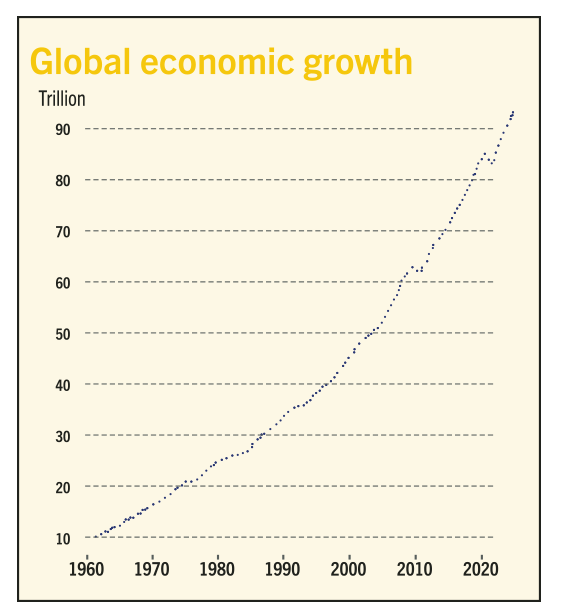

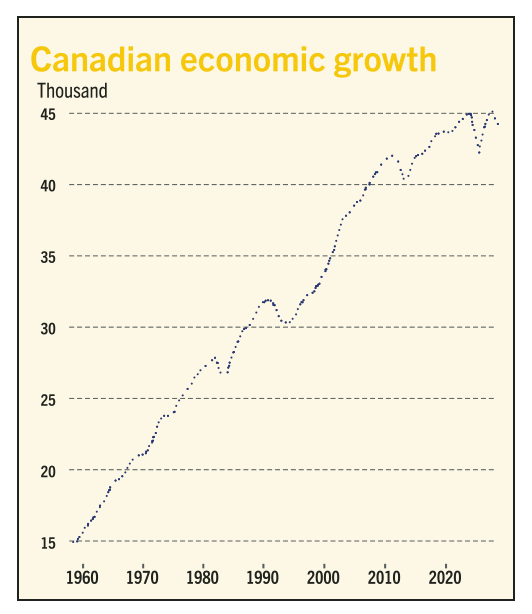

Most governments aim to have their economies grow by approximately two to three percent each year. This is relentless growth, and it means that the size of the economy doubles every 20 years.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of the total value of goods and services produced in a country or region. In 2020, global GDP was twice as large as it was in 2000. And in 2000, it was twice as large as it was in 1980, and so on.

The current plan is for this economic growth to continue, without stopping, forever.

Every time the economy doubles, the quantity of resources we consume more or less doubles as well. Since 1900, the amount of material resources we produce—mostly plastic, concrete, bricks and metals—has doubled every 20 years.

It’s a more-with-less nightmare.

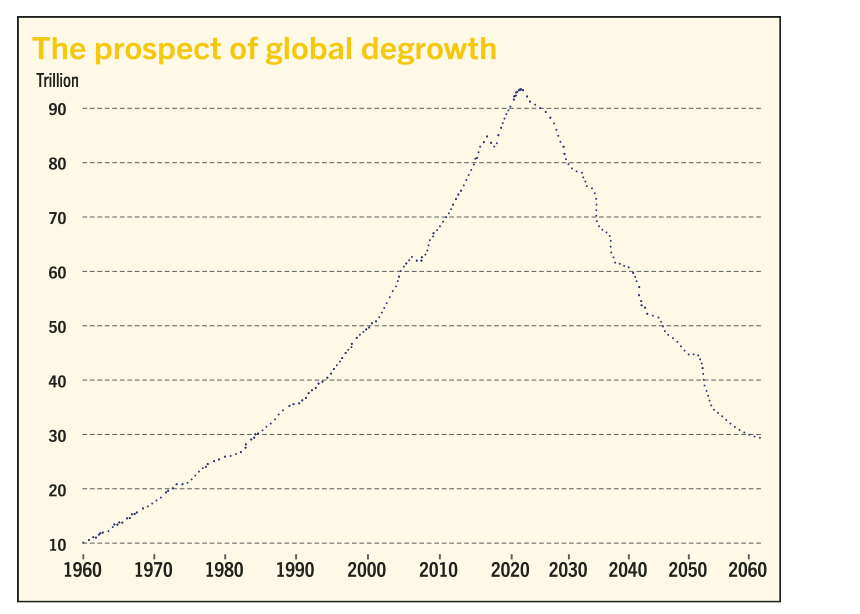

This has implications for the climate. The relevant question is whether we can keep doubling the size of the economy and also dramatically reduce our emissions. Can we maintain economic growth and still hit net-zero emissions by 2050?

The answer is clearly “no.”

Using the federal government’s definition, net-zero emissions is the point at which “our economy either emits no greenhouse gas emissions or offsets its emissions, for example, through actions such as tree planting or employing technologies that can capture carbon before it is released into the air. This is essential to keeping the world safe and livable. ”

More than 140 countries have pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Limits

To avoid environmental destruction, we need to think differently about economic growth.

In fact, we need to think about degrowth. The more-with-less ethic that organically grew out of Mennonite involvement around the world is consistent with this. Doris Janzen Longacre’s Living More with Less, written in cooperation with Mennonite Central Committee and published in 1980, expressed serious concerns about the impact of economic development on our global community.

Data source: World Bank

While Janzen Longacre’s well-known More-with-Less Cookbook provided many simple recipes for families interested in eating ethically and minimizing waste, Living More with Less served as a kind of philosophical text that reflected on scripture and global development to offer suggestions on how to live out Christ’s call in an unjust world.

The book encouraged North American Mennonites to embrace a philosophy of simple living in response to resource inequality. “To live as most of us do in North America, then to study world poverty and our role in it, and to come away without seeing a need for forgiveness and change—that is unthinkable,” she wrote. The book argued that we as a church should live in a way that reflects a concern about global issues and thus reduce our consumption.

The book discusses local food production, reusing materials when possible and slowing down to enjoy time with family. Janzen Longacre explained in clear and common-sense language that the thoughtless consumerism promoted in our economies hurts the environment, exploits people living in poorer countries and negatively impacts our own lives. The book’s title captures the idea nicely—we can live more fulfilling lives by consuming less.

The more-with-less ethos shows that Mennonites had been educating themselves and responding to the difficult political and environmental injustices created by the global economy. More-with-less fit with the original school of environmental thought and, in some ways, Mennonites were ahead of their time. Mennonite discussion around reducing consumption reflected many of the ideas of the early environmental movement. The Limits to Growth, published by a team of prominent researchers in 1972, warned of the impact of unchecked economic growth on the planet. The UN’s 1987 Brundtland Commission encouraged humanity to separate our needs from our felt wants and scale back consumption among the rich. Janzen Longacre’s book fit with these themes.

Sustainable growth?

However, over the years, the idea of reducing consumption fell out of fashion in the environmental movement. In its place, innovation and technology have taken over mainstream environmental policy. The concept of sustainable development has become the world’s major environmental policy framework. This approach seeks to accommodate rather than confront the concept of endless economic expansion.

Most climate policy today is invested in the narrative that we don’t have to change our lifestyles in order to reach our climate targets. We are not told to buy less but to buy carbon offsets. Instead of driving less, we can purchase new electric vehicles. Instead of re-thinking our lifestyles, we can wait for scientists to invent carbon capture technology.

Technology will solve all our problems, we are told. We do not need to shrink our economies or lifestyles. This has produced some serious problems.

What is concerning about our path away from more-with-less environmentalism is that our techno-solutions have not been effective: carbon offset programs have consistently revealed themselves to be scams, electric vehicles may reduce some emissions but depend on other kinds of environmental damage, and carbon capture technology literally does not work.

A quote from John Kerry, the U.S. special presidential envoy for climate from 2021 to March 2024, reveals how far down the wrong path our environmental policy has wandered: “I am told by scientists that 50 percent of the reductions we have to make to get to net-zero are going to come from technologies that we don’t yet have.”

Far too many of the solutions proposed by environmental policy leaders amount to saying: “scientists will figure this out later.”

The idea of simply consuming fewer resources appears to be unthinkable.

Given that we’ve gasified 2 trillion tons of carbon, literally changed the chemical composition of the sky, and set ourselves on track to kill the only planet known to sustain life, it would be nice to see one sentence in a net-zero report about how we’ve gotten into such a terrible crisis.

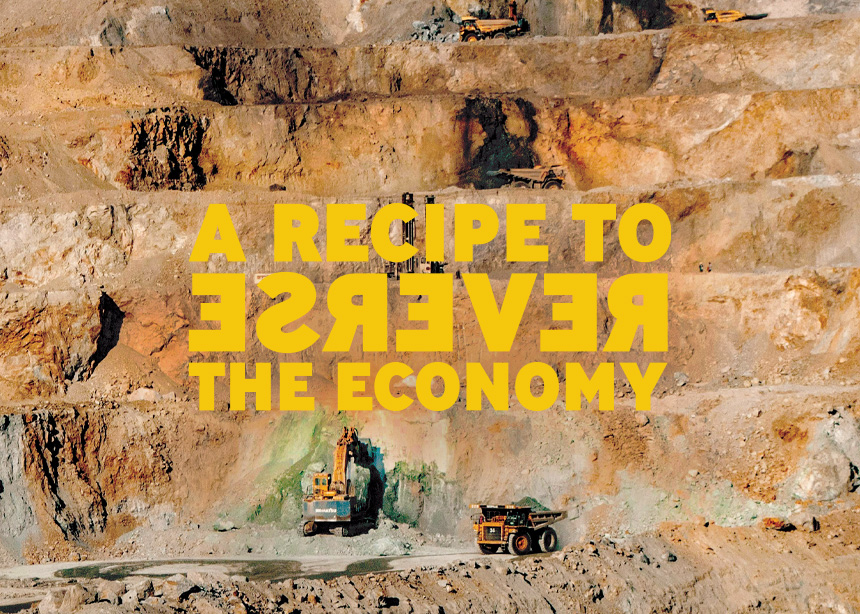

Renewable problems

Even though new renewable energy technology can be exciting, there are still many issues with the clean energy transition that do not receive the attention they require. Mining of clean energy minerals, for example, disproportionately hurts marginalized communities, can be destructive for biodiversity, and also uses a lot of fossil fuels. The International Energy Agency’s analysis indicates that we need six times more mineral inputs compared to today in order to reach net-zero by 2050.

Demand for lithium, for example, is expected to grow to more than 40 times the current level. This will require a stunning increase in mining. Many intelligent researchers question whether it is actually possible to mine that quantity of minerals.

Mining is not the only problem. Questions around energy efficiency also need to be taken far more seriously. It is often assumed that making things more efficient will reduce energy demand but energy efficiency often leads to people using more energy because costs are reduced. For example, people tend to buy an excess of energy-efficient light bulbs. At the end of the day, more advanced renewable technology is not relevant if we constantly keep using more and more.

The economic climate

Many people probably don’t understand that climate change policy is not written by climate change scientists or environmentalists. Instead, governments generally get economists to craft their climate policies.

Economists do not generally spend their time envisioning a more just and sustainable world. Instead, they create climate change policy by mathematically switching over our current energy system to one based on renewables. For example, they use computer models to determine how much mining is required to reach specified targets but not how realistic or damaging the required mining might be. These models sidestep the downsides of new technologies. They use calculations that assume endless economic growth is both possible and desirable.

There’s a broader philosophical question here: why does the flourishing of human economies depend on the annihilation of the living world?

And, as Janzen Longacre might ask, does all the growth and consumption in the developed world actually lead to meaningful life?

The beauty of degrowth

Degrowth provides another way to think about these big questions. Degrowth is about building an economy that respects natural limits while investing in human well-being.

The climate policy ideas I find most exciting comes from people who imagine a beautiful future. This is something Living More with Less shares with the most impressive environmental literature today. For example, there are many different ways we can produce large amounts of food without conventional fossil fuel agriculture. Ideas from permaculture and smallscale farming show much potential but are rarely taken seriously in mainstream environmental policy.

We can also think more creatively about urban design. Instead of creating isolated suburbs, we could design comfortable neighbourhoods that are integrated with local food systems, walkable spaces and super-efficient buildings. Many countries around the world have designed communities like this. Such places produce fewer emissions, foster healthy communities and are nicer places to live. This is a more-with-less kind of world, where we are happier and healthier as we use less of the world’s resources.

The more-with-less ethic is more relevant today than it ever has been. Spiritually, we must consider our responsibility as Christians living in an unjust world. Our world is sacred and we have a responsibility to care for it.

From an environmental perspective, it is clear that the overconsumption of resources promoted in mainstream society is not compatible with our climate targets. It turns out that using fewer resources is not just spiritually important, it’s the only way to prevent environmental catastrophe! More-with-less could be the key to digging ourselves out of crisis.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.