In order to address a $265,000 deficit, Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT) will close its Winnipeg-based Indigenous Peoples Solidarity team at the end of March. While CPT hopes to maintain relationships with its Indigenous partners, three full-time and one half-time positions devoted to the work will end.

CPT teams in Columbia, Palestine and Iraqi Kurdistan will also experience cuts, but not closure. The CPT Europe regional group also works on the Greek island of Lesvos, a key stop-off for people fleeing Syria and other places.

The cuts will help ensure the organization’s sustainability, according to spokesperson Caitlin Light. The deficit is the result of a major grant not coming through at the anticipated level, as well as increased stipend costs and a slight drop in donations.

CPT’s overall annual budget is in the range of $1.3 million, with 18 full-time positions and 10 part-timers. About 10 percent of CPT support comes from Canadian donors, with the bulk coming from the United States.

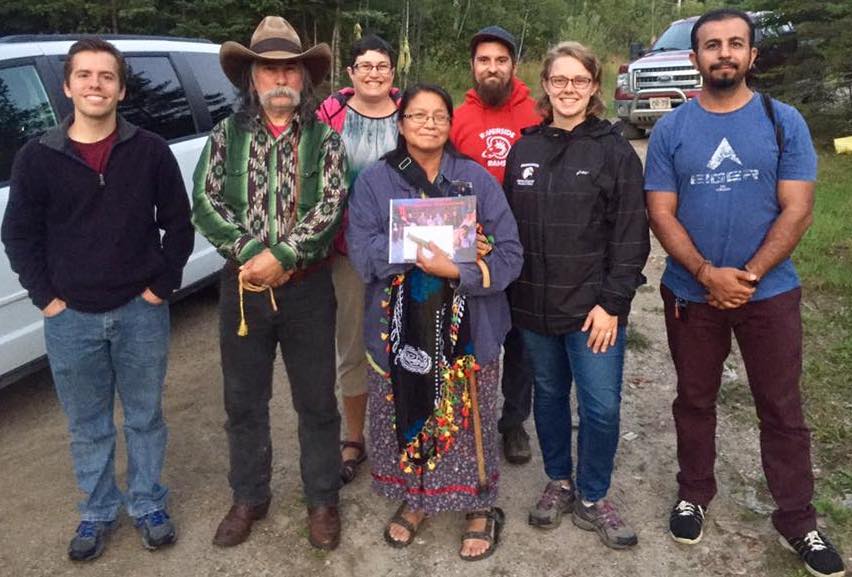

CPT’s Indigenous Peoples Solidarity (IPS) work grew out of a 2002 invitation from the Asubpeeschoseewagong (Grassy Narrows) First Nation, which was blockading logging trucks northeast of Kenora, Ont. While the relationship with Grassy Narrows has remained key, the work has expanded to include support for Shoal Lake 40 First Nation and public education work in Kenora and Winnipeg.

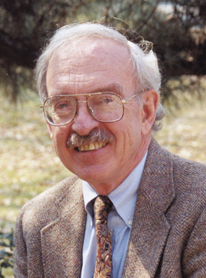

CPT’s origins date back to a speech by Ron Sider at the 1984 Mennonite World Conference, in which he called for a willingness to die in “nonviolent attempts to reduce conflict.” (See an excerpt below.)

Since 1988, CPT has put people of faith in places of overt conflict, often accompanying people who face threats of violence. The work has shifted partially to building relationships with partners and supporting them.

CPT’s profile skyrocketed in 2005, when four of its workers were kidnapped in Baghdad. One of the four, American Tom Fox, was killed; the other three were freed by British and Canadian special forces after 118 days in captivity.

Doug Pritchard was co-director of CPT at the time. He says CPT experienced a temporary spike in donations for a year, but no increase in people signing up to join. The organization had grown rapidly from the 1990s until the kidnapping, but after the brief spike in contributions, the previous growth trajectory flattened out.

Pritchard, who was with CPT until 2011, worked hard at maintaining ties with Mennonites across Canada. He says that over time the organization devoted energy to wrestling with factors beyond Sider’s original challenge of bold peacemaking. Those explorations, Pritchard says, “revolved around power dynamics, including racism and sexism, within CPT,” an organization “founded largely by white men.”

The historically strong ties with Mennonite Church Canada have waned. While MC Canada still appoints a member to the CPT Steering Committee, it no longer handles donations for CPT or issues tax receipts, as it used to. The two organizations signed a partnership agreement in 2010, but after a change in staff at MC Canada, the church ended its financial relationship with CPT in 2015.

The hostage incident highlighted a potentially related point of dissonance between the two. One of the freed CPT hostages, Jim Loney, came out publicly as gay upon his return to Canada. CPT had previously kept this fact hidden, for Loney’s safety. Although MC Canada never stated it openly, this highlighted a difference between the two organizations.

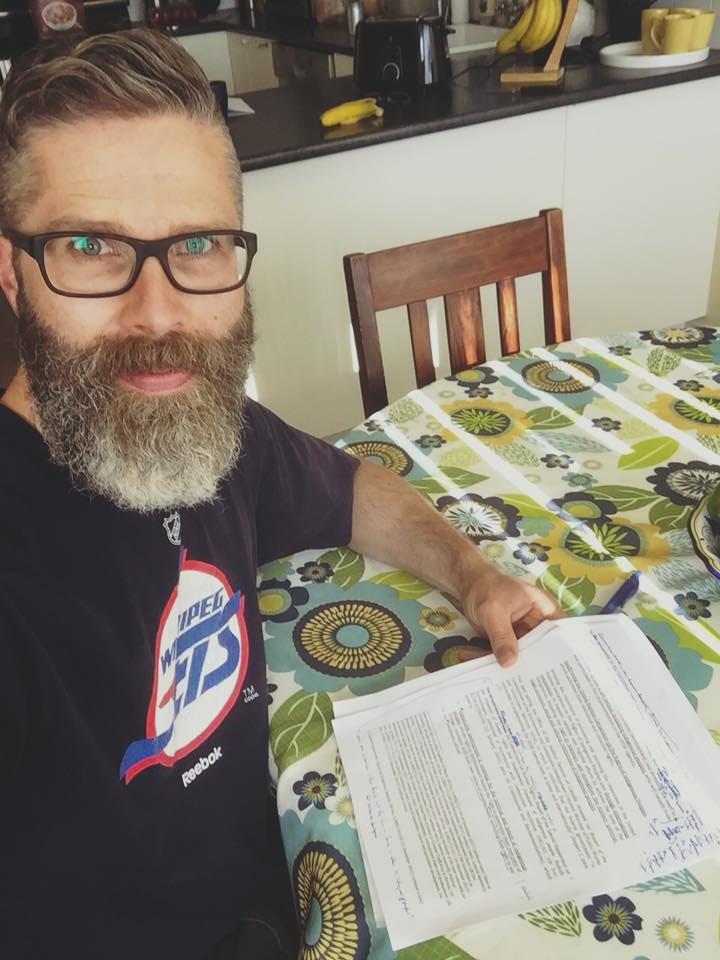

The key link between the two now is Steve Heinrichs, MC Canada’s director of Indigenous-Settler Relations, and its appointee to the CPT Steering Committee. Prior to joining MC Canada, Heinrichs had served with CPT in Palestine for a half-dozen four- to six-week stints. In his current role, he has worked very closely with CPT’s IPS team, largely on public education around the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Heinrichs has high praise for CPT, calling the organization “a great partner and great friend.” He expressed “deep grief and sadness” over the closure of the IPS team.

The larger conversation, he says, is “where CPT is at in relation to the church.” For him, the gift of CPT is its expression of the peacemaking gospel within the context of community. Not only does it take an “active non-violent posture to the bruised and battered in the land,” but it wrestles with how to partner and work with people of other faiths, how to work well in Muslim countries, and how to genuinely partner with Indigenous people who are not Christians. Heinrichs sees this as an instructive, prophetic example for the church at large.

In terms of work with Indigenous peoples, he says the commitments the churches have formally made, going back to 1987, will require us to enter zones of conflict in peaceful ways. CPT is one group that can help with this, though, of course, its capacity in Canada is now minimal.

CPT is committed to maintaining relations with Indigenous partners to the extent the Canadian coordinator Rachelle Friesen can do so, and it hopes CPT reservists can be deployed if requested.

Caitlin Light invites more Canadians to become CPT reservists, something that requires a month-long training and 2-16 weeks of service per year over a three-year term.

Sidebar: Ron Sider’s perspective

“Over the past 450 years of martyrdom, immigration and missionary proclamation, the God of shalom has been preparing us Anabaptists for a late twentieth-century rendezvous with history. The next twenty years will be the most dangerous—and perhaps the most vicious and violent—in human history. If we are ready to embrace the cross, God’s reconciling people will profoundly impact the course of world history. . . . This could be our finest hour. Never has the world needed our message more. Never has it been more open. Now is the time to risk everything for our belief that Jesus is the way to peace. If we still believe it, now is the time to live [out] what we have spoken.

“We must take up our cross and follow Jesus to Golgotha. We must be prepared to die by the thousands. Those who believed in peace through the sword have not hesitated to die. Proudly, courageously, they gave their lives. Again and again, they sacrificed bright futures to the tragic illusion that one more righteous crusade would bring peace in their time, and they laid down their lives by the millions.

“Unless we . . . are ready to start to die by the thousands in dramatic vigorous new exploits for peace and justice, we should sadly confess that we never really meant what we said, and we dare never whisper another word about pacifism to our sisters and brothers in those desperate lands filled with injustice. Unless we are ready to die developing new nonviolent attempts to reduce conflict, we should confess that we never really meant that the cross was an alternative to the sword….”

—Ron Sider, at the 1984 Mennonite World Conference, in a speech that inspired the creation of Christian Peacemaker Teams.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.