No one saw it coming. Not family, not friends, not anyone at the university he attended. On March 23, 2018, after babysitting his nieces and nephews, 18-year-old Nicholas (Nick) Penner Brandt returned to the apartment he shared with an older brother and twin sister, drank poison and died.

In one horrible instant, the entire Brandt family was thrown into a chaos of wrenching grief and unanswerable questions. Nick’s father Randy expresses how incomprehensible his son’s suicide was: “If the evidence wasn’t there, and if he hadn’t left a note, I would have looked for a different explanation.”

There were no obvious indicators that Nick was in trouble. No one could have seen it coming, and the questions, “what-ifs” and the resulting unwanted life changes have no visible end.

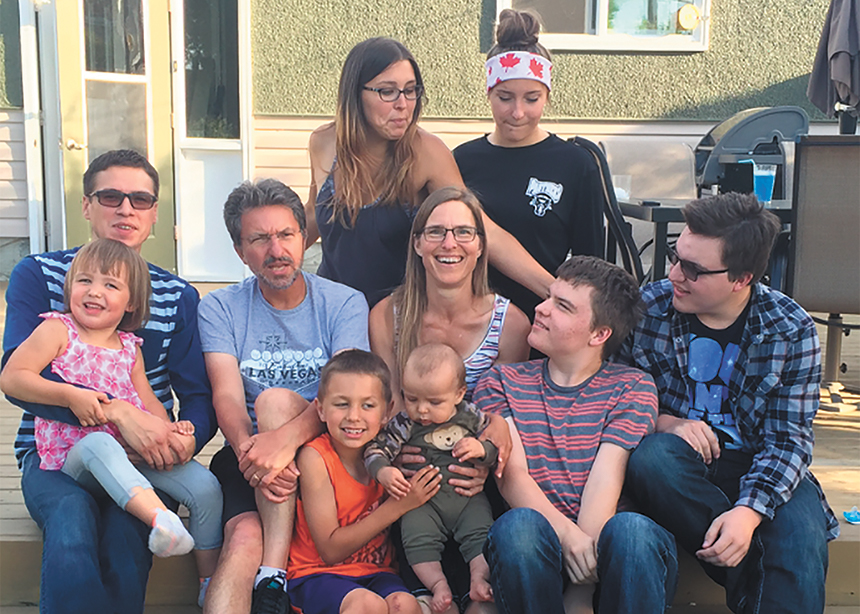

To all outward appearances, Nick’s life was normal, perhaps even charmed. Good looking, intelligent, gentle, funny and uncomplaining, he had many friends and strong family relationships.

In the fall of 2017, he began a computer science program at MacEwan University in Edmonton. His activities included reading, skiing, and playing board and video games. He enjoyed family vacations.

Like many introverted personalities, he was often quiet. There were no changes in behaviour that might have indicated depression or mental illness. The note he left for his family let them know that he loved them but that his experience of life was too hard to continue. He related not having felt emotions for four years, and that ending his life was not a rash decision but a carefully planned choice. This was no mistake or cry for help. It was a firm and well-researched decision that he did not share with anyone else.

A funeral was held at First Mennonite Church in Edmonton on March 31. In planning for the service, the Brandts were united in their desire to be open about what had happened, for their own coping and to possibly be of help to others. In the days and weeks after the service, many have thanked them for this. It has encouraged conversations and challenged the stigmas and silence that can surround suicide.

“Why? Why didn’t he say something?” Randy and his wife Susan have asked this question over and over, knowing there is no answer for them. Their story, however, might give someone else the courage to say something, it may provide the nudge to prevent the tragedy of suicide in another family.

Overcoming the stigma

In the recent past, suicide was regarded as both a crime and a sin, but Randy and Susan never considered trying to hide what had happened. “We didn’t know that it was supposed to be secret. . . . I can’t imagine the horror of trying to hide something like that,” Randy says.

Their experience indicates that perhaps past stigmas attached to suicide are changing. “No one has said anything even mildly judgmental,” he says.

“The church was so incredible. We really felt held and loved by them; they embodied love in action. They took such a load off our shoulders. That was huge,” Susan adds.

Even though the stigma may be less powerful than it used to be, there are still negative legacies associated with suicide. While intellectually it is possible to know there is no blame to be had, the heart is not easily convinced.

Susan expresses the struggle, saying: “The feelings of shame do come. It feels like we have been handed the ultimate Worst Parent of the Year Award. . . . Maybe a part of me is embarrassed that we have this in our family. Weirdly, it is a real blow to your ego on top of the tragedy.”

Coping with new realities

The Brandts don’t feel they have gained any special wisdom from their loss. However, they have noticed that many people are awkward around them, and in not knowing what to say, they avoid acknowledging the family’s ongoing loss, or they attempt to cheer the family up. When, for them, every waking moment is a reminder that Nick is gone, avoidance and cheeriness are not helpful.

“In talking to people who deal with tragedy, I have learned not to practise avoidance,” Randy says. “It feels good when people acknowledge the pain.”

Adds Susan, “I crave hearing about Nick.”

Susan shares how Nick’s death has put stress on the whole family system. “It has been really hard on our relationships, even though we haven’t fought,” she says. “We are missing him. He was a ‘middle man’ who could diffuse situations with a joke. The family dynamics are completely different. It puts stress in the whole family system.”

Since each family member might need space, togetherness, tears or laughter at different times, these needs inevitably cause friction when no one has any emotional reserve. Being at a child’s birthday party, as an example, is necessary and joyful, while at the same time it is a painful trigger for fresh bouts of grief. “Grief is so fragmented,” Susan observes.

In the midst of the pain, some things are sustaining and helpful. Counselling services and a suicide survivors group provide important support, and Susan finds that reading about the aftermath of suicide is helpful in dealing with thoughts and feelings that seem dark and overwhelming. “There is no new thought under the sun. [Knowing this] is very validating,” she says.

Practical help in the form of the old-fashioned bringing of casseroles and numerous small kindnesses have helped to sustain the Brandts.

“Never minimize what you have to offer,” Susan says. “We have felt support from places we never expected. I hope I never feel that I am not close enough to matter.”

The Brandts’ struggle with the questions and repercussions of Nick’s choice will continue. The same questions will need to be asked over and over in the process of learning to cope with the reality of loss. While no one saw this tragedy coming, perhaps the sharing of their story can bring other silent struggles into the light of hope and help.

More on mental health:

‘Acceptance without exception’

Meeting the mental health needs of students

‘Poetry and art for mental health’

Resilience Road leads to mental health for women

From church to yoga studio

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.