In 2004, Joachim Wieler of Weimar, Germany, opened a small wooden box he inherited after his mother’s death. To his surprise and horror, it contained letters his late father wrote while serving as an officer in the Wehrmacht, the armed forces of Nazi Germany.

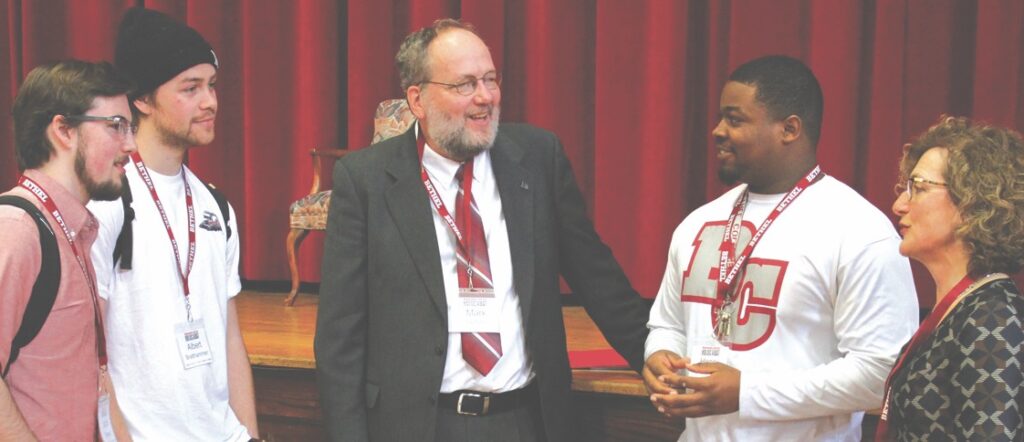

“I almost fell off the chair,” Wieler said, speaking to more than 200 people at a conference on Mennonites and the Holocaust on March 16 and 17 at Bethel College.

Writing from France in 1941, at the height of the Nazi conquest of Western Europe, Johann Wieler wrote: “We did not believe we would bring the French to their knees in such a short time. All soldiers who are fighting here for their fatherland are performing worship in the truest sense of the word. Those who do not believe in our victory do not believe in God. The Lord is visibly on our side. Heil Hitler.”

While his father fought on the western and then eastern fronts, young Joachim Wieler saw Dresden burning and wound up in a refugee camp, where the family received help from Mennonite Central Committee while Johannes languished as a prisoner of war in the Soviet Union until 1949.

But it would be 60 years before Joachim Wieler discovered his father had celebrated Nazi aggression as the fulfillment of a divine plan. “Probably a lot of boxes still exist somewhere,” Wieler said of probing the secrets of the past.

Uncovering hidden stories of interactions between Mennonites and Jews during the 1930s and ’40s in Europe was the purpose of the conference, which drew scholars from the United States, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and Ukraine.

The event was the third of its kind—following ones in Münster, Germany, in 2015, and Filadelfia, Paraguay, in 2017—to examine Mennonite complicity in the militant nationalism and racism that produced the Holocaust and to ask if anything like it could happen again.

Twenty presenters described their research, which extended across the spectrum of wartime horror and mercy, from Mennonite participation in Nazi atrocities in Ukraine to hiding Jews in the Netherlands.

Steve Schroeder, who teaches at the University of the Fraser Valley in British Columbia, described the failure of Mennonites to acknowledge their anti-Semitism and support for National Socialism under Hitler—whom many viewed as a German saviour—as a denial of the past that can be corrected only by truth telling.

An honest probing of the past can be intensely personal for Mennonite scholars like Schroeder. He told of interviewing his own relatives who had lived in Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) and celebrated that city’s incorporation into the German Reich.

Although more than half a century had passed when Schroeder conducted the interviews, he said those he talked to “did not process critically their collusion with wartime Nazis, nor did they take a contrite position toward the past.”

One man remembered singing anti-Jewish songs with phrases like “hack off their arms and legs; get them out.”

Such chilling stories “should matter to us,” Schroeder said. “This is our heritage, a heritage that impacts our personal makeup and our engagement with the people around us. . . . Truth telling is a fundamental first step, as is the accompanying act of listening to those who have been harmed, including those who have been harmed by us.

“In my view, a healthy way forward is to acknowledge that Mennonites have not only suffered but have also caused harm, and to address immediate colonial enterprises in which we have participated. I see the seeds of this taking place at this conference, which is encouraging.”

Massacre in Ukraine

When Mennonites and Jews were neighbours in Nazi-occupied territories, many Mennonites welcomed the German regime, and some collaborated with it.

In a session on “Mennonite-Jewish Connections,” two Canadian scholars—Aileen Friesen of Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo, Ont., and Colin Neufeldt of Concordia University of Edmonton—told of contrasting Jewish and Mennonite fates.

Early in the spring of 1942, Friesen said, Nazi occupation forces ordered the Jewish population of Zaporizhia (Zaporozhye), Ukraine, to gather, supposedly to be relocated for work. Men, women and children were stripped, led to a ditch and mowed down with machine guns. The massacre lasted three days. When it was over, 3,700 Jews had been murdered, their bodies carelessly covered in shallow, mass graves.

Local police took part in the atrocity. Eyewitnesses reported that among them were two Mennonite brothers, Ivan and Jacob Fast.

Less than a month later, a few miles away on the other side of the Dnieper River, the Mennonites of Chortitza gathered to celebrate Easter. The Nazis had reopened the churches after years of Soviet repression. This would be the first Easter service in more than a decade. The congregation was filled with excitement. Under German rule, life for German-speaking Mennonites might return to normal.

“These two events force us to confront the realities of occupation,” Friesen said. “During this period, Mennonites would gather to worship, celebrating their freedom to praise God, while their Jewish neighbours were humiliated, stripped of their humanity and gunned down.”

While there is evidence of collaboration and perpetration, Friesen said that the most common response was inaction. “Many did nothing in the face of overwhelming violence,” she said. Famine and terror under the repressive hand of Soviet Communism had shaped their character. The Nazis not only delivered them from the yoke of Stalin but treated them with favour due to their “racial purity.”

“It is hard to find examples of rescue or aid given by Mennonites to persecuted Jews,” Friesen said.

Jews out, Germans in

Colin Neufeldt described Nazi collaboration by the people of Deutsch Wymyschle, Poland, a mostly Mennonite town of 250 to 400 people, against the neighbouring town of Gabin, with a population of 5,700, about half of them Jews. After the Nazi invasion of Sept. 1, 1939, Jews were rounded up and their property confiscated. Mennonites from Deutsch Wymyschle took advantage of the Nazi desire to move the Jews out and the Germans in. They accepted the invitation to claim houses and businesses confiscated from the Jews. Among them were Neufeldt’s grandparents, Peter and Frieda Ratzlaff.

One prominent collaborator was Erich L. Ratzlaff, who became a Mennonite Brethren leader in Canada and edited the Mennonitische Rundschau newspaper from 1967 to 1979. Ratzlaff became the burgermeister, or mayor, of Gabin. Neufeldt said his grandmother remembered that she often saw him walking around with a whip, and Jews had to bow to him.

Another type of collaboration was developing intimate relationships that linked Mennonite families to Nazi culture.

“Deutsch Wymyschle women tied their futures to the Nazi regime when they married non-Mennonite and Mennonite soldiers in the German Wehrmacht,” Neufeldt said. “Weddings were often performed in the MB church in Deutsch Wymyschle in military uniform.”

When the Wehrmacht started drafting Deutsch Wymyschle men, they went willingly. “The principles of pacifism and nonresistance were not strongly emphasized” in their churches, Neufeldt said.

Showing 1940s pictures of men in German military uniforms, Neufeldt noted their demeanor: “Most of these people are my relatives, and they wore the [Nazi] uniform with pride.”

Hiding a Jewish baby

Alle Hoekema of Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam shared stories of Dutch Anabaptists who helped hide Jews from the Nazi authorities. Some 40 of these have been honored by Israel as “righteous among the nations,” although “40 is not a great amount,” Hoekema said.

One woman, Geertje Pel-Groot, took a Jewish baby, Marion Swaab, into her home while the baby’s parents hid elsewhere. Later, a neighbour turned Pel-Groot in to the authorities. She was arrested and sent to Ravensbruck, a Nazi concentration camp, where she died, lauded by other prisoners for her selfless behaviour. Pel-Groot’s daughter took care of the baby, who survived the war.

Mennonite war criminals

David Barnouw of the Dutch Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies spoke about Dutch Mennonite war criminals who escaped prison and immigrated to Paraguay. One of these, Jacob Luitjens, later emigrated from Paraguay to Canada and was part of a Mennonite congregation in Vancouver, B.C.

Barnouw said that during the Second World War, Luitjens was an active collaborator with the Nazis and worked on propaganda. After the war, he gave himself up to the police because he feared reprisals from members of the Dutch resistance. Luitjens changed his name to Harder.

In 1991, the Netherlands sought to extradite him to be tried as a war criminal. Although many Mennonites supported him, a Canadian judge ruled that he got his citizenship illegally and he was sent to the Netherlands, where he was taken to a prison. He was set free in 1994, when he was 74. He was the last Dutch war criminal to be tried.

Breaking the myths

The personal connection is what drew Doris Bergen, who holds the Chancellor Rose and Ray Wolfe Chair in Holocaust Studies at the University of Toronto and gave the conference keynote address, to begin looking specifically at how Mennonites were affected by and involved in the Holocaust.

As a young scholar studying Nazi Germany, she was taken aback to come across a Martens (her mother’s family name) from the Russian Mennonite colony of Einlage (her place of origin).

One challenge, which came up at several points during the conference, is how to define “Mennonite.” Bergen’s bottom line: While a functional definition is important, “resist the temptation to define to distraction,” thereby obscuring the real issues of genocide, racism and anti-Semitism.

Bergen noted the oft-forgotten groups in the Holocaust narrative: the disabled, the Roma, Soviet prisoners of war, Polish civilians. At the same time, there should be “a clear focus on the Jews’ particular place in the Nazi plan of destruction,” she said.

She said the scholar’s job is “to break apart the myths. . . . Many groups are confronting and breaking the myth of their own innocence or non-complicity in the Holocaust. This can be enormously liberating,” she concluded.

Gordon Houser of The Mennonite and Melanie Zuercher of Bethel College contributed to this report. From Mennonite World Review. Used with permission.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.