The ongoing discussion about medical assistance in dying has publicly raised questions that extend beyond the realm of politics and public policy to the bedrock of morality.

Should the intentional killing of a person ever be legal? If so, under what circumstances? Do people who face a life of severe pain deserve the right to end their lives? How do we as a society balance personal autonomy and respect for life? Do people who have decided to end their lives deserve the opportunity to do so peacefully and accompanied by loved ones, instead of violently and alone? Who should get to decide all these things? And how can we talk about such impossibly sensitive matters in a way that honours the deeply personal experiences of all?

Rod and Susan Reynar raise a further question for people of faith: What does community mean for us in the face of suffering?

While most of us carry deeply personal experiences relevant to medically assisted dying, the Reynars’ experience is particularly stark. Due to a congenital condition compounded by a medical error years ago, Rod lives with constant excruciating pain. “Even at my best times, there’s rarely some time in the day when I think, ‘I just can’t do this,’”he tells me via Skype. “Then there are times when things get worse.”

He will live the rest of his life in pain. One doctor said his condition is like experiencing terminal cancer but with no end in sight. “That comes as a daily challenge to me,” he says quietly.

This is after receiving an implant that reduced his pain significantly. The device, installed by a doctor in the Netherlands, uses electrical impulses to his spine to ameliorate the pain. Before that, he spent over 12 years bedridden, his dream career as an academic gone, and his participation in the life of his two young daughters reduced to them eating meals with him in his bedroom. Every breath was torturous. Conversation took immense effort. He lived life in 10-minute increments. Most, although not all, people who came to visit him were too overwhelmed to return.

More than once during that period he planned his own death. In a Mennonite Church Canada podcast he explains how, on one occasion when his wife Susan observed that something was amiss, she pushed him until he confessed that he had decided to die and knew how he would do it. “She backed me in the corner,” he recounts. She said defiantly that if she and their daughters weren’t reason enough to live, then he should go ahead. He didn’t.

His point is about how we are not just our own, but that our identities are also held by others. In some sense, he didn’t have the right to decide unilaterally to end his life.

Personal autonomy . . . or not

That stands in contrast to federal Health Minister Jane Philpott, a member of Community Mennonite Church in Stouffville, Ont., who has said of the Liberal government’s medically assisted dying legislation: “First, it is about the principle of personal autonomy.” She was unavailable for an interview.

The Reynars insist that people are not merely autonomous individuals. But they are not just talking about who gets to decide about death, they are calling the church to take up the responsibility to walk closely with those who suffer and those who are dying. They focus not on how to answer ethical questions, but how to walk with those who suffer.

Rod says we have “lost the art of suffering.” He testifies to the need for vulnerability and “an openness to explore that which is shrouded in mystery and uncertainty.” How can we nurture the capacity to walk with those who are suffering or dying? Rod says, simply, that we need to be present to such people and “deeply take them on as our own.” This must be modelled in community.

Susan recalls the image of their teenage daughter climbing into bed with her barely responsive grandfather during his final days, which were lived in the Reynars’ home. She had always liked reading with him, so that's what she did.

She adds, though, that not everyone can sit with a dying person. Some can find practical ways to support people and their families.

Through it all, the movement the Reynars speak of is one toward suffering, rather than away from it.

Nothing redemptive to say about suffering

Jason Reimer Greig, a 2015 graduate of Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary in Elkhart, Ind., writes of the modern medical system as one founded on the notions of self-determination and the elimination of suffering. His recent book, Reconsidering Intellectual Disability: L'Arche, Medical Ethics and Christian Friendship, says that deep relationship ought to be our response to suffering, rather than the impulse to fix the situation.

Our Supreme Court Justices have nothing redemptive to say about suffering. The 2015 Supreme Court ruling that led to the medically assisted dying legislation that was passed by the House of Commons on June 16, 2016, said it is not acceptable to “[leave people] to endure intolerable suffering.”

I asked Rod what he thinks of that wording. His answer headed back to the fundamental value of community. He says that “what stands out” from his toughest times is “how the presence of others made seemingly intolerable times tolerable.”

Still, he says that if a person and his or her community decided it was time to let go of life, he would have a responsibility to “step away” from his “idealistic statements of truth” and trust those who have walked with the person and paid “respect to what the individual is experiencing.”

The Reynars deal more in graciousness than ethical absolutes. It is hard not to notice the phrase “without judgement” dotting their comments.

The ‘best thing’

Novelist Miriam Toews has written about the suicides of her father and sister. In a CBC interview last year, Toews said that her sister, who was tortured by severe mental illness, “begged” Toews to take her to Switzerland, where she could legally and safely end her life.

“I was paralyzed,” Toews said. “It seemed an impossible thing to do.”

Her sister died alone on a train track.

Later, Toews says, she realized that a medically assisted death “would have been the best thing.” Her sister could have died with someone “holding her . . . giving her what she was entitled to have.”

She acknowledges the controversy: “I understand all the resistance to it.”

My friend Dave also died violently and alone. Although he was young, brimming with passion, and loved by many, he could not endure the mental illness that tormented him. With anguish, his friends later recognized that he had systematically spent time with key people before his death, something that must have been an impossibly lonely farewell tour.

‘One or the other’

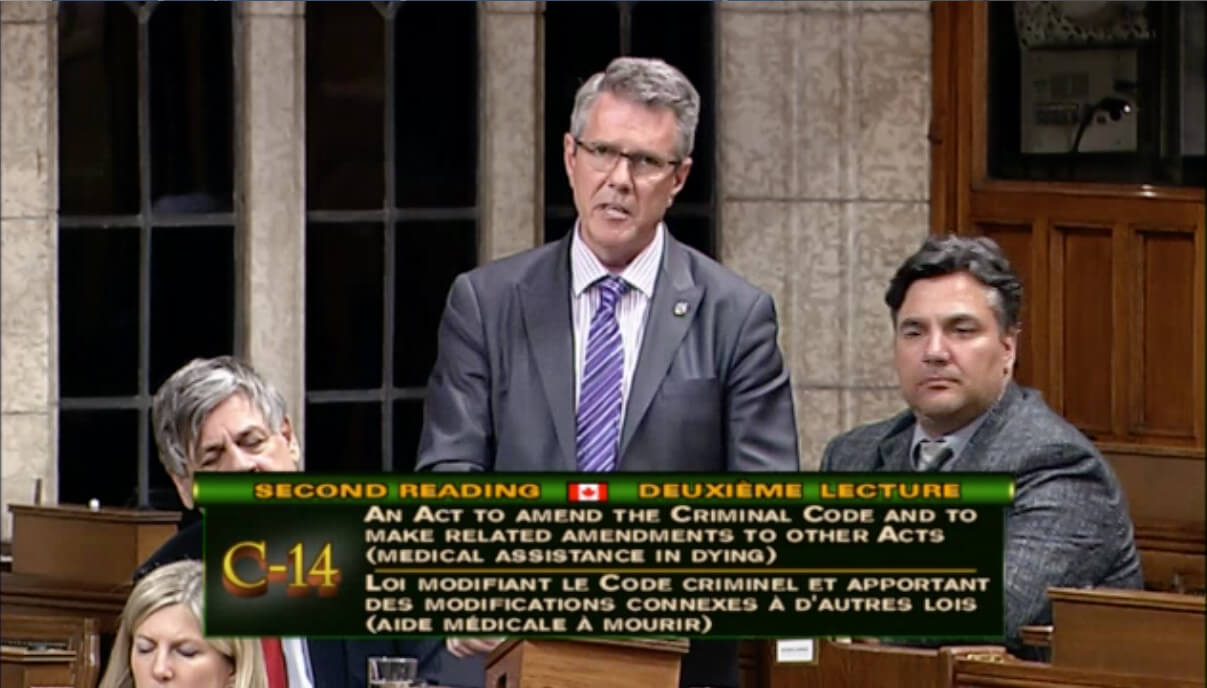

Our country’s new law does not extend to situations like these. It stipulates that medical practitioners will not be criminally culpable if they assist in the deaths of “competent adults” who have “a grievous and irremediable medical condition that causes them enduring and intolerable suffering,” and “whose deaths are reasonably foreseeable.”

The legislation provides various checks and balances to help protect vulnerable people. It also ensures freedom of conscience for medical practitioners not comfortable with medically assisted dying. The government has called for more study on the legally complex matter of advance requests, as well as circumstances involving “mature minors” and instances in which “mental illness is the sole underlying medical condition.” The current law does not apply in these cases.

While the law purports to strike a balance between personal autonomy and respect for life, ethicist Margaret Somerville says that “those considerations can’t be balanced; we have to choose one or the other.” In an email, Somerville—a professor in the faculties of law and medicine at McGill University in Montréal, and presenter of the 2006 Massey Lectures—says the new law is unnecessary and “very dangerous." She believes it will erode respect for life both in specific cases and in “society as a whole.”

Noting a report of 166 “medically inflicted deaths” in Quebec since December 2015—Québec jumped ahead of the Supreme Court and the federal government in this regard—Somerville says this shows that such deaths will not be rare in Canada. She has written previously that assisted deaths ought to occur only in exceptional circumstances and not become the norm.

In response to my question about whether the government has considered or estimated how prevalent medically assisted deaths may become in Canada, a Health Department spokesperson said only that the legislation makes provision for data collection.

Somerville believes the law puts us on an “unavoidable slippery slope, as has already happened in the Netherlands and Belgium.”

‘I value life’

Ironically, the Reynars spoke to me from the Netherlands, where Rod is having adjustments made to his implant. Obviously, he is aware that there he “could be granted authorization” to take his life. “It’s an odd thought”," he says, adding, “I fully understand those feelings, and have had them, where I wanted nothing other than to die. And yet I value life.”

To learn more visiting people with chronic pain, visit bit.ly/tips-for-visits.

See also:

A time to die

Loving life, befriending death

Other faiths speak out on end-of-life issues

‘Right to life does not include the right to be killed’

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.