I still think of myself as a shepherd. Every day, actually every night, I’m out there. I look for the lost, the wanderers and the weary, and I bring them home. It’s a living. At times, it’s easy; they know the way and I just help them along. Other times, it’s dark and cold, and I worry about predators in the shadows. My lost ones might—or might not—be in good shape. Sometimes they are full of good cheer, other times they’re belligerent. Sometimes they turn on me, so I’m always on edge. I have to defend myself even from the ones I’m trying to help. Those are the nights I’m not sure of my new country, the nights I curse the shiny yellow car that is now my office, my vocation, my shepherd’s rod and staff.

When I was a boy, I was almost a traditional shepherd. I was a cowherd: just two cows and their calves. As the youngest in our family, it was my job to find grass and to bring my little herd home at night. Sometimes it was an idyllic job—warm sun, butterflies and birdsong—but mostly it was deadly boring. Occasionally, it was scary. There were snakes hidden in the grass, and people who tried to take my cows. I didn’t like it, but someone had to do this “entry level” job, as I’ve come to call it.

Eventually, I grew up, went to school and found work in the city. Things looked good for me, but that was before the troubles. When the fighting started, I lost my job. The various armies were trying to grab us young men, so I ran into the bush to hide along with a few friends. Soon there was no food, no money and no safe place. Some of us, the very lucky ones, managed to get out and eventually found our way here.

When I came to this country as a refugee, they said my credentials weren’t at the right standards. I need to upgrade before I can get back to my profession, but school is expensive and takes a long time. My family needs to be fed now. So I’m back to a kind of herding: driving a taxi and revisiting my childhood, along with the engineers, doctors and technicians who also have hungry children at home to feed, clothe and shelter.

One night, a cold one during the holidays, I had just finished shepherding some revellers home from their liquid wilderness. I had to stop at the carwash to clean the backseat of my taxi and was feeling sorry for myself. While I washed my hands in the bathroom, a young man approached to ask directions. His English was shaky; he was new to the city and trying to find his cousin’s apartment, where he and his young wife would stay the night. I told him we could look at the GPS unit in my car, but when I saw his wife was very pregnant and their rattle-trap of a car that wouldn’t start up again, plans changed.

I took them straight to the hospital. She was trying to hide her growing discomfort, and her husband kept saying they should go to his cousin’s place. It was hard to argue with him. His accent was strange to me, he was nervous, and I was watching the icy roads and distracted Christmas drivers!

Finally, I realized my passengers were worried that they couldn’t afford the hospital. I tried to assure them it was okay. I’m not sure they understood, but by then we were at the emergency room doors. The nurses whisked the young soon-to-be mother away in a wheelchair so fast that the husband had no choice but to follow.

Happy they were safe, I went back outside and took my car over to the “yellow zone,” to wait for a fare. It was a moonless night and the stars were unusually bright in the cold sky. It was gorgeous, but I was worried about these strangers, my lost sheep. And I kept wondering, too, about things like how many homeless people were freezing, about what my kids were doing at the moment, about if I’d make enough money tonight to buy something nice for my wife. I sat there worrying about what to do, worrying about other new refugees and trying to remember how I managed that first year. The world overwhelmed my thoughts and despair crowded out hope.

Then my worrying was interrupted by a chatty lady who had convinced her doctor she could go home for Christmas Eve. I drove her there, listening to long lists of the extravagant gifts she had bought for what she called “my spoiled grandchildren.” I silently agreed about the spoiled bit when I walked her to the front door of her very large and very empty house. What a strange world.

Soon I found myself back in the hospital parking lot, looking up at the brightly lit windows and wondering if the couple was now a threesome. Was the baby okay? What could a poor taxi driver do?

A van pulled up and a group of brightly clad people burst out, laughing and holding black folders. I knew what they were, and I had an idea. I jumped out of my car, grabbed a few of my fellow shepherds from their cars, and we followed the carollers into the hospital.

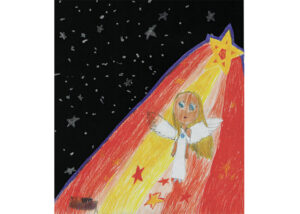

“Hark the Herald,” “Joy to the World,” “Away in a Manger”: they sang them all with angelic voices. We shepherds joined in, unable to remain silent, adding a few rather earthy but enthusiastic tones to the choruses. We sang in waiting rooms, where people with tear-stained faces reacted with smiles. We sang in the common areas and people quit rushing. We sang at the nurses desk, and tired eyes sparkled.

I approached a nurse and asked about the young couple. After a brief phone call, she got up from her chair and came around the desk. The whole bunch of us—taxi drivers and fancy singers—followed her to the maternity ward. We waited outside a small room until she beckoned us in with a shushing finger over her lips. The young couple were sitting together on the bed. When we were all gathered around, a tiny brown face yawned up from where it was swathed in hospital whites. Collectively, carollers, taxi drivers and the nurse all said “Aahhh!” And then we laughed with the new parents.

We sang quietly, while they stroked the child’s face with gentle fingers: “It came upon a midnight clear / that glorious song of old. From angels bending near the earth / to touch their harps of gold. Peace on the earth, goodwill to men / from heaven’s all gracious king. The world in solemn stillness lay / to hear the angels sing.”

With whispered congratulations and Merry Christmases, the carollers tiptoed away. The taxi drivers followed. I stayed for a moment to tell them I would come the next day to take them to his cousin’s apartment. They said thank you and then began to settle in for the night.

It touched me, how, with so much going on, they were at peace. Their hearts were so full for this child, for their new country, for the warmth of strangers. Hope seemed to spill from their eyes and light the whole room. It filled me and chased away the last shadowy bits of worry. Somehow, this was going to turn out.

I caught up to my fellow shepherds in the parking lot. Several were already in a loose circle, digging into coat pockets and wallets. Somewhat comically, a couple others had their bums in the air, searching under seats for loose change.

The collection wasn’t a lot, but it was what we had. It would make a nice gift, a welcome. A thank you for the chance we had to gaze on a miracle and recharge our hearts with hope. After that, I hurried to tell my family all that I had seen and heard this holy Christmas night.

Donita Wiebe-Neufeld is Canadian Mennonite’s Alberta correspondent, co-pastor of First Mennonite Church, Edmonton, and author of Thirty Bucks, a recently released children’s book.

See how the Gingrich family celebrates Christmas in “Christmas: A time for giving.”

For discussion

1. What have been some of your “entry-level” job experiences? Do you think humdrum work provides a better opportunity to listen for the voice of God? Have you ever been surprised by a moment of hope in the midst of what felt like a world of despair? What are some of these sparks of hope that can recharge our hearts?

2. In her story, Donita Wiebe-Neufeld suggests that the cab drivers of today are like the shepherds in the Christmas story. What are the similarities and differences between shepherds and cab drivers? Is this comparison helpful for a deeper understanding of the story?

3. Wiebe-Neufeld’s story has a refugee theme. How was the baby Jesus like a refugee? Does our modern celebration of Christmas make enough room for refugees and their stories?

4. Has your family considered doing a Christmas project like that of the Gingrich family? What are the challenges in organizing this type of alternative to exchanging gifts? What are the benefits?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.