As the notorious persecutor Saul of Tarsus was transformed by God’s grace and is now remembered as the “apostle to the gentiles,” so Bogale Kebede, charged and imprisoned for murder, was transformed by God’s grace to become Christ’s apostle to the Kaffa.

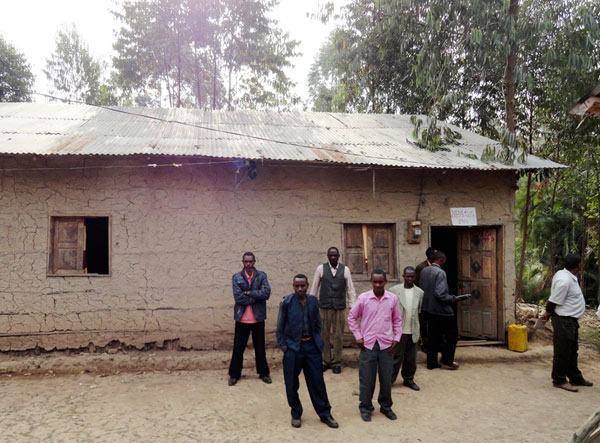

More than any other person, Kebede was the founder of the Meserete Kristos Church (MKC) in remote western Ethiopia’s Kaffa Region, and remains the primary leader and driving force that guides its development. Currently living in Bonga with his wife, Fantaye Mukuria, and their four children, he serves as general secretary for the national Mennonite church’s regional office.

A voice from the Lord

Kebede was born in Bitta Wereda in Kaffa Region. In 1985, he was accused of murder and put in prison in Jimma. An older prisoner, Ato Tesfaye, who was an evangelical Christian, tried to witness to him, but was rebuffed. After two years, the judge sentenced Kebede to 20 years.

The harshness of his sentence made him open to accept Christ now. Tesfaye encouraged him, saying, “This [sentence] is man’s decision, but not God’s decision.” While he was bowing down and Tesfaye was leading him in the sinner’s prayer of repentance, Kebede heard a voice saying, “You must ask for your case to be reviewed.”

He thought it must be the voice of the old man, so he asked Tesfaye, “Are you speaking to me about appealing?” The old man answered, “No, I asked you to repent!” The voice and the message came again. Kebede decided it must be from the Lord, so the next morning he wrote his appeal letter. Tesfaye laid his hands on the letter and prayed.

Kebede began to witness to the other prisoners. God reinforced the truth of his witness by doing miracles through him. In the time he remained there, 65 prisoners were converted. With help from the Jimma Meserete Kristos congregation, a church was opened in the prison, where he also learned the trade of carpentry.

The judges did their investigation, and after 16 months they found no evidence. As a result, Kebede was unconditionally released on Dec. 13, 1988.

Witnessing results in conversions

He went home to Kewa Gerba in Kaffa Region, where he witnessed to his mother and brothers. His mother was the first to become a believer; his younger brother, Baheru Kebede, followed.

Kebede took his brother back to Jimma for spiritual teaching and baptism. Kebede got a job in the building trade in Jimma, where he later opened his own carpentry shop while continuing to witness for Christ. Like the biblical apostle, he rented a room, worked all day and held prayer meetings in his room at night.

He would go to his home in Kewa Gerba every two months to witness there, and then return to Jimma for two months of labour at his trade to support himself. There were no other evangelicals in Kaffa at that time, but after the first two months there were four believers.

A felt call to full-time ministry

By the end of 1993, Kebede felt called to become a full-time minister of the gospel. He volunteered for the One-Year-For-Christ program and went for the required six weeks of training in Addis Ababa at the newly formed Meserete Kristos Church (MKC) Bible Institute. He was assigned to Kewa Gerba as a full-time evangelist, where he served for nine years.

In 1994, MKC leaders in Jimma and Addis Ababa asked the church to rally in a “Kaffa for Christ” movement to pray for and support Kebede as he entered into a full-time ministry of planting the church in Kaffa Region. MKC wrote letters to all the congregations and to some of the former Mennonite missionaries requesting their prayer and financial support.

Support was forthcoming, and Bogale’s work came under the supervision and support of the MKC Evangelism and Missions Department.

‘Power encounters’

This remarkable people’s movement can be explained, like scenes from the Book of Acts, as a “power encounter” between the Holy Spirit and Satan. It is what happens when God’s Spirit-filled apostles come preaching a gospel of Jesus Christ with conviction and power; a gospel of power that heals the sick and casts out demons; a liberating gospel that frees people from the curses that have held them captive in the bondage of fear, ignorance, superstition, and the oppression of evil spiritual forces exercised by the shamans or “witch doctors” who inflict great suffering upon the people financially, physically, spiritually and mentally.

Kebede had a vision of a great tree. The Lord told him to break off a small branch and plant it in the ground. He said the big tree was the dominion of witchcraft in Kaffa. The branch would grow into a new tree of righteousness. The old tree would be torn out by the roots—and so it was. As he witnessed for Christ, he was given the power of the Holy Spirit to heal the sick and cast out demons. People turned to Christ by the thousands, so that by 2002 there were 8,000 believers scattered in eight congregations and 35 church-planting centres.

As Kebede preached the gospel, healed many sick and cast out demons, people were set free and their lives were changed, so much so that the witch doctors found themselves to be helpless against his power over their dominion. Masses of people forsook the witch doctors and turned to Christ for their salvation and security.

The occult powers that controlled the region were centred in seven powerful witch doctors. Five of these, when they saw the power of the gospel and their people being transformed, also accepted Christ and were baptized.

‘What will happen, I will accept’

The one called Gerebecho, who ruled all the other witch doctors, saw the people and the witch doctors one by one forsake the occult and surrender to the Jesus that Kebede and his younger brother preached. He lost confidence and hope in himself. When Kebede came to the area where he was, Gerebecho fled to another area. When Kebede came there, the witch doctor again fled to another place. Finally, he told his relatives and family, “I cannot flee anymore. I will wait for him. Let him come and face me. What will happen, I will accept.”

His relatives invited Kebede to come, and Gerebecho removed all of his medicines, witchcraft paraphernalia and furniture from his house in preparation. When Kebede came, Gerebecho laid down on a mat on the floor; he was afraid after hearing stories of how the other witch doctors had fallen to the ground and screamed in pain as Kebede rebuked and drove out the demons.

People gathered in the house and Bogale preached to them and healed some sick. Gerebecho gave himself to Christ and gave land to the church for a building. He stayed as a strong Christian for about eight months, but got sick and Bogale took him to the hospital in Jimma, where he died. He became the first person to die and be buried as a Christian in that area.

With the conversion of these witch doctors, people were free and there was a mass movement into the church. Today, in the woredas (districts) of Bitta, Chena and Gesha the hold of witchcraft is completely broken and has disappeared.

More than an evangelist

Kebede’s ministry was not only about evangelism. He had a holistic concern for the backwardness and poverty of his people. They were simple subsistence farmers who knew nothing of improved agriculture. He gathered advice from church leaders and government agricultural research centres, and encouraged his people to try improved methods.

In 2002, new believers of the Shota congregation decided they would no longer pay taxes, resulting in the government tax collectors becoming concerned. They approached Kebede, asking if he could do something to change his followers’ minds before they took drastic action, like confiscating the people’s property.

He called the believers together and asked them why they refused to pay the taxes. They replied that, since they learned they were free from the law in Christ, they were no longer under obligation to pay. Kebede gave them further instruction from the Bible, saying they were to respect and obey the government officials and pay their taxes. The people all went home, gathered their money and came to pay their taxes. The government officials were amazed at Kebede’s influence, and they became very cooperative, offering to give any land he needed for church programs.

Kebede was deeply involved in the development of the Kewa Gerba community. At the time of his conversion and the beginning of his ministry there, people lived much as they had for centuries in the past. Kebede and church leaders encouraged the community and the local government officials to build roads and elementary schools.

A believer had started a private clinic, but had trouble running it, so it was taken over by the MKC Relief and Development Association. The association also built a new elementary school and a dry-season gravel road from Bonga to Kewa Gerba.

Evangelist becomes bridge builder

In 2002, the Muslim family of the person Kebede had been charged with murdering won the cooperation of local officials and police, who arrested him on the original charge of murder from which he had been acquitted back in 1988. Since he had lost his acquittal document, he was imprisoned again, this time in Bonga. There, he used his skills as a builder to construct a chapel in the prison and seized the opportunity to evangelize many prisoners, a number of whom turned into productive citizens upon their release. After two-and-a-half years, an MKC lawyer was able to prove that Kebede’s case had been settled long ago, and he was released a second time.

It was in the Bonga prison that Kebede was able to first evangelize the Menja, a despised and oppressed people. Upon his release, he went with his wife and lived among them. He ate what they ate, slept where they slept, healed their sick, delivered them from evil spirits and won them to Jesus. But the Kaffa people back home were so disgusted with the couple for associating with these outcast people that they shunned them for a time.

The Menja keep cattle, live in very simple houses, cultivate ensete (a type of banana) and a few simple food crops, and harvest wild honey. Traditionally, the Menja were considered “unclean” by the dominant Kaffa because they do not wash their bodies and they eat dead animals. They were seen by the Kaffa as “wild animals” and “sub-human.” There was no fellowship, no shaking hands, no eating together, no entering the same house and no intermarriage between them. The Menja people themselves accepted that they were different and declared themselves as “untouchables.”

The MKC of Kaffa Region welcomed the Menja converts into their churches, but assigned them separate rows of seats. The Kaffa thought they would die if they touched the Menjas until one day Bogale started washing the Menjas’ feet during communion and nothing happened to him. This was a great challenge for the church.

Today, Menja children are going to school, even university. And the church teaches that there should be no discrimination. However, at the grassroots level Kaffa Christians have a hard time mingling with their Menja brothers and sisters. Despite Kebede’s influence and example, there is still a tendency to form separate congregations and Menja churches have their own evangelists.

There are currently about four local churches and 25 church-planting centres among the Menja, with about 6,000 members.

Challenges for a growing church

In 2004, the MKC separated Kaffa from the Jimma Region and made it an independent region with its office at Bonga, and appointed Kebede to move there to assume the role of regional office coordinator, a role he holds to this day.

Sixteen years ago, believers in Kaffa numbered only 300. Now, the Kaffa regional office oversees 21 local churches and 71 church-planting centres that serve more than 19,000 believers. Besides these, there are now seven other evangelical churches in the 10 woredas of Kaffa. About 40 percent of the believers in the region are MKC members.

This emerging church faces many challenges:

- The gospel is proclaimed in the vernacular Kaffa language, but there is no translation of the Bible yet.

- Witchcraft is stamped out in the areas where the churches are present, but how should they indigenize the gospel into the local culture?

- In worship, the dominant practices of the MKC are being adapted, especially in the hymnody and style of praying, but how much change should be expected at the cultural level?

- Which cultural practices should be abolished? Which modified? Which maintained? Which embellished with added Christian value?

- Lines can be drawn on practices such as smoking, drinking, murder and adultery, but how can problems related to polygamous marriages, for example, be solved?

- How can the church deal with the deep tribal discrimination that separates the Menja and the Kaffa ethnic groups?

- In an economy of extreme poverty, how do leaders grow the church and expand the ministry into new areas? How does the church pay the salaries of evangelists and administrators, and build more churches?

With a low level of education and skills among its leaders, how and what does the church teach the people, and how does it train new leaders so they can teach better and grow the church? So far, only three people from Kaffa MKC congregations have been able to study at Meserete Kristos College. But with membership growing at about 3,000 per year, how can Kaffa leaders be trained to meet the need?

These are some of the challenges that keep the apostolic Bogale Kebede from resting on his much-deserved laurels, and which should set the wider church thinking about ways it can help.

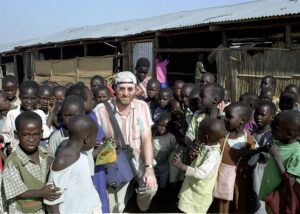

Carl E. Hansen of Harrisonburg, Va., is director of advancement at Meserete Kristos College, Ethiopia.

For discussion

1. How do you explain the voice that Bogale Kebede heard while he was in prison? Do you know of others who have heard such a voice? How was Kebede convinced that this voice was from God? How important is it to have such a message confirmed?

2. In the 1990s, the Meserete Kristos Church in Ethiopia grew exponentially. What are some similarities between its growth and what happened in the Book of Acts? What questions do you have about witchcraft and about Kebede’s healing ministry?

3. When Europe was Christianized many hundreds of years ago, the holidays of Christmas and Easter were incorporated into traditional celebrations and came to include pagan symbols such as the Christmas tree and the Easter bunny. Has this been a successful integration of indigenous culture and Christianity? What advice do you have about how to indigenize the gospel into local culture?

4. Carl E. Hansen describes tribal discrimination between the Menja and Kaffa ethnic groups in Ethiopia. Do we have any similar discriminatory attitudes? Whether in Canada or in Ethiopia, how should the church discourage our culture’s unchristian values and attitudes? How do we identify which values and attitudes are unchristian?

–By Barb Draper

See more about Ethiopia:

Ethiopian Church grows in maturity

They can't keep up

CIDA minister praises MEDA project

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.