These are times of uncertainty and hatred, when our political and social discourses are marred by xenophobic, Islamophobic, and just plain racist rhetoric. (Remember the niqab debate during our Canadian election? the calls to turn Syrian refugees away simply if they’re Muslim? the sinister tone of Donald Trump’s anti-Muslim comments in the U.S.?) In light of all of this tension between so-called “Christianity” and Islam, I call for a turn to Mary.

Now before you go accusing me of some escapist, apolitical form of faith that has more in common with shopping your cares away than any kind of good news for the oppressed, let me explain.

You see, Mary, Miriam (Hebrew), or Maryam (Arabic) of Nazareth, the mother of Jesus (or Issa, in Arabic), actually represents common ground between all three Abrahamic faiths, as a Jewish woman who is the most important female figure in both Christianity and Islam.

It’s true. Islam has its own interpretation of Mary as one of God’s chosen people and the mother of Jesus, who is one of the major prophets of Islam. Just as Mary speaks the longest passage attributed to a woman in the New Testament–the Magnificat–so in the Qur’an, the sacred scriptures of Islam, Maryam is the only woman to have an entire sura or chapter dedicated to her, namely, Sura 19. Part of her story also appears in Sura 3, and she is mentioned in passing in Sura 4, Sura 21, and Sura 66. Counter-intuitively, this means that she’s mentioned more times in the Qur’an than in the Christian Bible![1]

Like the Gospel of Luke, Sura 19 of the Quran recounts the foretelling of the birth of John the Baptist to Zechariah, followed by the Annunciation to Maryam. It affirms the virginal conception of Jesus in more precise terms than in Luke as well. But, contrary to the Catholic beliefs about the perpetual virginity of Mary (the idea that Mary was a virgin before, during, and after giving birth, and that she gave birth painlessly), the Qur’an mentions that Maryam experienced such great “pains of labour” that she cried out, “Oh, if only I had died before this and passed into oblivion!” (Sura 19:23).

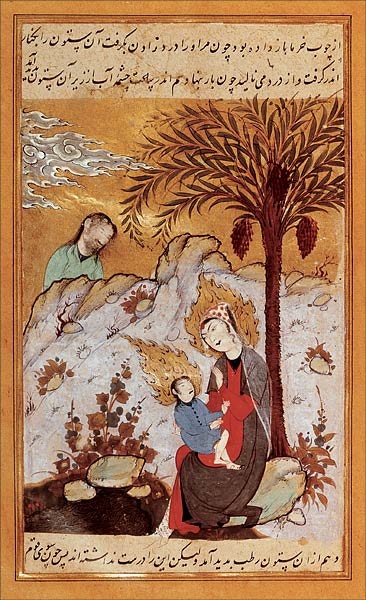

Though she was alone during her labour (i.e., without Joseph),[2] God cared for her. An angel told her, “Do not despair. Your Lord has provided a brook that runs at your feet, and if you shake the trunk of this palm tree, it will drop fresh ripe dates on you. Eat and drink and rejoice” (Sura 19:24-26). In this way, Maryam was sustained by God through the pain of childbirth.

Not only does this account provide fascinating details to round out Luke’s all-too-short “the time came for her to deliver her child. And she gave birth to her firstborn son” (Luke 2:6-7, NRSV), but it also leaves us with the striking image of God as a midwife, a profound but neglected image which in fact resonates with other passages in the Hebrew and Christian scriptures. Psalm 22:9-10, for instance, states, “Yet you are the one who took me from the womb. You kept me safe upon my mother’s breasts. I was cast upon you from the womb.”[3]

After Jesus was born, the Qur’an states that Maryam presented her baby to her community, and they accused her of being “unchaste.” But the infant Jesus spoke up in defense of his mother—not refuting the accusations outright, but asserting that God blessed him, made him a prophet and, interestingly, also made him “dutiful toward my mother” (Sura 19:32).

According to Catholic feminist theologian Elizabeth A. Johnson, Mary also has a place in the spirituality of many Muslims, making this a major point of similarity between Catholic/Eastern Orthodox Christians and Muslims.[4] For example, in Egypt, the place where Mary and Joseph fled to escape Herod’s massacre of baby boys (Matthew 2), there are some Muslims who visit Coptic Christian churches to pray to Maryam there as well as in their home mosques. She is seen, as a young woman named Youra put it, as being “able to face a lot of hardships in her life because of her faith, her belief in God.”

Apparently, some Muslim women who want to get pregnant go to St. Mary’s Coptic Church in Cairo to petition Maryam. This means that in some churches, Muslims and Christians stand side by side lighting candles to this powerful woman who inspires and empowers people of both faiths.[5]

As we continue our way through Advent as Christians, here is yet another reason to turn our attention toward Mary/Maryam, whose life and example, after all of these generations, still has the power to bless: she continues to draw connections, spark conversations, renew relationships, and even, dare I say it, to point us toward the very real possibility of peace.

_______

[1] See Elizabeth A. Johnson, Truly our Sister: A Theology of Mary in the Communion of Saints (New York: Continuum, 2003), 4, 263, and Maureen Orth, “Mary: The World’s Most Powerful Woman,” National Geographic 228, no. 6 (Dec. 2015): 36. Available online: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2015/12/virgin-mary-text

[2] Orth, 54.

[3] See also Psalm 71:6. Translation: Doris Jean Dyke, Crucified Woman (Toronto: United Church Publishing House, 1991), 61.

[4] Johnson, Truly our Sister, 4-5. Catholics differentiate between the “veneration” of Mary and the saints and the worship of God and Jesus Christ.

[5] Orth, 54-59.