Mark Olfert has always been passionate about helping people. He wishes the systems in Canada would do more to support people, too.

Olfert, 60, is an anti-poverty activist and a member of Hope Mennonite Church in Winnipeg, Man. He advocates for a guaranteed liveable income, something he says would have made a big difference numerous times in his own life.

For many years, Olfert rented stable housing and worked a steady job at Superstore. Several years ago, however, he had to take a leave from his job because of an injury and subsequent surgery on both knees. When he returned, he had a boss whose mean treatment of Olfert caused him so much stress that work became a harrowing experience. “I just couldn’t work under those kinds of conditions. I had to stop,” he says.

The year after he stopped working, 2018, was a real struggle. Friends helped him with rent while he struggled to navigate the bureaucratic systems for various benefit plans. Employment and Income Assistance was not enough for him to live on. Then his landlord renovated his apartment and dramatically increased the rent. Olfert could no longer afford it.

Manitoba has a shortage of social housing, with many units labelled affordable but still priced far too high for people surviving on income assistance. Olfert found a unit he could afford in a rooming house, but it was in bad shape, including a leaking ceiling and a soon-broken furnace. He says he was one of the lucky ones, with his own bathroom and kitchen. Others had to share a bathroom, and the conditions were unspeakable.

He had lived there for two years when a fire ravaged the building. Olfert was rushed to the hospital, where he was checked and cleared, but he lost almost everything he owned.

He moved to a better apartment downtown, but it was loud. “I was just terrified all the time, hearing all these sirens . . . it scared me,” he says. “I was traumatized because of the fire.”

In August, within six months of the first fire, he was evacuated from his new home for two weeks when a neighbouring building went up in flames.

Throughout all this, Hope Mennonite showed up for him with money, meals, supplies and friendship. “Hope has shown me how much they care about others,” he says. “They showed so many acts of kindness to me that I will never forget.”

He started attending the church in 2019 and became a member later that year. “It made me so happy to know that I belong to a faith community that really cares about me . . . It makes me very emotional thinking about it. It feels good to be loved.”

The care he has received from his congregation and others in his community inspires him to help others. “I’ve had lots of people help me out over the years. It’s my way of giving back.” Volunteering is also a culture he was raised in, as his parents volunteered at the Mennonite Central Committee thrift shop and his mom knitted endless items of warm clothing for the Christmas Cheer Board. “It’s part of our family,” he says with a smile. “That’s just the way I’m wired.”

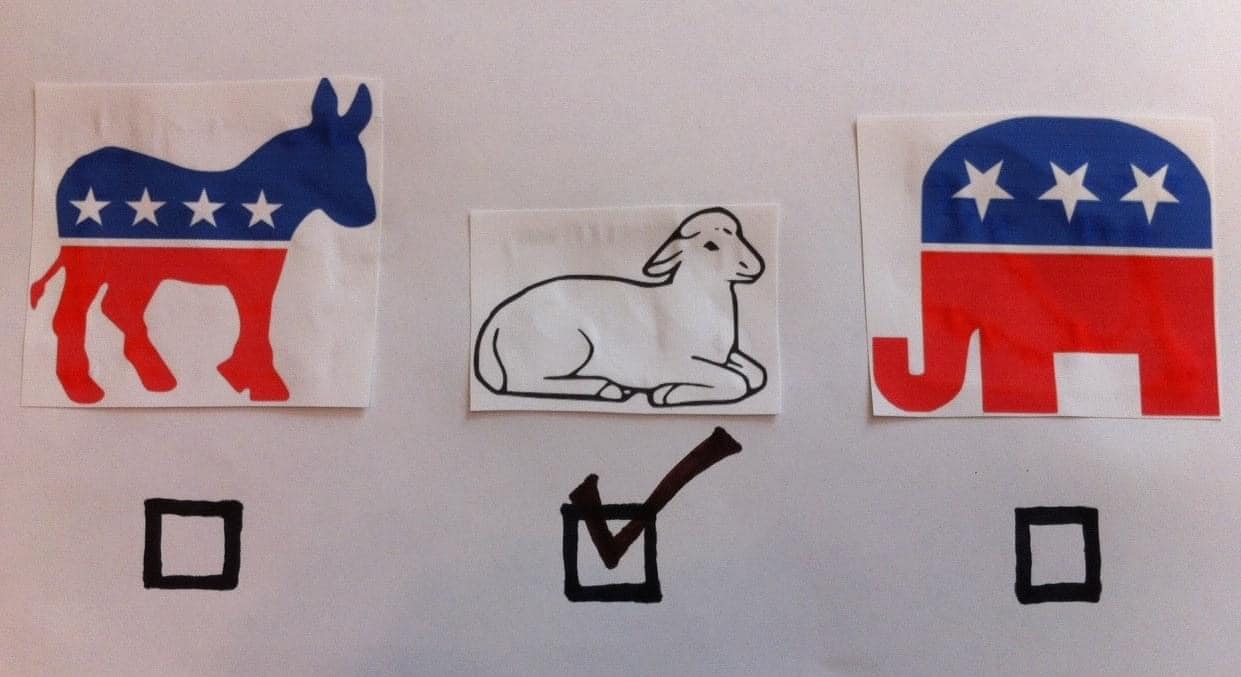

Olfert volunteers weekly at 1JustCity, a non-profit helping people experiencing homelessness, food insecurity and marginalization. He runs bingo by phone for seniors who are frequently housebound, joins protests with multifaith climate action groups, and campaigns for members of Parliament. It was after meeting Leah Gazan, Member of Parliament for Winnipeg Centre, that he got interested in guaranteed liveable income, or basic income, as a model for addressing poverty.

Evelyn Forget, a health economist and professor at the University of Manitoba, defines basic income as “a transfer of money from the government to individuals, sufficient for them to meet their needs . . . to participate in a reasonable way within the community. It’s available both to people who don’t work and who may currently be subsisting on something like employment and income assistance . . . but it’s also available to people who are working but who don’t earn enough to raise themselves and their family above the poverty line.”

She’s heard all the misconceptions and assumptions about a basic income program, but she repeatedly points to the research and studies that show it works. The common objection is that if you give people money they will stop working. “There’s no evidence of that,” she says. “There are projects around the world . . . people have done this over and over and over again, and there’s never any significant reduction in the amount of work effort.”

Another main criticism is that it’s too expensive. “People forget that poverty has a lot of costs associated with it,” says Forget. Taxpayers spend more on healthcare, prisons, education and welfare when poverty increases. She references a study done in Ontario a few years ago, which calculated that expenditure related to poverty costs 6.6 percent of the GDP annually. In Manitoba, that’s $4 billion. “We’re paying a lot of money . . . to treat poverty in a really inefficient, ineffective and undignified way,” Forget says.

So, it’s not about spending a lot of money, but about how we choose to spend it.

“I believe as a Christian ethic we all deserve to have a guaranteed basic income,” Olfert says, “because a lot of people are struggling out there. I’ve been one of them, and it does make a difference when you get people helping you out. I really want people to get help. As a Christian I feel my duty is to help people.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.