Land acknowledgments are usually spoken, but Angela Hildebrand was curious how they could be expressed in other mediums. “Being a very visual person, I resonate a lot with things I can see, touch,” she said. “So I began to think about, what would that look like for me, for our fellowship?”

Hildebrand is a member of Fort Garry Mennonite Fellowship (FGMF) in Winnipeg and calls herself a “closet quilter.” She’s been creating quilts and fabric art since the early 2000s, but she hasn’t shown her creations to many people. That changed, however, during the pandemic, when she was inspired to quilt a land acknowledgment banner for her congregation.

Her daughter, who teaches at a school in Winnipeg’s inner-city and works with an Indigenous elder, encouraged Hildebrand to connect with an elder to ask for permission and guidance on her project.

But Hildebrand didn’t have a personal connection with any Indigenous elders. “My first aha moment came with realizing how small my relationship circle really was,” she said. She reached out to Dorothy Fontaine of Mennonite Church Manitoba, who connected her with Melvin Swan, an elder of Fontaine’s late husband, Vince.

Swan passed on his blessing and affirmation, offering two suggestions: to incorporate actual words into her piece, which was initially only imagery, and to collaborate with an Indigenous artist.

Hildebrand again faced her limited network, but reached beyond it with a simple online search. Through this, she connected with Melanie Gamache, a Francophone Métis beadwork artist located in Sainte-Geneviève, Manitoba. Two weeks later, they met at a small rural restaurant and began collaborating on the project.

Gamache owns and operates Borealis Beading, a venture she started to create and sell beadwork art. It has grown to include hands-on experiences that have included beading workshops, nature walks, sharing food and conversation—both on her property and in a travelling workshop.

For Hildebrand, collaborating was another new challenge, since she usually quilts independently. She had to practice patience, as the process took longer than she expected. She had to open herself to approaching things differently. “I’m actually grateful for the time it gave me to reflect and build relationships with the people involved,” she says.

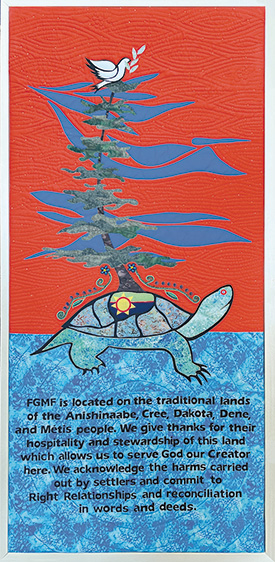

When Gamache agreed to join the project, Hildebrand gave her some fabric and an image reference, then left her complete creative freedom to contribute as she wished. Gamache had never done anything like it before. She created two pieces of beadwork, containing five-petal flowers, fiddleheads and berries, which tell the story of the Métis people. Gamache explained that the Métis came to be known as the flower beadwork people, expertly embellishing all their clothing and bags, especially with five-petal flowers.

The seven berries on each motif represent the Seven Sacred Teachings of love, respect, courage, honesty, wisdom, humility and truth. Gamache said she would like to see more people following these teachings, not just in the church but everywhere. “These seven teachings are just life skills . . . you don’t have to be Indigenous to believe in them,” she said.

The intertwining plants also represent new growth. “The partnership they’re working on in doing this quilt is growth,” Gamache said, of FGMF. “They’re growing in how they’re opening up to acknowledge what’s been happening . . . churches and Indigenous people, there’s always conflict there, so to have that recognition in a church is growth.”

Hildebrand’s part of the banner begins in the centre with Turtle Island, an Indigenous name for North America and a reference to the widely held Indigenous creation story. The tree on Turtle Island “symbolizes the longstanding presence of Indigenous people on this land.” Also depicted are the Treaty 1 flag, an orange sky of sunsets and sunrises for those who died or survived in the Indian Residential School system, and a dove, symbolizing Mennonite settlers arriving to the land.

Hildebrand’s part of the banner begins in the centre with Turtle Island, an Indigenous name for North America and a reference to the widely held Indigenous creation story. The tree on Turtle Island “symbolizes the longstanding presence of Indigenous people on this land.” Also depicted are the Treaty 1 flag, an orange sky of sunsets and sunrises for those who died or survived in the Indian Residential School system, and a dove, symbolizing Mennonite settlers arriving to the land.

“We offer our olive branch to the Indigenous community, acknowledging and asking for forgiveness of our past wrongs and our commitment to peace and reconciliation,” she said.

This is only some of the meaning Hildebrand has woven into the many components of the banner. There’s a small sign beside where it hangs in the church foyer that explains the different elements, but she also wanted to leave the quilt open to be interpreted differently by each person.

“Land acknowledgment and truth and reconciliation is as much an individual responsibility as it is a corporate or community responsibility,” she said.

At FGMF, land acknowledgments aren’t spoken in the same way every worship service, Hildebrand said. Rather, each worship leader does it in a way that encourages personal reflection and is meaningful to them.

For the banner’s text, she worked together with her congregation’s worship committee to try to convey the full idea well in only a few words. She shared the quilt with the congregation in a worship service and received much appreciation for her contribution. “It was very meaningful for me,” she said.

The project now complete, Hildebrand is left with the lasting impact of the people she met along the way. “It’s only two small connections, but it’s helped really broaden my understanding and responsibility to expand my circle of friendships and relationships.”

Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Manitoba? Send it to Nicolien Klassen-Wiebe at mb@canadianmennonite.org.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.