October 22 was a normal Sunday. I had just arrived at Rockway Mennonite Church in Kitchener, Ont., when Conrad Brunk approached me. He is a fellow Rockway member, a former colleague at Conrad Grebel University College and a former next-door neighbour in Harrisonburg, Va. when we were very young. He wanted to talk about “the piano issue.”

My heart froze. Had I played too loudly? Or did he want me to play the hymns “just as written,” as a former theology professor had once suggested?

I was unprepared for what he said: “We Brunks want to apologize to you and your family for the piano ban our father and grandfather enacted within the Virginia Mennonite Conference in the last century.” I immediately burst into tears.

Conrad Brunk’s father and grandfather—George R. Brunk II and George R. Brunk I—were leading figures behind a move of the Virginia Mennonite Conference that forbade ordained ministers or faculty of Eastern Mennonite College (now University) from having musical instruments in their homes. Mennonites did not have instruments in churches at the time.

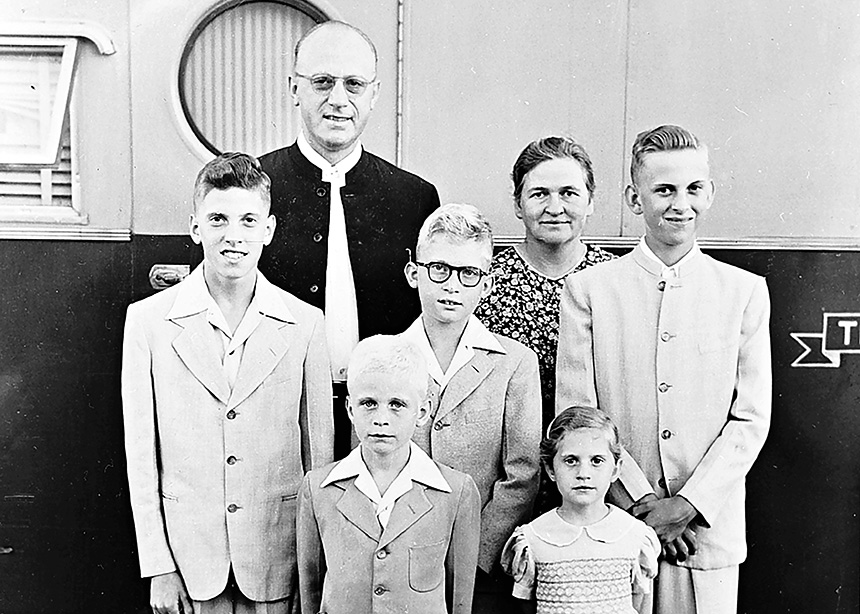

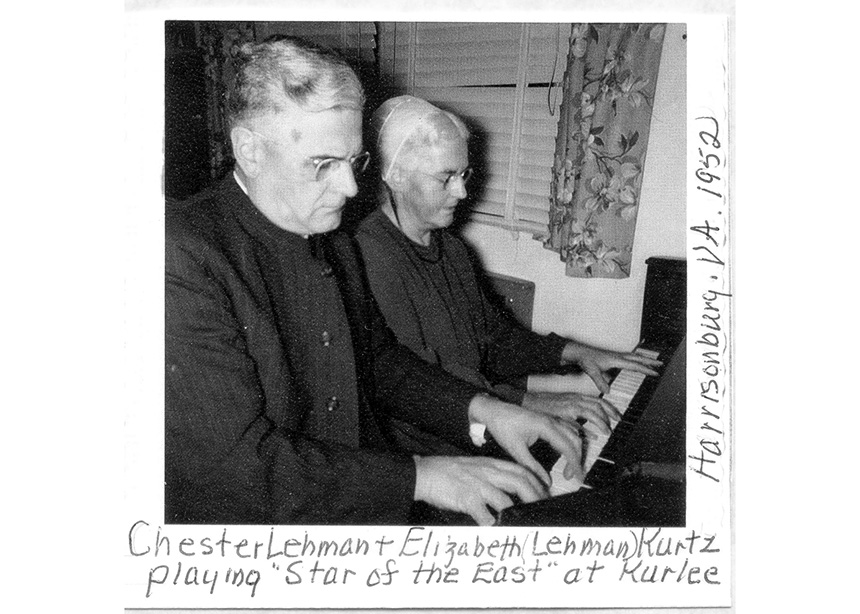

The ban was in effect from 1927 until 1947. It devastated my mother’s family. My maternal grandfather, Chester K. Lehman, was an ordained minister, faculty member of Eastern Mennonite College (EMC) and a great lover of music, having grown up in an exceptionally musical family.

Since my grandfather was both an ordained minister and an EMC faculty member, my grandparents had to remove the piano from the family home.

The piano was a vital part of family life. My mother had been learning to play at the time. For her younger sister—my aunt—those inordinately sad days created her earliest memory.

Many others throughout the Virginia conference were similarly affected, as pianos, organs and other musical instruments were taken out of homes. As noted in the Brunk family apology, J.B. Smith, the first president of EMC, abruptly resigned in 1922 rather than get rid of the piano that he and his wife had just purchased. While the formal ban was not yet in place at the time, the pressure to get rid of instruments went back to at least 1908, when my great aunt, Annie Wenger, was forced to give up her organ.

Apology

A century later, I’m in tears in the sanctuary of Rockway Mennonite Church, learning that the Brunk family remembers and cares about the event that caused my mother’s family, and so many other families, tremendous grief.

Several weeks later, I received an official letter of apology from Conrad Brunk and his siblings, Gerald R. Brunk, George R. Brunk III, Paul W. Brunk and Barbara Brunk Gascho. The apology was addressed to me and my sisters, Kathleen Weaver Kurtz and Dorothy Jean Weaver; to our Aunt Dorothy Lehman Yoder, the only living child of Chester K. and Myra K. Lehman; and more generally to the “family of Chester K. Lehman and to all persons similarly affected by the banning of musical instruments in Virginia Mennonite Conference.”

The Brunks offered their “sincere apology for the actions of [their] forefathers in this sad history,” and expressed “deepest sorrow and regret” for the harm caused by the ban.

The Brunks acknowledged that the ban was implemented largely due to the personal views and strong influence of their grandfather, George R. Brunk I, and, for much of this life, their father, George R. Brunk II, who was famous for his tent revival meetings across North America. He died in 2002.

These present-day Brunks wish for their letter of apology to be a public expression of their sentiments. Furthermore, they felt it was imperative for them to take responsibility for the actions of their father and grandfather.

“In recognition of this history and of the serious harm that was, and continues to be felt,” reads the letter, “we, the grandchildren and children of these two church figures, wish to express to you, and all affected, our deepest sorrow and regret for this harm. And in recognition of the fact that it is often later generations upon whom the responsibility falls for ‘the sins of the fathers,’ we offer to you, and to all, our sincere apology for the actions of our forefathers in this sad history.”

The dear piano

My mother, Miriam L. Weaver, touchingly recounted her story of the loss of the family piano as part of a music drama I wrote. “Quietly Landed?” included the stories of numerous women who had been silenced. My mom was involved in performing it in the United States and Canada shortly before her untimely death in 1997.

In the drama, she says: “I remember the tremendous sadness I felt as our piano was sitting on the back of the truck that was to take it away, and a man from the store was standing at the keyboard and playing something, and I looked longingly at our dear piano as the truck moved down the driveway and out into the street. Now we would no longer hear my father play Ben Hur’s ‘Chariot Race,’ ‘Star of the East,’ and other favourites of ours. And worse yet, how would I ever learn to play?”

Poet Julia Kasdorf, also in this drama, maintains that each time my mother read her story, the driveway grew longer and longer. The pain was palpable.

By the time I grew up, pianos were back in homes, but not yet in any of the Mennonite churches in the eastern U.S. or parts of Ontario, where it was all pitch pipes and a cappella singing. One can take a trek to a local Old Order or conservative Mennonite church in Waterloo County, Ont., which I did recently, to hear the kind of singing I grew up with.

Among Amish and certain Old Order and Old Colony Mennonites, four-part singing has been, and sometimes still is, considered worldly, especially by groups who migrated to Latin America.

Lifting the ban

The ban was officially lifted in 1947. Although the effects lingered, George Brunk II eventually had a complete change of heart.

In the 1950s, when he had his tent meetings in Canada, he realized many Ukrainian Mennonites (sometimes called Russian Mennonites) had pianos or organs in their churches. Soon he, too, would allow pianos to accompany singing in his tent meetings. As noted in the apology, he even bought an organ for his wife and taught himself to play!

“We have reason to believe,” the Brunk family writes, “that, were our father alive today, he would join us in this apology.”

The fact that the Brunk family chose to take the initiative to account for the actions of their forefathers sets a new tone. Their actions serve as a model for how to deal redemptively with troubling issues from the past.

As I embrace my a cappella heritage with increasing enthusiasm and remain exceedingly happy we always had a piano in our home, I thank the Brunks for their apology and the chance to revisit our past with grace, gratitude and forgiveness.

Carol Ann Weaver is a composer, pianist and professor emerita of music at Conrad Grebel University College.

Music and worship practices

The use of instrumental music remains an issue with some Mennonite groups. The most traditional sing in unison in German for worship, but many sing four-part harmony in English at other times. There is a broad range of acceptance of musical instruments in homes among conservative Mennonites.

Mennonite groups in Canada that do not use musical instruments in worship include:

- Amish

- Beachy Amish

- Conservative Mennonite Church of Ontario

- Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (Holdeman)

- Markham-Waterloo Mennonite Conference

- Midwest Fellowship

- Nationwide Fellowship

- Old Colony Mennonite

- Old Order Mennonite

- Sommerfeld Mennonite

—Compiled by Barb Draper

History of discord in Ontario churches

In the middle of a fierce conflict in the Mennonite church 140 years ago, the Kolb family defied church rules and installed an organ in their home. What made this particularly galling to the traditionalists was that Jacob Z. Kolb was a deacon at what is now First Mennonite Church in Kitchener, Ont. The Swiss-descended Mennonites of Waterloo Region had a long history of eschewing musical instruments.

Likely in response to this infraction, church leaders passed a resolution in 1886 saying: “Instruments have no room in the Gospel. We are agreed to testify against them, and to exercise our influence to foster awareness that the church members put them away.”

According to E. Reginald Good’s history of First Mennonite Church, the organ in the Kolb home remained because it was the property of one of the deacon’s sons, who was not yet a member of the church.

Within a few years, the church divided. One group was soon learning to sing in four parts and members were able to have musical instruments in their homes. Two of the Kolb sons played key roles in advancing vocal music in the Mennonite church.

It took decades for most Swiss Mennonite congregations to adopt musical instruments for worship. Even today, Elmira Mennonite still mostly sings a cappella.

At Floradale Mennonite, first a piano was donated for use with children in the basement. Eventually the piano made its way up to the sanctuary, but it was the 1980s before it was regularly used to accompany congregational singing.

—By Barb Draper, Editorial Assistant

For discussion

1. What role has music played in your family life? How much has the availability of recorded music changed the role of making music? Do we sing less than earlier generations?

2. What might have been the rationale for Mennonite church leaders of generations ago to declare that musical instruments were inappropriate? Why do some Mennonites still not use instruments in worship?

3. Why do you think the Brunk family decided to issue an apology in 2022? How effective is this type of apology?

4. Carol Ann Weaver says she embraces her “a cappella heritage with increasing enthusiasm.” What value do you place on the Mennonite church’s heritage of four-part, unaccompanied singing?

5. What do you think is the future of church music?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.