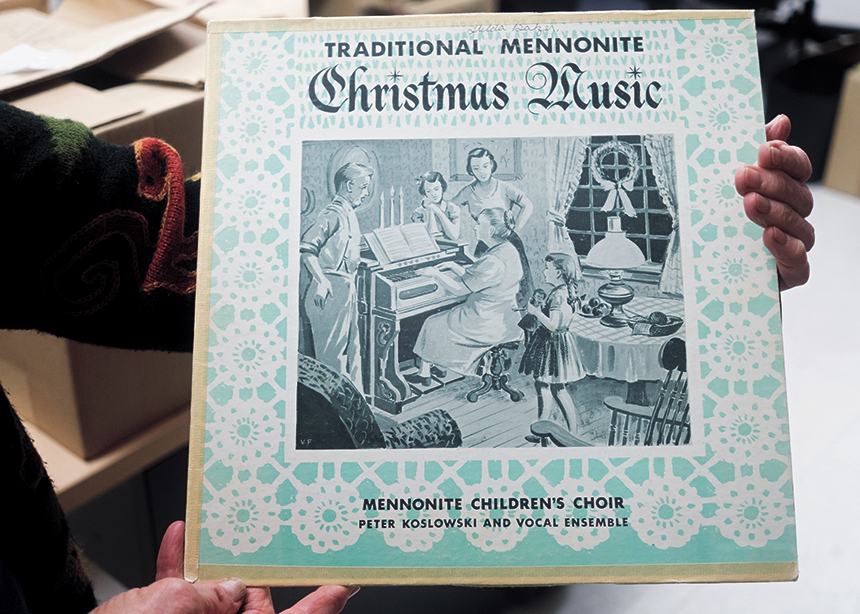

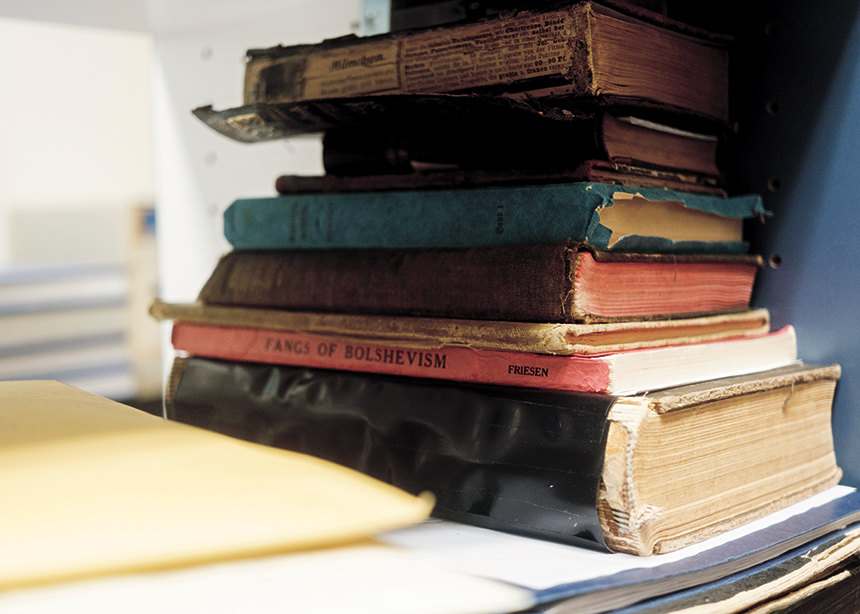

Through an easily overlooked side door and down two flights of stairs at Bethany Manor Senior Living Complex in Saskatoon one will find the archival rooms of the Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan (MHSS). The cozy basement space holds thousands of Mennonite historical materials including Bibles, maps, newspapers, school yearbooks, Mennonite song books, vinyl records and even a collection of client files from a law office.

Working among the towers of boxes and narrow shelves are some of the faithful volunteers—Victor Wiebe, Lorene Nickel, Kathy Boldt, Hilda Voth and Elva Braun.

“We have about 12 different people who regularly volunteer here in the archival room,” explained Wiebe, “and there’s probably another 20 or so volunteers who help out with MHSS special events [as well as] the volunteer board members.” The society has no paid staff. It’s funding comes from memberships, donations, grants and book sales.

In the early 1970s, as Frank H. Epp was doing research for his landmark book Mennonites in Canada, he reached out to people across Canada who were knowledgeable about Mennonite history. Epp’s project prompted historical enthusiasts in Alberta and Saskatchewan to form a Mennonite Historical Society together in 1975. In 1993, the society separated, creating one for Saskatchewan and another for Alberta. “The Alberta folks just got tired of driving out to Saskatchewan,” joked Wiebe.

In the basement archival room, donations are collected and donors are issued a Deed of Gift. This record ensures a listing of what was donated and legally transfers the materials. Volunteers then spend days (often months) sifting through material, keeping what is relevant, setting aside duplicates, and cataloguing all the items in both a digital and print file. Finally, the materials are filed and shelved in the correct section, according to the Canadian Archival Standards.

Having an extensive historical archive is common in many Mennonite regions and Wiebe mused that this record-keeping and the abundance of written materials is deeply rooted in the Mennonite identity.

“There was a sense in the earlier Mennonite communities that if you want to become a Christian then you must read the Bible, and really learn your Christian faith from the original document. In the book Martyrs Mirror, there are all sorts of stories of early laypeople defending the Bible and knowing the scriptures thoroughly. There was a huge encouragement to learn and study the word yourself, so there was then high value placed on literacy, with people dragging their books along as they migrated, and they would write their own books too.”

Despite this strong cultural connection to the past, the volunteers worry about who they will pass on their work to. Many of the volunteers are in their 80s and they say there’s too much work to keep up with.

“We were about 10 years behind before COVID happened,” said Kathy Braun, “now it’s more like 15 years.” MHSS say they need more volunteers, particularly younger people who are more adept at digital work.

Complicating matters further, some of the rooms used for the archives are no longer available, so volunteers have been hard at work moving materials, downsizing and finding new homes for many of their items. The lack of new, younger volunteers also raises concerns about whether future generations will value these archives in the same way, especially as church attendance shrinks and understanding of what it means to be Mennonite changes.

How to pass these memories and stories along for the future is a big worry for Lorene Nickel: “I’m really concerned about losing all that knowledge . . . of all these memories and history that I know being lost when I die. My son is just asking questions now at 60. I suppose if you read and read and read, you could get that back. I’ll write my family story…starting tomorrow!” she exclaimed.

Still, the volunteers are hopefully imagining the future of the archives. “We’d love to have the funds to hire an archivist to manage and grow the collection, and it would be great to have a research space for people who come in and want to have a quiet, private space to look through the materials,” said Nickel.

Ultimately, it is the preservation of memory that inspires the work of MHSS and keeps the volunteers going.

“To some people it’s not important at all, just live in the present and the future will be whatever it will be,’’ said Wiebe. “But we’ll have a record. We can connect them to other people of their faith. So much of being Mennonite is about the community aspect. We can give future people a sense of what was important for them and valuable for them. We do this so that in the future they will not be forgotten.”

Mennonite historical societies near you

- Mennonite Historical Society of British Columbia

- Mennonite Historical Society of Alberta

- Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan

- Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society

- Mennonite Historical Society of Ontario

- Société d’histoire mennonite du Québec

Not all of the groups maintain archives. Other activities include event planning and publication of written materials. The Mennonite Historical Society of Canada (www.mhsc.ca) serves as a sort of umbrella organization for these and other Mennonite organizations.

The Mennonite Heritage Archives in Winnipeg serves as the official repository for numerous conferences and organizations based in Manitoba.

For discussion

- Does your family have a collection of old photos and written records? How far back does it go? How organized is it? Where is it stored? Who has access to the collection?

- Vic Wiebe believes that record-keeping and having lots of written materials is “rooted in the Mennonite identity.” Do you agree?

- The volunteers of the Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan “worry about who they will pass on their work to.” Do you think interest in Mennonite history is waning?

- The Mennonite church has become more complex over the years, including a greater variety of cultures. How does this change the collection of and interest in Mennonite history?

- What do you think is the future of Mennonite archives in Canada?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.