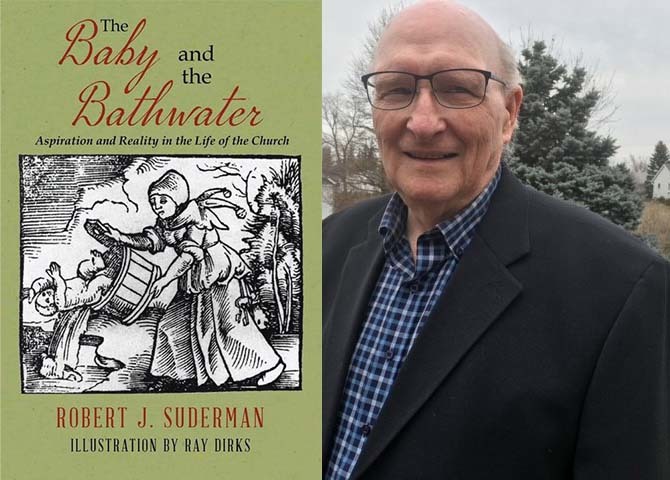

In his new book, The Baby and the Bathwater: Aspiration and Reality in the Life of the Church, Robert J. Suderman, former general secretary for Mennonite Church Canada, makes a case for the importance of the church at a time when its relevance is in question, even by its own members.

Published by MC Canada, and illustrated by artist Ray Dirks, the slim volume is a response to conversations Suderman has had over the years with discouraged church leaders who struggle to articulate the church’s relevance while grappling with its dark history.

While acknowledging the past, Suderman urges readers not to “throw out the baby with the bathwater” because God’s vision for the church is worth holding on to.

Suderman has a long history of more than five decades of work in the church and its varied ministries. This includes teaching, executive administration, international assignment and pastoral training in more than 30 countries around the world. He lives with Irene, his wife of 55 years, in New Hamburg, Ont.

In the following interview, Suderman answers questions about his new book. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What is the motivation behind this book?

Robert J. Suderman: In recent years, a number of discouraged people in the church—college professors, pastors, lay leaders and Sunday school teachers—have told me there is a need for an accessible summary statement of the biblical vision of the church that captures the essence of what it means to be a church in the world, according to a vision that is set out in the biblical record. This book tries to do that but also is an attempt that also asks questions about how are we living up to the amazing vision that is presented to us in the Bible.

Q: You begin the book by examining the expression “don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.” Why is that an appropriate launching point?

Suderman: There are many people that are very discouraged with the church. There’s so much bad stuff about the church—the conquest of Latin America, the crusades into the Middle East, more recently the discoveries of unmarked graves at former, church-run Indian Residential School sites in Canada—really big things where the church was a foundational player and a very oppressive and violent presence. In my conversations with those discouraged folks, the church is largely discarded on the basis of what it has become. My point is that we need to look at what it was designed to be and then see if it should have continued life or not.

This saying of don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater summarizes the dilemma of, when we are discouraged and discontent and even angry at how things are, do we throw it out altogether or do we try to change the bathwater and keep the baby? In other words, in our efforts to deal with the bad, do we also get rid of the good? This saying summarizes that dilemma well.

Q: The 16th-century reformation is such a lauded time for us Mennonites, but you write that we’re in a significant reformation right now. How so?

Suderman: The Reformation challenged how you understood God, the church, baptism, how do you read the Bible, etc. It was never a reformation that was in the process of throwing faith out. It was refining it or trying to make it better or different. Today the very foundational aspects of Christian faith are in question. The question is now why do we need a church at all or is there a God at all, or why do we think Jesus continues to be important? It’s a more profound and dramatic foundational shift of conversation and understanding.

Q: Sara Wenger Shenk, in her new book Tongue-Tied: Learning the Lost Art of Talking About Faith situates the struggle to talk about faith mostly in white, North American congregations. Would you agree? Do you see us turning towards our siblings in other countries to learn how to not despair about the church?

Suderman: Suspicion of faith and the church is everywhere, not just in North America or Europe, but there are different degrees of it. In Europe, this has been at least a century-long long conversation and cathedrals are empty. The U.S. still has a foundational sense of spiritual presence, but this sense is often significantly skewed, whereas Canada is much more secular, in my opinion. I think there is a tendency towards this erosion in other countries as well, but it takes on different forms. It’s not as far along yet.

Right now, when Canadians look at Colombia or Bolivia, it seems faith there is so much more alive, vibrant, dynamic and creative. People still want to talk about it and can, which is becoming increasingly difficult in Canada. But it’s nothing that we can’t also be. The question is whether we want to. Increasingly people are saying it’s not worth it because the church has been on the wrong side of history for too long.

Q: In the first chapter you look at the parable of the wheat and the weeds and how they must grow together. Why is this parable important?

Suderman: From Constantine on, this parable has been used to talk about discipline in the church. For a long time, with the marriage of church and state, everybody was baptized but most people didn’t know much about faith, Jesus or God so there were bad things happening in the life of the church. It needed ways of disciplining vast numbers of people. My point is that if you read the parable carefully, it actually talks about the relationship between those who are committed to follow Jesus and those who are not. How do those two live together? It’s not a question of do we excommunicate somebody or not.

I quote Stanley Hauerwas, a Methodist theologian influenced by Anabaptism. He says, “the first task of the church is not to make the world more just. Rather the first task of the church is to make the world, the world.” In other words, we need to understand that the church is the church and the world is not. That distinction is important. If that is the case, then how do we live together and relate to each other? I think this parable is very helpful for us in thinking through that.

Q: In the introduction you write, “The profound integrity of the biblical call to function in the world as the people of God is really quite simple, yet it continues to be very penetrating.” What is that simple call and why does it become so complicated?

Suderman: It’s simple in the sense that the vocation of the church is to be the church. That’s what God wanted from the beginning, to have a people that were an agent of God’s intentions in every way you can imagine. It’s important to be extremely clear about the foundational intent and to keep going back to that.

What has happened, especially in North America, is that what the church has become then becomes the foundation of our planning for the future. That is unfortunate because planning and strategizing for the future should not be based only on what the church has come to be, it should also be based on what the church is meant to be. It should be based on vision or aspiration not simply on reality. We have to keep that vision alive. We have to keep on saying: it does make sense, if you look back to the way it was designed. It’s holistic and integral. Go back to that intent and the church is supposed to be an agent for justice. You don’t have to debate that, what you have to debate is what does justice mean and how do you do it in this instance. It’s simple on one hand, on the other hand it’s very complex.

Q: Can you say more about God’s vision for the church?

Suderman: God’s vision is so overwhelming that by and large we haven’t known what to do with it. In my chapter called “96 Images,” I explore the lengths biblical writers go to paint creative pictures of what it means to be the church. One scholar says there are 96 creative, dynamic pictures in the New Testament alone—from being a temple, to being a wheat field, to being a boat, to being an arc, to being a light, to being a living letter, to being an odour—and they are designed to function together as a system. Yet most people have no idea beyond a few basic ones, such as the church as a family or a body.

We personally or denominationally choose our favourites and then we generate division and conflict because others choose differently. I suspect your discernment and you suspect mine. But there are 96 ways of being and all of them together begin to create this picture of what the church is designed to be. It’s an amazing picture. It’s too rich to let go of, too rich to lose. It’s hard to imagination or to find a system that is more comprehensive and more creative and more inspiring than this one. But as long as you keep looking only at the pieces, it’s not inspiring at all. That way, it always seems inadequate.

The vision for the church as portrayed in the Bible is absolutely amazing and complete. It’s a vision that continues to have value and relevance and pertinence for our modern life. To disregard it, to ignore it, to not understand it or to throw it out is a big sacrifice for humanity, not just for the church but for the world because it’s an all-encompassing vision that includes justice, peace and anti-oppression. Whatever issue is on the table, this vision of the church presented in the Bible speaks to it in exciting, creative ways.

The Baby and the Bathwater is available to buy or borrow from CommonWord. Current pastors in MC Canada and MC USA can request a free copy. You can watch the recent launch event for the book, held in Winnipeg at CommonWord, on YouTube.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.