It used to be that the tinsel and lights of Christmas didn’t dare emerge until the black cats and orange pumpkins of Halloween were stripped from the shelves. But this year I saw Christmas trees in early October! We had not even given proper thanksgiving for the harvest before boughs of holly decked the halls, enticing us into a winter wonderland.

I resent this headlong rush into the Christmas season. It frenzies my spirit when I long to linger in the dying days of autumn. So I was resentful when I found Isaiah 9, traditionally a Christmas Eve text, listed as the scripture reading for today: “For a child has been born for us. A son given to us.” Good heavens, even the narrative lectionary has succumbed to “the Christmas creep.”

Yet as I pondered this text, I was reminded that the prophet Isaiah did not write with the nativity scene in mind. Nor did New Testament writers refer to Isaiah 9 as a prophecy of the Messiah. In fact, our automatic association of this text with Jesus’ birth probably comes from Handel’s Messiah: “For unto us a child is born.”

Isaiah, however, was speaking very particularly to his own people almost 800 years before the birth of Christ. It was a time of great fear. In Isaiah 7:2, we read: “[T]he heart of Ahaz, king of Judah, and the hearts of his people, shook as the trees of the forest shake before the wind.” Assyria was a rapidly growing empire, and Judah was clearly within the thirsty sites of this colonial power. Aram and the northern kingdom of Israel were also under grave threat, and their kings first asked, then demanded, that Judah join their coalition to fight Assyria. When King Ahaz refused, Aram and Israel declared war on Judah.

Judah was now threatened on two fronts, and into this complex interplay of imperial power, God sent Isaiah to tell King Ahaz to stand firm; Judah should join neither the Assyrians nor the Aram/Israel coalition. “Standing firm” was rather risky advice for a little nation in the face of a two-pronged military threat, so God gave King Ahaz a sign—a baby. Pointing out a pregnant woman, Isaiah said, “Look! Before this woman’s baby can tell right from wrong, the threat of the coalition will have passed.”

Just in case people missed it, God gave the same sign again in Isaiah 8. This time, Isaiah and his wife were going to have a baby, and before that baby grew old enough to speak, the coalition would lose its power.

Then in chapter 9, another child was promised, one who would usher in endless peace, justice and righteousness.

If I had been King Ahaz at the time, I’m not sure that babies would have been much comfort. I can just imagine how Isaiah’s words must have sounded to Ahaz: “Are you and your people absolutely terrified, King Ahaz? Look—a baby! Does it look like your nation is about to be squashed and your people taken into slavery? No worries—check out that baby! Your military strategists can’t figure out how to stave off two different attacks at the same time? No problem—I’m sending you a newborn!”

God has got this thing for babies. In the midst of all the immense, complex political troubles of Judah, God kept offering babies as signs, inviting King Ahaz to what Alastair Roberts calls “the politics of the child”: politics centred on trust, vulnerability and long-range vision.

God was telling the people of Judah to embrace a political stance that was not rooted in imperial power. While many nations were amassing weaponry and troops, with the assumption that the most powerful would take all, Isaiah puts before Ahaz the wildly impractical suggestion that Judah should rather trust in God. Like infants, the people are utterly dependent on God’s provision and care.

I believe that most of the things to which God calls us are both deeply personal and profoundly political. On a personal level, this text calls us, like King Ahaz, to a deep acknowledgment of our powerlessness. Realizing our infant-like reliance on God is both entirely terrifying and fully freeing. As Richard Rohr says, “We are being utterly and warmly held and falling helplessly into this scary mystery at the very same time.” We are each personally called into this deep spiritual journey of dependence upon God.

And what does it mean politically? It means we make the radical claim that God is already at work in the world, moving with power and purpose. Mark Douglas puts it this way: “For the first political act of Isaiah’s theology is to see the world and its politics differently: not first of all as a field of heroic struggle against an overwhelming force . . . or a prison in which humans are stoically trapped . . . but as a site of divine activity. There is hope because God is already working here.”

Nothing begins or ends with us. This is profoundly humbling, and profoundly hopeful.

Now, if that is the first personal and political premise—that God is already at work with great power—then it is possible to believe new things and work toward seemingly impossible goals. That is precisely what Isaiah called King Ahaz to do. While nations around Judah operated in the politics of imperial control, Isaiah called the nation of Judah to centre its politics on the care of the most vulnerable. It was to bring justice and peace, remove yokes and burdens, and break the rods of oppression. In offering Ahaz the sign of the baby, God told him that the priority of his government must be caring for the most vulnerable people among them. This was a radical departure from the politics of dominance.

Personally, we are called to a change of heart, to careful listening and compassionate tending to the vulnerabilities of others. We are invited out of our self-absorbed lives into the care for, and empowerment of, others.

Politically, this priority of the vulnerable certainly has idealistic appeal. But is it a practical political approach? Is Isaiah’s demand of King Ahaz grounded in reality? Can we really ask our poli-ticians today to play by radically different rules?

Well, in Alberta, the City of Medicine Hat decided to give this a try. In 2009, it pledged to eliminate homelessness in its city. In the face of much scepticism and some active opposition, new housing was built that gave permanent shelter to more than a thousand people. Now, whenever people find themselves without a home, the goal is to give them a permanent roof over their heads within 10 days. The mayor, who was initially an active opponent of this plan, reports that the city has had more success than it ever imagined, with unforeseen benefits for the entire city.

What might Isaiah’s politics of the child and prioritizing the care of the vulnerable mean in our own neighbourhoods, towns and cities? What if we directed our imagination and creativity to this task?

Finally, the politics of the child broadens our perspective; it is politics with a long-term view. When we cradle babies in our arms, they often jolt us out of our preoccupation with current needs, to a concern with what we will leave behind for the next generation.

Both personally and politically, this requires the transformation of our desires and calls us to a holistic, long-range vision. Perhaps we see this most clearly when we look at climate change, and the cost that future generations will bear for the choices we make today.

I will not forget the day when one of my children pondered the polluted world, looked me in the face, and said, “You made this mess. You clean it up.” Our children ask us to make intentional choices: To personally develop more sustainable practices, to call our political leaders to green policies, to make the grinding long-term commitments toward a healthy world for generations to come.

When Isaiah held babies before King Ahaz, when we hold our babies in our arms, we are called to remember and live out these politics of the child; to acknowledge our powerlessness and trust in God; to care for the vulnerable; to commit to a long-range vision. This Isaiah 9 scripture is a radical personal call and a profound political vision.

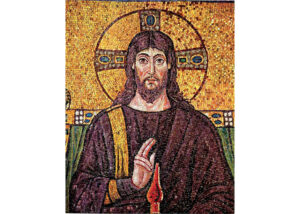

And you know, while Isaiah was speaking to his people 800 years before the birth of Christ, it turns out that he caught God’s drift pretty well. Centuries later, when Jesus was born, the politics of the child were still exactly what God meant. Jesus was thick into both the personal and the political; and trust, vulnerability and long-range vision were central to his message and life.

“For a child has been born for us, a son given to us.” May this challenge and change us.

Judith Friesen Epp is a member of the pastoral team of Home Street Mennonite Church in Winnipeg.

For discussion

1. What do you think is the appropriate time for Christmas decorations and Christmas music to appear? Why do some people welcome signs of the Christmas season while others say “not yet”? Do you look forward to Christmas celebrations with joy, or is your anticipation mixed with anxiety? How is this year different from other years?

2. Judith Friesen Epp writes that, when Judah was under threat, God sent Isaiah with the sign of a baby. What do babies symbolize that makes the sign of a newborn seem like an inappropriate sign and yet also suitable for this situation?

3. Friesen Epp says, “This text calls us, like King Ahaz, to deep acknowledgment of our powerlessness.” What are some of the things that we wish we had power over? Have you had an experience where you had to recognize your powerlessness and depend on God? Do you agree that this is “both entirely terrifying and fully freeing”?

4. How are we doing as a nation in caring for the vulnerable among us? As we enter the 2020 Advent season, what is God’s message of the child for us today? Where do we need to have “trust, vulnerability and long-range vision”?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.