“Talking about ‘a’ Mennonite identity seems passé,” wrote Marlene Epp in 2018. Still, Epp, a member of a pre-eminent family of Mennonite historians, is more than willing to talk about Mennonite identity.

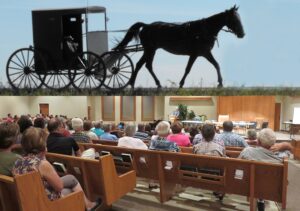

Discussion of what holds us as Mennonites together does indeed seem clichéd. And impossible. We range from buggy drivers to prominent politicians. Our surnames range from Wiebe to Wenger to Abede, as in Deselagn Abede, president of Meserete Kristos Church in Ethiopia, the largest Mennonite body in the world.

Despite the complexity of our diversity, people are eager to return to the old question of identity.

Recently, nine of us at my church—Pembina Mennonite Fellowship in southern Manitoba—did just that. Responses varied, but as people spoke about family histories, learning early Anabaptist stories in Sunday school, more-with-less, and conscientious objectors (COs) they knew, the conviction in their voices struck me. Everyone has a story to share.

And, of course, we talked about last names, the telltale, and often messy, dividing line between people of Russian or Swiss ethnic lineage and people who choose to be Mennonite.

Michael Pahl (not Pauls), fits into the latter category. While teaching New Testament at Prairie Bible College in Three Hills, Alta., and working on a doctorate in theology from the University of Birmingham, he came to the realization that his beliefs aligned most closely with Anabaptism, which he learned about in a church history course.

Now he pastors Morden Mennonite Church in southern Manitoba.

His primary allegiance, he says, is to Anabaptist beliefs more than the Mennonite church per se. For him, those beliefs centre on commitments to Jesus, community and peace. We put Jesus at the centre of our reading of Scripture, and our ultimate allegiance is to Christ, not Caesar or worldly powers, he explains. As for community, Pahl gives Mennonites high marks for being caring, challenging and egalitarian.

The commitment to peace is where things become a bit more hazy. It goes back to the 1500s, when some—not all—persecuted Anabaptists returned good for evil. They eschewed the sword and professed love for their enemies.

Later, that turned into a refusal to participate in war, at least by a significant number of Mennonites. But, since the COs of the 1940s, the emphasis on peace has become less prominent and less focused, with definitions of peacemaking broadening to include a range of social-justice and conflict-resolution measures.

For Sandy Plett of Pembina Mennonite, peacemaking is at the core of the Mennonite focus on stewardship, creation care, justice and service. She names it as one of three Mennonite distinctives, along with service and simplicity. For Plett, this grows out of years of study at Mennonite schools, volunteering with Mennonite Central Committee abroad and in thrift stores, and work with Mennonite camps.

Abe Warkentin is part of a group behind a CO monument and statue of Dirk Willems at the Mennonite Heritage Village Museum in Steinbach, Man. Willems, who escaped from the prison where he was held for his Anabaptist beliefs in 1569, famously turned back to rescue his pursuer, who had fallen through the ice of a nearby pond. Willems was recaptured and later burned at the stake.

Warkentin sees Willems’s example of “returning good for evil” as an iconic example of Jesus’ “way of peace.” He is concerned that Mennonite churches are losing this peace message.

Marlene Epp, a professor of history and peace and conflict studies at Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo, Ont., also talks about the stories from the 1500s—stories of persecution, believers baptism and separation. In an interview, she said that, while a definitive Mennonite “core” is increasingly elusive, what is shared is a collective “memory of origins,” even if those old stories lead us in different directions.

For Epp, the peace position is complicated, as it has often not extended to violence against women, corporal punishment, racism and anti-semitism.

She also notes that Mennonite orientation largely centres on the congregation, and that can sometimes prevent us from looking more broadly. Sharing stories with Mennonites abroad—particularly through Mennonite World Conference—and with non-Euro-Canadian Mennonites in Canada has expanded the sense of Mennonitism.

While pinning down a definitive set of Mennonite beliefs is fraught, perhaps we can at least identify the tensions and questions on which much of Mennonite identity has centred. How do we follow Jesus practically? (Service is a word we use a lot.) How do we navigate the tension of being “in the world but not of the world”? (Here lie questions of technology, simplicity and separation.) How do we deal with power, both among ourselves (priesthood of all believers) and when the world threatens (non-resistance, separation of church and state, and love of enemies, if we still have those)?

For Epp, the task is not to nail down answers, but to bring a curious and compassionate ear to the great diversity of stories that swirl around them.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.