Toronto United Mennonite Church was the first church in Canada to receive privately sponsored “boat people” who were fleeing Vietnam and Laos during the chaos of the Vietnam War.

Early in March 1979, an adult social-issues group meeting during the Sunday school period took the first step. The story of Southeast Asian refugees fleeing by boat had hit the headlines. Soon, Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) stepped in to propose and secure a sponsorship agreement with the Canadian government that would allow private individuals and groups to sponsor refugees. MCC and the Government of Canada signed the agreement on March 5 of that year.

As church members watched TV reports of harrowing rescues of boatloads of Vietnamese people, or others waiting behind fences in refugee camps, we remembered the flight from oppression many of our own parents and grandparents had experienced in the past. We wanted to save the lives of as many people as possible.

Our church was ripe for a new project. With a copy of the agreement, a group began to organize. Harvey Dyck became the chair of the Southeast Asian Refugee Committee, and soon an overall philosophy and approach to a refugee-aid program was worked out.

Next thing we knew, a CBC-TV news crew was filming a refugee-aid committee meeting in the church’s “upper room,” as we discussed ways and means to sponsor these refugees.

Our first refugee family arrived in April 1979. Over the next two years, almost everyone in our hundred-member congregation was involved in the program. By the end of that period, our church had accepted and settled 49 Southeast Asian refugees in 13 groups ranging in size from one person to families of seven members.

Church members also stimulated interest in sponsorship through the media, speaking to other churches and lay groups in the city, and inviting neighbours and friends to get involved. In this way, our church became the formal sponsor for a further 22 refugees undertaken by other Toronto groups: a student and staff group at Wycliffe College, a Mississauga family, a University of Toronto group and a group of schoolteachers. Three other Ontario Mennonite churches—Berea Mennonite Church near Drayton, Dunnville Mennonite Church and the Mennonite Fellowship that existed at that time in Brampton—became our partners.

MCC provided our church with advice on access to government-assistance programs and resources, in part by employing the invaluable Tinh Huynh, a Vietnamese man fluent in English who acted as interpreter and consultant. Along with our church volunteers, he went to Toronto Pearson International Airport to meet refugees and take them to local hotels. Later, he helped them find apartments. He assisted in orientation, visited them, and explained how to navigate the city to find donated clothes and furniture, or the city’s Chinatown. As interpreter, he and our volunteers accompanied refugees to Canada Manpower (as it was known at the time) to help them find jobs, to doctors’ offices, and to schools to help them register their children.

At the outset, the aim of church sponsorship was not to overwhelm one family with loving care and encourage dependency, but to help as many desperate people as possible.

This policy was clearly explained to the refugees: that the house shelter was temporary and that our church group would assist them to adapt to Canadian life and to become self-sufficient as soon as possible. As a chair of the refugee-aid committee wrote, “The approach is based on Anabaptist-Mennonite principles of Christian love, corporate responsibility, mutual aid and decentralization directed to settling as many refugees as limited funds allow. ‘More with less’ is our watchword.”

Our settlement program excited nearly everyone in the church. It bloomed into committees and sub-committees. An early task was fundraising, and a big-budget item was housing. Because hotels were costly and the first family of seven was large, the congregation and refugee-aid committee decided to buy a seven-room house to be used for temporary housing. The price is hard to believe today, but in May 1979 the congregation approved the purchase of a house at 424 Jones Ave. for $35,000. The money came from interest-free loans given by members and friends. When all our refugees had secured their own permanent housing, this house was to be sold and the loans repaid to donors. By the end of 1980, two years later, the families had permanent housing.

The support policy is illustrated by the example of the Luong family. The seven-member family settled into the house at 424 Jones Ave. Another family, the Huang family, consisting of mother, father and three children, shared the house. The Luongs, two parents with five children, were given a base support of $600 a month. Of this, $270 was considered rent, and a first payment of $330 was given to the family. As Family Allowance and earnings came in, and family members started getting jobs and earning money, these sums were deducted according to a set rate. In a short time, the support money was freed to assist another family.

The Luongs were eager to earn their own money and to make their own choices of food, clothing and shelter. One month after their arrival, both parents had been initiated, with language school for the mother and a factory job for the father, who spoke some English already. One son found a job, and within six months the family income was sufficient for them to move into an apartment of their choice. Congregants helped to find their new place, provided furniture and household equipment for their chosen apartment, and helped with the move. A new refugee family moved into 424 Jones.

Because our refugees came largely from urban backgrounds, we were confident they would soon succeed in making their way in Toronto, a city offering varied educational and job opportunities and quickly a growing Southeast Asian communities. With our relatively modest funds and many volunteers, we provided emotional support; housing; winter clothing; orientation to access health, school, government assistance; and initial individual financial services. Once education and jobs got one group of refugees on its feet, it made room for another group.

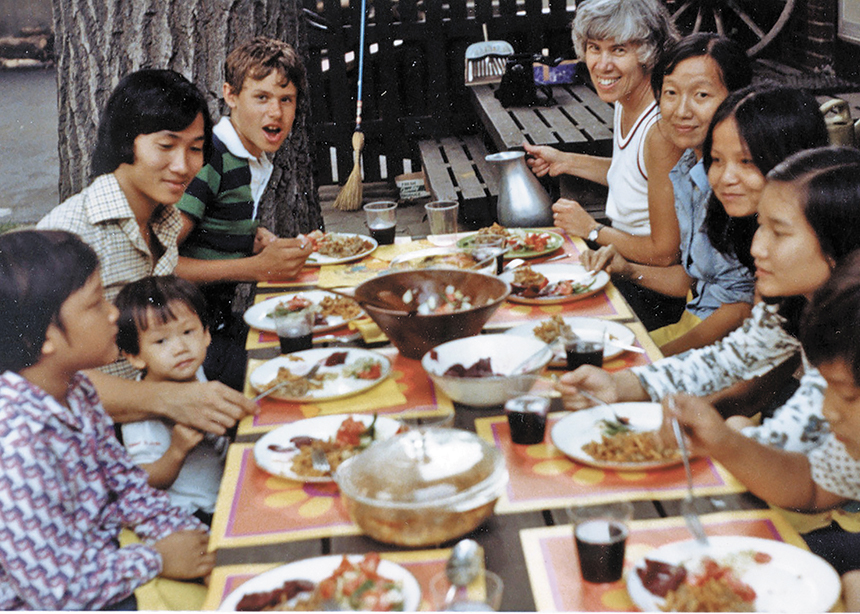

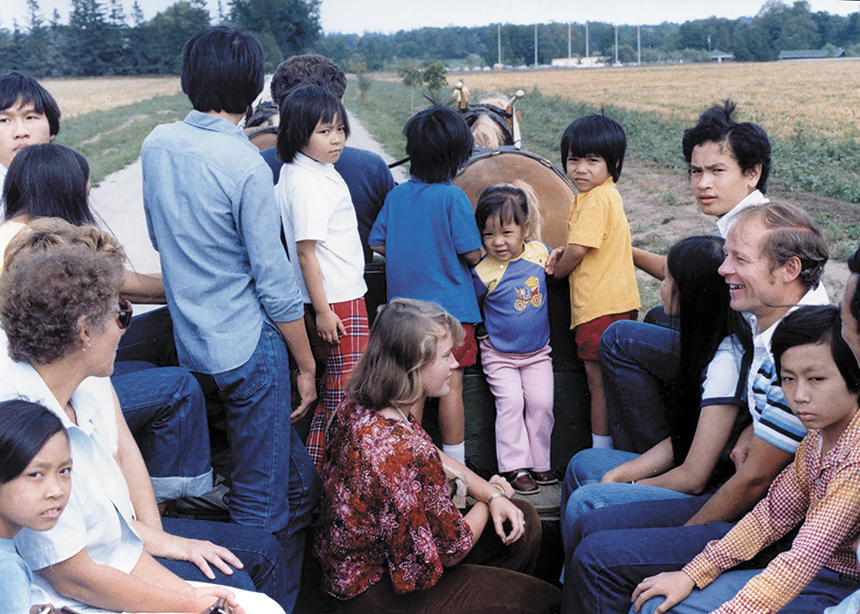

Our congregants were active in many other practical ways, such as doing repairs and improvements to the settlement house. We helped with orientation, airport pickups, taking refugees to school, language classes or doctors, and training them in how to use public transportation. Congregants also spent informal time with our guests: on wagon rides and at potlucks and wiener roasts. For the first 23 refugees, we organized a welcome picnic along with members from the Dunnville, Berea and Brampton Mennonite congregations, as well as Toronto Evangelical Vietnamese Church.

At that time, the refugee-aid committee also reported “with gratitude” that $30,000 had been committed to refugee work. This, along with the self-sufficiency policy, allowed the church to sponsor so many refugees.

Any family member able to work was encouraged to take a job and help the entire family to become self-sufficient. Our refugees agreed readily to the emphasis on self-sufficiency and independence. The bare-bones approach allowed the committee to settle a total of 70 refugees!

Darrell Fast, our pastor at the time, along with the church board, worked with the refugee-aid committee to make the refugees feel welcome. Winfred and Jean Soong, then pastor of Toronto Chinese Mennonite Church and his wife, also helped with interpretation and welcomed refugees into their church, which some attended and later joined. Toronto Vietnamese Evangelical Church became a church home for some others.

As our church gained experience and saw that the refugee program was going well, we broadened our scope. In addition to the families we had committed to sponsor, we helped rural churches in their sponsorships, with those churches providing the funds. We also helped a local Vietnamese family to foster a set of four brothers.

Summarizing the benefits of the refugee project, in his 1979 annual report Harvey Dyck noted that the church budget had not suffered in the least. According to him, the settlement outreach had strengthened the spirit of cooperation among church members, attracted new friends, gave children and youth a lesson in practical Christianity, and helped broaden church members’ perspectives beyond a “me first” ethic.

As a church-partner family wrote in December 1980: “Our refugee family are now living full, busy lives in Canada, taking English classes at night, the children enjoying our customs. They are no longer refugees, but immigrants, and we have been privileged to have this opportunity of sharing their resettlement here.”

Anne Konrad Dyck was an original member of the Toronto United Mennonite Church Southeast Asian Refugee Committee.

Beyond the ‘boat people’

With Files by Evan Heise

Toronto United Mennonite Church

The first concerted refugee-settlement initiative by Toronto United Mennonite Church was the welcoming of refugees fleeing Southeast Asia in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Soon, Mennonites in Canada began responding to refugees from Latin America. In Toronto, this resulted in the establishment of the Mennonite New Life Centre and Mennonite New Life Church, with whom Toronto United Mennonite still shares its building.

By the late ’80s and ’90s, our congregation, in collaboration with the Mennonite New Life Centre, helped settle families from Latin America, the former Yugoslavia, Somalia, Liberia, Iraq and others.

In 2009-10, along with Mennonite Central Committee, our congregation responded to an appeal from the Canadian government to assist with the sponsorship of Palestinian refugees from a camp in eastern Syria. Along with three other congregations in the Greater Toronto Area, we welcomed two families and fully paid for their first year of life in Canada, walking with them through their adjustment.

Through the government-sponsorship option, called Blended Visa Office-Referred, especially vulnerable refugees are identified. Our church participated in two such sponsorships, the first in 2013, with two, young, single Eritrean men who had grown up in a refugee camp in Sudan. The second was in 2017, with an Iranian family that had been hosted by Turkey for eight years as part of the Syrian crisis.

In 2018, we undertook a full sponsorship of a young man from Eritrea via Israel. He is now working full-time for a heavy-equipment manufacturer in Guelph, Ont., and looks forward to sponsoring his wife on his own next year.

This year, we responded to a financial appeal by a church member to assist with a Syrian refugee family that is being sponsored by another group he is a part of. Our church expects to welcome six Eritreans—young women and children—sometime this summer.

For discussion

1. Do you know people who fled Southeast Asia and came to Canada in the late 1970s and early ’80s? Where are these people now? What services were important to integrate them into Canadian society? Through what process did some of them become part of the Mennonite church?

2. Information about Mennonite Central Committee Canada’s agreement with the government regarding refugee resettlement appeared in the April 1, 2019, issue of Canadian Mennonite. It was signed on March 5, 1979, and Toronto United Mennonite Church welcomed its first refugees in April of that year. What does this timeline show about this congregation? Did other congregations respond in a similar way?

3. Toronto United Mennonite helped as many people as possible, encouraging newcomers to quickly become self-sufficient. What are the advantages or challenges of this approach? In what situations might this strategy be particularly difficult?

4. What part of Toronto United Mennonite’s refugee sponsorship story do you find most inspiring? Where are the refugee crises today? Who is stepping up to help? What are some ways that congregations can work collaboratively to be more effective?

—By Barb Draper

Further reading:

Consider it (re)settled

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.