The year 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. According to tradition, Martin Luther posted his 95 theses on Oct. 31, 1517, thereby starting the chain of events that gave birth to the Protestant churches and destroyed the unity of western Christianity.

The anniversary, no doubt, will be filled with celebration and mourning. Protestants can feel gratitude for the faith of those who proclaimed the good news of God’s free and unfettered grace. At the same time, those who proclaim “one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Ephesians 4:5) cannot fail to see the tragedy in the division of the body of Christ.

At the risk of making superficial comparisons with the past, there are some similarities between 2017 and 1517. Just like Luther and his followers, we also live in a time marked by economic and political uncertainty and unease exacerbated by new forms of media. Perhaps we can follow Pope Francis’ lead in seeing the commemoration of the Reformation as an opportunity to reject division and despair when he marked the milestone with members of the Lutheran World Federation at Lund Cathedral in Sweden last year.

In a generous ecumenical spirit, Francis praised Luther for restoring Scripture to the centrality of the church and his reminder that we are saved “by God’s grace alone.” The pope also called on the year’s coming commemorations of the Reformation of 1517 to be an opportunity for Lutherans and Catholics to work towards greater unity and cooperation. The ecumenical prayer service was the first time that a pope commemorated Reformation Sunday with a sermon “recognizing error and seeking forgiveness” for the divisions of the past.

The service at Lund was a symbolically momentous expression of ecumenical hope, building on decades of careful historical and theological reflections on the divisions between Lutherans and Catholics. Vatican II (1962-65) affirmed that elements of truth and sanctification can be found outside the Catholic Church. It also accentuated the traditional Protestant emphases of the importance of Scripture, the priesthood of all baptized believers, and the need for the church to continually purify and reform itself.

Following 50 years of ecumenical dialogue, Catholic and Lutheran theologians issued the “Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification” in 1999, which outlined their shared convictions around how humans are saved. The recent publication, From Conflict to Communion: Lutheran-Catholic Common Commemoration of the Reformation, ends with the observation that “the struggle of the 16th century is over” and gives five imperatives for securing greater Christian unity.

At the conclusion of his homily in Lund, Francis challenged those gathered with these words: “We Christians will be credible witnesses of mercy to the extent that forgiveness, renewal and reconciliation are daily experienced in our midst. Together we can proclaim and manifest God’s mercy, concretely and joyfully, by upholding and promoting the dignity of every person. Without this service to the world and in the world, Christian faith is incomplete. As Lutherans and Catholics, we pray together in this cathedral, conscious that without God we can do nothing. We ask his help, so that we can be living members, abiding in him, ever in need of his grace, so that together we may bring his word to the world, which so greatly needs his tender love and mercy.”

Differences remain

There are still many differences in practice and doctrine between Anabaptists, Protestants and Catholics, such as the role of women in the church, Mary, communion, baptism and nonviolent discipleship. Nonetheless, Mennonites should seize this opportunity of historical reflection to share their gifts with other traditions and receive the gifts that they can offer in turn.

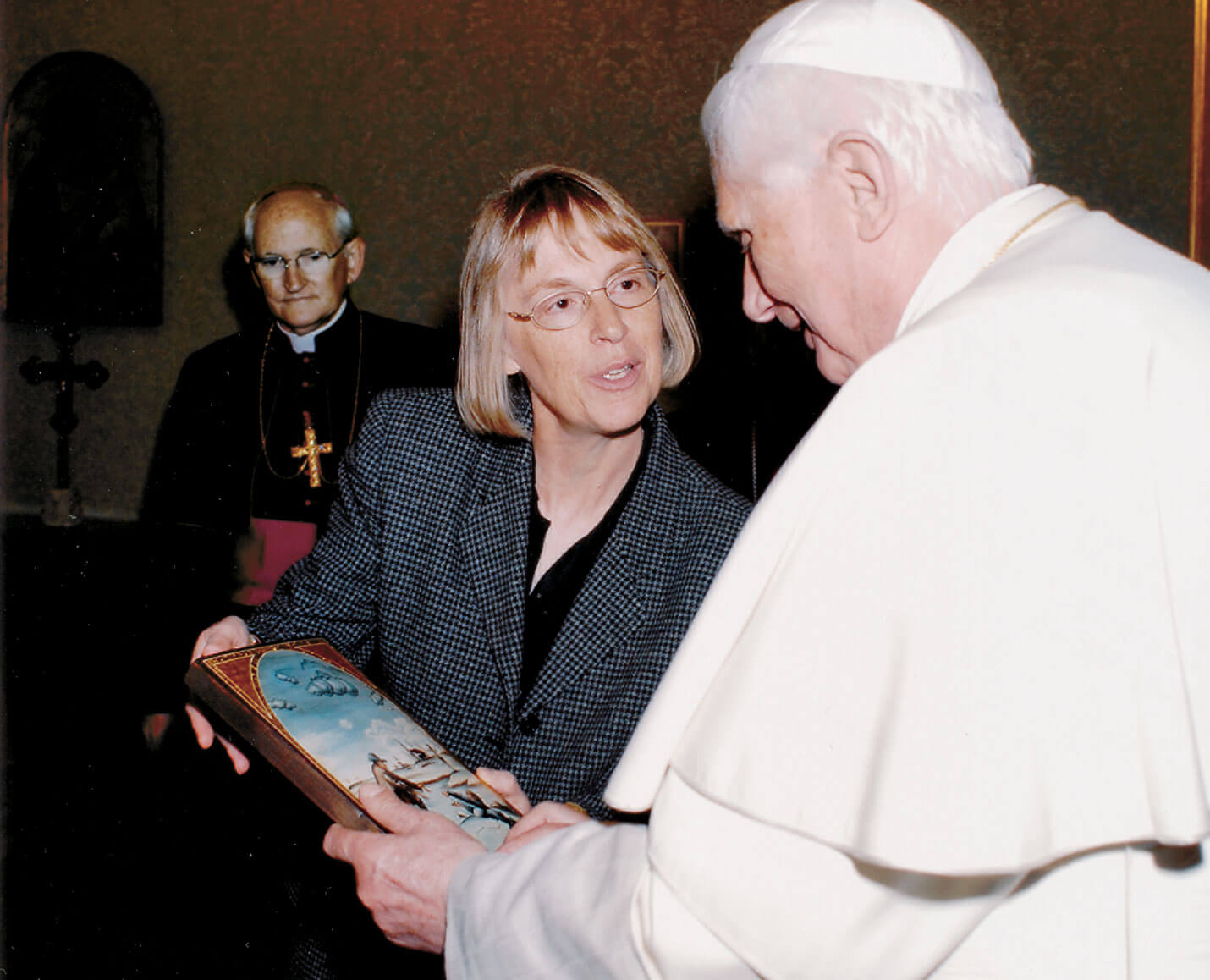

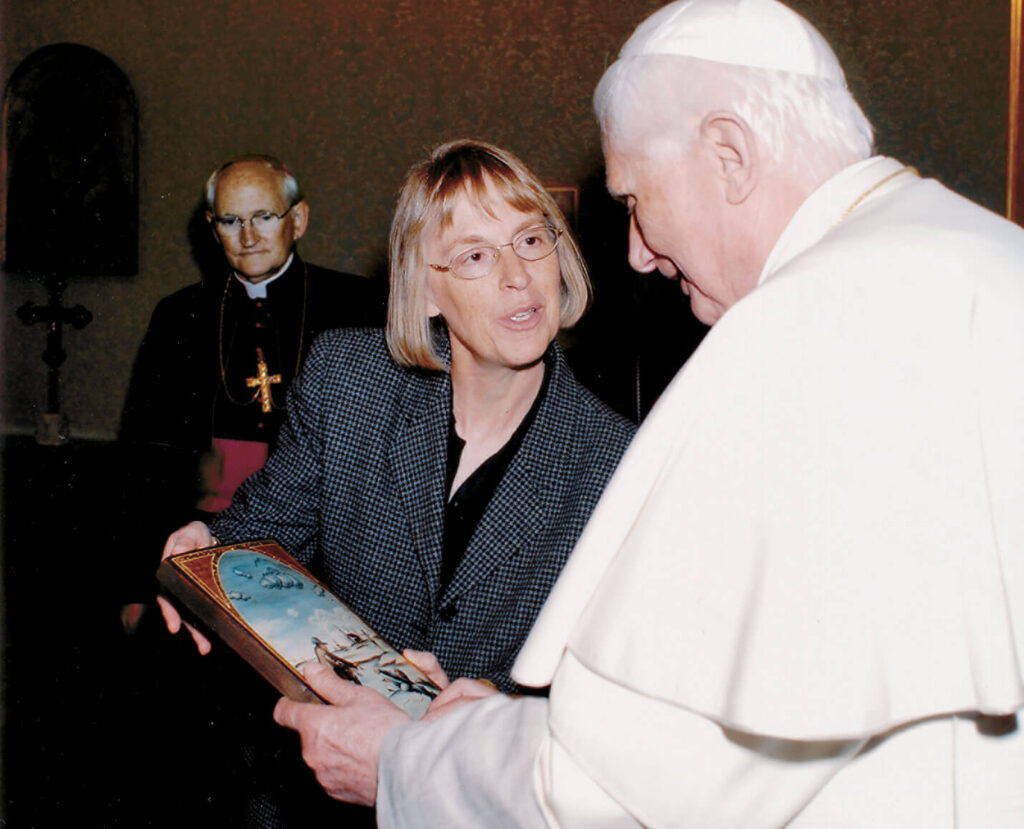

Representatives of Mennonite World Conference (MWC) have also met with their Lutheran and Catholic counterparts over the years to study their history and theological convictions for potential areas of greater inter-church cooperation.

In 2004, the Lutheran World Fellowship and MWC called for the “right remembering” of the Reformation after Lutherans issued an apology for the ways that Lutheran authorities persecuted Anabaptists in the past. They also re-evaluated the condemnations of Anabaptists in the 1530 Augsburg Confession.

In February, MWC will hold the first session of Renewal 2027, a 10-year series of events to commemorate the beginnings of the Anabaptist movement. The commemorations are scheduled to be held in Germany, Kenya, Latin America, Western Canada and at the 2027 MWC assembly, possibly in Switzerland.

Mennonite commemorations and dialogues, like those of the Catholics and Lutherans, call for a fresh reading of the history of the Reformation and stress the importance of healing the memory of those tumultuous events. It is striking that all of the organizers view the commemoration of the Reformation as an opportunity to take a self-critical view of the church and faithfulness in the past and the present. The need to re-examine the past arises from the fact that the identity of contemporary churches is often based on outdated or inaccurate memories of other churches.

At the same time, many of the events that fractured the church in the 16th century are essentially unknown to many believers today, a fact that strikes me when I teach the history of the reformations to 18- to 21-year-olds. As From Conflict to Communion succinctly states, “The task is not to tell a different history, but to tell the history differently.” Nearly all of this year’s commemorations and ecumenical statements reject confessionally biased history writing for a view that integrates the current state of the historical field.

Luther in a different light

New research on the Middle Ages, for example, covers the period before Luther with far greater nuance. Before the Reformation, the western church was neither as thoroughly fallen as Protestants described it, nor was it the idealized Christian society promoted by Catholics. According to From Conflict to Communion, both Protestants and Catholics affirm Luther as an “earnest religious person and conscientious man of prayers.” Catholics praise Luther’s fundamental question, “How do I find a gracious God?”

Recent scholarship has portrayed Luther as a difficult hero; in addition to a theological visionary, he was a harsh polemicist and anti-Judaist. When he posted his theses in 1517, Luther, a monk at a backwater university, did not intend to start a Reformation nor divide the church. His criticism of the sale of indulgences tapped into a larger movement to reform those practices and tenets of the church that were based on human teachings.

Luther believed that the sale of indulgences and remissions of the punishment of sin damaged Christian spirituality. He wrote that the believer is saved by faith in God’s promises alone, not by works. The individual had direct access to God and did not need the church to mediate salvation. Scripture, he later wrote, was the only authority for the church and Christian life. Luther’s teachings provided the theological justification for the rising pressure on the church to reform itself, and he quickly became celebrated internationally for providing the intellectual justification for reforming corrupted practices. The papacy condemned Luther as a heretic and, in return, Luther burned the edict, also known as a papal bull.

The Wittenberg reformer’s ideas spread in ways that even he could not have predicted or controlled. Luther’s revolutionary ideas spread to Switzerland, France and the Netherlands. The movement begun by Luther later fragmented and divided over differences about whether the bread and wine of communion were the body and blood of Christ.

In 1525, German peasants revolting against unfair legal and economic practices saw in Luther’s ideas support for their calls to reform society according to biblical principles. Rome eventually reasserted the authority of traditional church teachings and papal authority, and cleaned up much of the corruption in the church.

By the end of the 16th century, northern Europe was Protestant. For these churches, Christian faith was no longer about rituals, but it was about agreeing to a series of theological statements. Early on, Luther and other reformers turned to princes and magistrates to help oversee the establishment of the reforms and new church governance. After these authorities helped stabilize and protect the budding Protestant churches, the entanglement with political powers linked denominational identity with national allegiance.

‘New challenges’

The sheer volume of scholarship on the Reformation illustrates how difficult it is to summarize the events of the 16th century, which mean different things to different people. Some of the most heated debates will discuss the long-term effects of the reformations.

For example, Brad Gregory, the American Catholic historian, charges the Protestant Reformation with the creation of a “hyper-pluralistic” society and political polarity. By claiming the authority of Scripture alone, Protestants discovered that Christians could arrive at different conclusions from the same set of verses. The historian Carlos Eire claims that this fragmentation turned religion “into a private concern, rather than a public one,” as western society turned increasingly materialistic and secular.

As From Conflict to Communion correctly states, our current context presents “new challenges” in commemorating the various Protestant, Anabaptist and Catholic reformations. Christianity is growing most quickly in the Global South, where believers do not always see the 16th-century conflicts as their own.

Furthermore, the growth of Pentecostal and charismatic movements have provided new avenues for inter-church cooperation; their emphasis on the gifts of the Spirit make the old divisions seem archaic and irrelevant. In the secular West, many have already abandoned Christianity and forgotten about the issues that divided the church, or why questions of sin and salvation should matter today.

In these contexts, the fundamental question is not about which heir of the Reformation is the correct one, but whether the story of God as revealed in Scripture is fundamentally true.

Troy Osborne teaches history and theological studies at Conrad Grebel University College, Waterloo, Ont. He is a member of Waterloo North Mennonite Church.

To learn about how Mennonite World Conference will be commemorating Anabaptism’s role in the Reformation see “The next 500 years of Anabaptism.”

See also:

Healing Memories: Lutherans/Mennonites

Catholics and Lutherans commemorate Reformation

Mennonite helps Lutherans celebrate the Reformation

For discussion

1. What are the different Christian denominations in your community? How are they different from each other? What things do the churches do cooperatively? Do you see signs of greater Christian unity in the future?

2. The Protestant Reformation brought the idea that Scripture is authoritative, rather than the Pope. Some historians think this led to the idea that religion is a private, rather than public, matter. Do you agree? What are the benefits and disadvantages of regarding religion as private, rather than public? Does private religion play a role in materialism and secularism?

3. Troy Osborne writes about joint meetings of Catholic and Lutheran theologians, and how representatives of Mennonite World Conference have met with other world church leaders. What are the benefits of these meetings? How might the future of the Christian church be influenced by such cooperation?

4. What are the major issues facing the church today? Are the issues of the Reformation still relevant? Do you agree that the fundamental question today is “whether the story of God as revealed in Scripture is fundamentally true”? What has changed in 500 years to make that the prevalent question?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.