“As part of my probation conditions, I have to stay away from places where there are families,” says Joe Patterson, “so that made finding a church hard.”

It didn’t help that when he was released from prison, he stepped into a society primed to fear and revile people like him. Politicians of all parties talk tough about crime, often fuelling shadowy public sentiments in the process. And the media tend to play along. When Patterson got out of prison, a local newspaper printed a full-page photo of him along with his record of sexual offences against minors. The paper’s online comment section teemed with vitriol.

Sitting at the kitchen table of his modest Winnipeg apartment, Patterson speaks without pretension, like someone who does not take for granted a second chance at life.

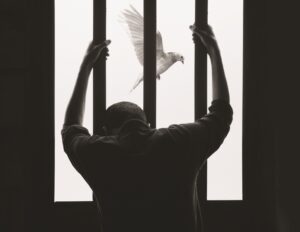

Having worked hard at rehabilitation while in prison, Patterson was eager to start over. But it has not been easy. After his release, any venture out among the public, including attending church, made him nervous. “Part of the challenge in reintegrating is facing the fear that no one is gonna want to have anything to do with me,” he says. But he ventured out and was fortunate to find people of faith who chose courage over fear and welcome over demonization, while still taking seriously the realities of evil.

“We’re not here to judge or condemn anyone,” says Pastor John Woodman of Grace Community Chapel. (Names have been changed and dates omitted to protect privacy.) So when Patterson showed up at the medium-sized Winnipeg church, Woodman considered it a “wonderful” chance to do what the church is called to do: Welcome people. Woodman notes that Jesus was a “friend of sinners.”

Patterson chose the congregation based on the recommendation of a prison chaplain, who accompanied him on his first visit to the church and disclosed his past to the pastor. Although Woodman was immediately open to having Patterson in the pew, the decision to include him—ultimately made by the church council in consultation with parents—took a couple of months. One concern was the desire to show sensitivity to victims of sexual assault. The larger concern was that of the parents.

One parent said initially that he wanted to either “combat” the inclusion of Patterson or find a new church. But over time he realized that everyone needs community. Now he says he is “completely at ease” with Patterson’s attendance and the “healthy boundaries” that have been created. Correctional Service Canada required that two church members obtain approval to supervise Patterson. One of the two has to maintain visual contact with Patterson when children are present.

While he feels like a different person than the one who committed the offences, Patterson says he still chooses to avoid children in the church, partly out of regard for the sensitivities of parents and partly because of his utter determination not to “have any more victims.” He says a broken childhood and a then-unacknowledged mental illness contributed to his offences, but he quickly adds that he takes full responsibility for his actions.

In prison, Patterson recognized that most of his fellow inmates had also suffered deep rejection in life. Their need for love, intimacy and belonging were not met in “normal” ways, he says, so they turned elsewhere. The societal rejection they experience when released makes them more likely to slip into old patterns. That’s why the acceptance of Grace church means so much to Patterson.

A welcome rooted in the gospel

The welcome offered by Grace chapel is rooted in the gospel, not in a need to be politically correct. Woodman says that his congregation is rooted in an evangelical tradition that has long been concerned with drawing lines between who is “in” and who is not. But Woodman asks: “Who gives [us] the right to draw a line? . . . If you’ve come here, you’ve already turned your face toward God,” and—quoting Jesus—“He who comes to me I will in no wise cast out.”

Grace chapel is not alone. In Manitoba, for example, a handful of congregations, including Mennonite ones, knowingly welcome people who have criminal histories. The posture of these churches contrasts with the tough talk favoured by the current Canadian government.

Canada, U.S. moving in opposite directions

In the U.S., the birthplace of the tough-on-crime approach, there are 762 inmates per 100,000 citizens, more than any other country; Canada’s rate is 108 per 100,000. But Americans are slowly realizing that the punitive approach cripples government budgets without making society safer. A 2010 New York Times editorial called America’s tough approach a “failure . . . shaped by fear-driven ideology.”

Even some Republicans, led by Newt Gingrich, a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, are questioning the “lock ’em up and throw away the key” approach that hard-nosed conservatives have long advocated. The website of Gingrich’s Right on Crime initiative states, “An ideal criminal justice system works to reform amenable offenders.” Recognizing that prison often exacerbates, rather than breaks, the cycle of crime, the initiative emphasizes flexible sentencing and treatment programs for offenders.

This new approach is visible in Texas, where officials hope to have 15,000 fewer people behind bars in 2012 than in 2007. Not only will this save Texas a projected $2 billion, it has already contributed to the lowest crime rates in the state since 1973.

Canada, however, is headed in the opposite direction. Since the federal Conservatives took office in 2006, spending on Correctional Service Canada jumped from $1.6 billion to $2.98 billion, an increase of 87 percent. The figure is expected to rise to $3.15 billion by 2013-14, as Bill C-10, the omnibus crime bill, is expected to put an additional 3,600 people in prison. All of this despite the fact that, from 1998 to 2007, the crime rate dropped by 15 percent and the severity of crime by 21 percent, although nearly half of Canadians believe the opposite to be true.

The Circles of Support and Accountability alternative

But what exactly is the alternative to fear-driven ideology? While Grace chapel exhibits a radically merciful attitude towards offenders, that alone is not enough to address what one expert calls “long-term, entrenched patterns of violent behaviour.”

For over 12 years Joan Carolyn has helped people deemed at high-risk to reoffend—including Joe Patterson—make the transition back into society. She offers no easy answers, but a courageous and thorough approach that has proven helpful in some cases.

Carolyn heads the Winnipeg office of Circles of Support and Accountability (COSA), a gutsy little non-profit organization that works primarily with men who have sex-offence histories. Upon release from prison, each of the men, known as “core members,” is surrounded with a “circle” of four to six supporters—mostly volunteers—who meet weekly. To qualify for a “circle,” a core member must show remorse and a desire for help.

The Winnipeg COSA office, which used to be part of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Manitoba, now operates as part of Initiatives for Just Communities, with continued funding and board representation from MCC Manitoba. About 30 volunteers—a quarter of them from Mennonite churches—keep the seven Winnipeg “circles” going. One core member has even become a member of a Mennonite congregation.

Weekly “circle” meetings are designed to nurture healthy relationships—something that may otherwise be absent—through activities like bowling, camping and birthday parties. Sessions also involve candid discussions in which the core member has to own up to the damage he has done, put his “darkest secrets” on the table and face constant accountability, none of which necessarily happens in prison. Volunteers are trained both to be supportive and to identify and report warning signs.

“I feel able to talk about anything,” says Patterson of his weekly “circle” sessions. For him, the basic affirmation provided by his “circle” is invaluable. “You get that negative message from society: ‘I don’t want you,’ ” he says, adding, “COSA has been the opposite.”

Carolyn emphasizes the need to work along side victim-services agencies. The fundamental goal of COSA is, “no new victims,” she says.

Carolyn says the COSA model—which took shape in Ontario in 1994, and has since led to the development of another 15 independent offices across the country—includes collaboration with parole workers, police, treatment professionals, social assistance networks and neighbourhood groups. COSA offices have faith roots, although some have expanded beyond that.

Roots in restorative justice

The COSA approach is based on the philosophy of restorative justice, which was developed largely by Howard Zehr, a professor at Eastern Mennonite University, Harrisonburg, Va. In his groundbreaking 1990 book, Changing Lenses: A New Focus for Crime and Justice, Zehr contrasts retributive justice, which focuses on blame and punishment, with an approach that involves all stakeholders in a process to restore wholeness to victims, offenders and communities.

Although steeped in the restorative approach, Carolyn is quick to point out that the “formal” retributive justice system and alternative systems must work together. In fact, a significant portion of her budget comes from Correctional Service Canada.

A Correctional Service Canada survey found that two-thirds of COSA core members felt they would have returned to crime without the program. And yet some core members do re-offend. “Never underestimate the power of evil,” Carolyn says, while also asserting her belief in the superior power of good.

While COSA is not soft on crime, its toughness respects the inherent worth and dignity of every person. When Carolyn says everyone is “created in God’s image,” she means it.

While the common fear of sex offenders, and the desire to lock up people who pose a risk is understandable, ultimately this approach may be counterproductive. Making a similar point in theological terms, one member of Grace chapel says that, while “isolating and scapegoating” people like Patterson may make us feel better, “it doesn’t raise us, or them, to the potential God sees in us.”

Zehr emphasizes the importance of having a positive, constructive vision in addressing crime, something he says the punitive approach lacks. In an updated edition of Changing Lenses, he writes that restorative justice is an expression of the respect, humility and interconnectedness of all people, as well as an appreciation “of mystery, of ambiguity, of paradox, even of contradictions.”

That mystery is made real every Sunday at the communion table of Grace chapel, where everyone can partake in the broken body of Christ, and where Patterson’s offence matters less than his presence.

“We don’t want to be famous as the church for ex-cons,” says Woodman. “We just want to be the church.”

That’s good news, both for Joe Patterson and for society as a whole.

For discussion

1. How would your church react if a known sex offender wanted to attend regularly? Is this a simple struggle between fear and love—between the realities of evil and the church’s mandate to be welcoming? How can we balance the need to be welcoming and the fear of evil?

2. How would you explain the concept of restorative justice? What role do Circles of Support and Accountability play in restorative justice? What are the advantages and the risks of this approach to wrongdoing?

3. Why do you think the number of inmates per population is so much higher in the U.S. than in other countries? Why do so many Canadians believe the crime rate is increasing in spite of the statistics that show it is dropping? Is the Canadian attitude towards crime changing?

4. How could the church help to foster a more positive attitude towards former inmates? How important is it that they show remorse and a desire for help? How might we encourage more of our congregations to be involved in the work of restorative justice? What would it take for our society to have a restorative justice approach to crime?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.