Are my children going to be okay?” This is the overriding concern that Kathy Giesbrecht, associate director of leadership ministries for Mennonite Church Manitoba, hears and senses from parents. Parents are scared and overwhelmed, and there is no manual for them to keep in their back pocket. If parents a generation ago felt overwhelmed, today’s parents are experiencing changes they could only have imagined when they were growing up.

“The rapid advancements in technology are shaping how our kids are growing up,” says Dave Currie, president of Doing Family Right, an organization that educates and provides counsel on family-life issues. “Parents have to be way more savvy on a lot more things than they used to be.”

The recent recession has heightened insecurities about the future. The competition for university seats is no longer just the student sitting next to their child in the high school biology lab. It’s students in Asia and around the world vying for the same limited spaces. There is pressure to turn out well-adjusted children. There are countless community programs to help, to equip them with skills, to keep them out of trouble, but when struggles emerge, parents stand or fall alone.

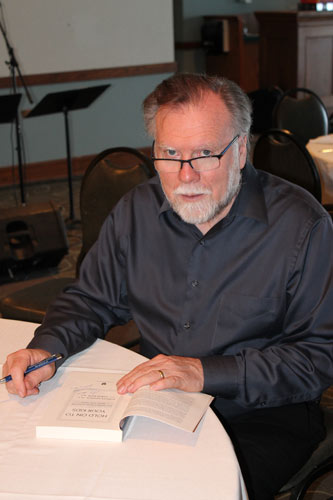

And then there is rampant materialism. Both Currie and Gordon Neufeld, a developmental and clinical psychologist and co-author of Hold on to Your Kids, blame the pursuit of materialism as a significant negative force in the task of parenting. Generations ago it was the Industrial Revolution that had dramatic impacts on family life, Neufeld says. Now, it is materialism. “Today, decisions about money supersede what is best for the family.” He says that working on Sundays and parents moving to where the money is, rather than where the family support network is, reflect that money is more important than culture and relationships.

In some ways it has always been like this for parents, but a new set of challenges and issues have arisen that complicate the task of parenting today beyond what it was only a generation ago. A mother notes that parenting her youngest, who is graduating from high school this year, has presented her with challenges she never faced with her older three children a mere seven years ago, and it isn’t just personality related, she is quick to point out.

New technology challenge

At Menno Simons Christian School, Calgary, which offers classes from Kindergarten to Grade 9, principal Byron Thiessen says that most students, once they reach junior high, have their own cell phones or Blackberries. “Parents are looking for help as to what is appropriate and inappropriate use of technology,” Thiessen says.

Several principals observe that cell phones serve as an umbilical cord for parents anxious to keep that connection with their child, even if it does interrupt their child in class at times.

However, a mother says of her teenage daughter, “The cell phone should be a way I can keep in touch with her, but that’s only an illusion. She has instant contact with everyone, but I have no way to monitor that, and she can conveniently be ‘out of range’ if I need to reach her.” Although her daughter has not been able to find a supportive community in her church or school, she has 300 Facebook friends. While the daughter says this gives her a feeling of connectedness, her mother says, “I’m not sure how valid that feeling is.”

How many programs are too many?

Social relationships have also changed and parents are left feeling ill equipped or powerless to deal with some of them. Either for the sake of intervention, or because they feel the need to equip children with additional skills in an increasingly competitive world, or because they want to keep children from getting into trouble, parents have filled the lives of their children with programs.

Principals in Canada’s Mennonite schools witness daily the stresses and anxieties that weigh heavily on parents. Like the one who wonders, “What do I do as a parent that is good for my child? What do I do if I don’t enroll them in a sport activity? Am I a bad parent if I do less than my maximum to help them get skills? Not filling their time feels like I am ignoring my responsibilities.”

These same principals witness parents who are “running” as soon as their children are out of school. And as community programs and sports dominate more of their students’ lives, they see the results in school, including tired children coming to class.

On the other hand, parents say that by keeping their children busy, they stay out of trouble. But running around to programs means less family time to sit around the dinner table or attend church together.

The busyness and structure imposed on children is also noticeable in how they are at a loss to use free time when it is given to them. “We notice that they are so programmed that they don’t know how to fill free time with creative things,” observes John Sawatzky, principal at Winnipeg Mennonite Elementary School. “Often the play they resort to is what they have seen on video games or movies.”

“There is a growing isolation despite growing activity,” suggests Darryl Loewen, principal of Mennonite Collegiate Institute, Gretna, Man.

The ‘hovering’ parent syndrome

Parents want desperately for their kids to succeed. “In Kindergarten, they want their children to be connected,” says Shawn Burkinshaw, principal at MEI Elementary, Abbotsford, B.C. “When that doesn’t happen quickly, or with the right friends, a bit of panic sets in. Our primary discussions with parents are around relationship issues. In my 15 years as principal, this is becoming more prevalent earlier on. We sense parents are becoming more and more involved. . . . They try to jump in and ‘save’ their kids or fix it for them more so than in the past.”

Some parents hover over their children during their early years in school, but now “ ‘helicopter parents’ are weighing in heavily right even into the university years,” says MEI Secondary principal David Neufeld. “They want to see their children be successful. It’s their way of factoring into their children’s lives.” It’s no longer unheard of for parents to accompany their young-adult children to visit a university professor to discuss a grade.

Giesbrecht is aware of the tension that parents feel. “This generation of parents really wants to be engaged,” she says. “For some, the school might be the only place where they can meet their children’s friends. For the kids I see, they like their parents at a close distance. Kids need a space to simply be, to grow and test, not always be ‘daughter of . . . .’ ”

How schools are helping

“The hunger of parents for help and education has surprised me the most,” says Heather Smith, MEI Middle School principal. “Parents are walking in off the street seeking help.”

This is the second year the school has run a series of monthly meetings for parents throughout the school year addressing parenting issues and challenges. The “i-Parent” sessions, which attempt to build connections between parents and their children, attract up to 180 parents. They are run by Currie, who was also a former pastor of one of MEI’s supporting churches. “The school and church are being called into a role that is unexpected,” Smith says. “We are working hard to partner with our churches, youth pastors and parents in talking about issues.”

Menno Simons Christian School will also be offering a workshop for parents that focuses on raising children in this technological age. “Parents are coming to us for advice,” says Thiessen. “This is the most current issue that parents are having to deal with.”

The risks children face

A mother of two pre-teen daughters is both concerned and sad that today’s society puts so much pressure on children to give up their innocence at a very young age. “There is a lot of pressure on families to see this as normal, and you really feel like you are swimming against the current when you say no,” she says. “Both my husband and I find it takes up a lot of energy to discern what is healthy and optimal for our children. The pressure to push our kids to places they are not ready for is so pervasive these days. Saying no, we’re going to do it this way, to your children can give you a bit of a lonely feeling.”

Giesbrecht agrees. “Kids have more money, more things targeted at them. The messages they receive from the music industry and businesses are that they are ready to drink, to have sexual activity, to own a car.”

It takes a church to raise a child

“So many parents are desperately trying to be friends to their children, but it’s not what they need,” observes a parent. “They need us to be their parents, to be the responsible adults in their lives.”

In his book Hold on to Your Kids, Gordon Neufeld writes, “Parents haven’t changed. . . . The fundamental nature of children has also not changed. . . . What has changed is the culture in which we are rearing our children. . . . For the first time in history young people are turning for instruction, modelling and guidance not to mothers, fathers and teachers and other responsible adults, but to people whom nature never intended to place in a parenting role—their own peers.”

He argues that the task of raising children needs to be shared. In this age of mobility and loss of the extended family, he asks, “Where are the adult mentors to help guide our adolescents? Our children are growing up peer rich and adult poor.”

“Quite apart from religion, the church

. . . functioned as an important supporting cast for parents and an attachment village for children,” he writes. But today many churches separate the family as they enter the door, inadvertently preventing these vital intergenerational connections.

“[The role of] the church should [be to] unapologetically support parents in their role as the primary model for their children,” says Linda Loewen, the mother of two daughters and a member of Home Street Mennonite Church, Winnipeg. “It should be a place where kids can hang onto their innocence and parents can hang onto their authority and respect.”

“Our life as parents is easier because we go to church,” says Loewen. “The church reinforces what we say to our children. Our church is very strong on intergenerational connections. It is easier for us to raise our children because of these natural connections.”

Some parents are able to find the support they need in small groups within the church, where they can talk about things quite honestly, learn from each other and practise accountability.

But what happens when children’s activities draw families away from their church support structures?

“When the children were young it was easier to draw upon church resources, such as small groups and ‘Mothers’ Afternoon Out,’ but as the children get older the family has stepped aside from some of those involvements,” a parent admits. “When you need it most, it seems harder to get,” he says of the support he found in the church. “We are drowning in our own worlds and there is little accountability to each other as parents.”

What can the church do better if Currie is right in his estimate that “over 80 percent of teenagers from Christian homes are leaving their faith after they graduate from high school”? He believes the church needs to do a better job of coaching parents and giving them the supports and skills they need for the job, lamenting that, “what tends to happen in our churches is that we do a message on family, do one talk and run some six-week session during the year, and then we feel we’ve done our bit. We need to do ongoing resourcing for families and parents” who want to raise their children in the Christian faith.

The unidentified parents quoted asked for anonymity for their children’s sake.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.