The ability to see clearly is an important sense to us as Christians and as Mennonites: our theology, The Anabaptist Vision; our music, “Be Thou My Vision”; our scripture, “Without a vision, the people perish.” Mennonite education at its best gives our church a special kind of seeing—akin to high definition or 3D. I call that hindsight, foresight and insight.

A Princeton historian, Harris Harbison, once said, “The goal of the liberal arts is to provide hindsight and foresight in this universe of things and events. The part of Christian belief is to provide insight, which is of crucial significance for living.”

I want to explore these three dimensions of seeing with more direct application to the distinctiveness of Mennonite education:

Hindsight

Hindsight is the ability to see what has come before. And that can only happen if a firm foundation of one’s past is communicated with clarity and conviction over and over again. In Deuteronomy 4: 5-10, as Moses tells his people of God’s new laws for them, he is most concerned about them not retelling the story—and keeping the covenant alive—for the youth and future generations. Moses says, “Watch out. Be careful never to forget what you have seen God doing for you. Tell your children and your grandchildren about the glorious miracles he did.”

Moses invokes all kinds of “memory cues” for keeping hindsight alive, saying, “Impress these commandments on your children in this way: Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up. Tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Write them on the doorframes of your houses and on your gates.”

One way to practice hindsight is to remember to tell the stories you learned while at church, at camp, at Rockway Mennonite Collegiate, at Conrad Grebel University College, at Canadian Mennonite University, at seminary or any other place where Mennonite education is practised!

Every Mennonite church and school has its own story. Grebel’s namesake, Conrad Grebel, was an unlikely Anabaptist hero. He was born into a wealthy, leading family in Zurich, Switzerland. He dressed in elegant, regal attire. He was extremely well educated. His father used his political connections to gain scholarships for him in three leading universities of the day—in Vienna, Paris and Rome. But Grebel got into trouble at all three universities, and he ran out of his father’s money. He came home without earning a degree! Sounds like a real loser!

And yet he prevailed. He became the first Anabaptist. He was dubbed “the ringleader” of this new “radical” Christian ministry. Through lively debates and provocative letters and speeches, Grebel first articulated the need for the Reformation to go a step further, to embrace a new church that favoured a voluntary Christian fellowship—a gathered free church of believers, based on the New Testament. He refused to baptize his daughter Isabella, and performed the first adult baptism in Zurich in January 1525.

For these “treasonous” acts he was arrested, imprisoned and later died before he reached his 30th birthday. His entire Christian ministry was compressed into the last four years of his life, and his powerful witness as an Anabaptist did not emerge until the last 18 months of his life. But what an amazing and history-altering 18 months Grebel lived! Our students in residence, many of whom are not Mennonite, are attracted and empowered by his story.

This year at our college retreat for Grebel students we also told the story of Harvey Taves, one of the founders of this institution. Here was a man who, before his untimely death at age 39, worked tirelessly and patiently for six years in the late 1950s to get the Mennonites in Ontario to embrace the idea of starting a Mennonite college on a secular university campus.

Detractors on the right dismissed the idea of a Mennonite college as “too worldly” or “too expensive.” Detractors on the left, many with ties to Goshen College in Indiana, dismissed the idea because a Waterloo campus would compete with Goshen for students and donors. To quote a leading U. S. Mennonite scholar of the day, “There would be too few qualified academics in Canada to do the job right!”

Taves was not to be outdone, though. Without being dismissive or discouraged with either of these formidable blocs of naysayers, he quietly worked behind the scenes to line up support. Shortly before Grebel’s charter was finally granted in 1961, Taves wrote, “One thing seems absolutely certain to me, and that is that the young person who maintains his faith in the face of opposition is in a much better position to represent that faith once he enters professional life. For this reason, starting a Mennonite college that is affiliated with the UW [University of Waterloo] is worth the risk.”

Most of our stories about Mennonite education are more personal. For me, at my alma mater, Bethel College, a Mennonite school in Kansas, the experience of a Mennonite history class—a class I really didn’t want to take—made an indelible impression.

The final unit of the course, American Mennonites and War, culminated with a film that celebrated Mennonites’ steadfast devotion to faith in the face of war. The only note I took that day was a statement made by its narrator, a Mennonite historian. “War is good for Mennonites,” he said. “It brings out their best.” Scribbled in the margin, I wrote, “What? You’ve got to be kidding.”

Eight years later, I wrote a dissertation for my Ph.D. in communication that explored that very subject. And I have been writing about various aspects of rhetoric of the marginalized and Mennonite faithfulness to church and state ever since.

These stories are not unique. Graduates of Mennonite institutions have many formative stories that have made all the difference in their lives, so we all must tell our stories, and we must tell and retell them in our churches and in our communities. Hindsight builds a “firm foundation” of knowledge and faith principles that can be transferred from one generation to the next. Hindsight fortifies us and grounds us. There’s a reason we say, “Hindsight is 20/20.”

But if our vision is reduced to just looking in our rear-view mirror, we can become overly cautious and risk-averse. We get stuck in neutral. So we also need another way of seeing.

Foresight

Foresight is the ability to see what is coming, to be “ahead of the curve.” Foresight pushes us and makes sure we don’t get too complacent, too insulated, too comfortable! Foresight demands we embrace our future full-throttle!

In an educational context, this means asking whether my college experience will prepare me for the future, for a meaningful, relevant and marketable career.

Our Mennonite schools are all eager to champion academic excellence, to celebrate the achievements of our students and faculty, and to roll out new academic programs that are “cutting edge.” And we all have many distinguished alums!

Given Grebel’s unique relationship with UW—rated Canada’s most innovative university—we are especially well-equipped to “hitch our wagon” to this “shooting star.” But at Grebel we push the boundaries of academic excellence with an eye to balance, because we are also eager to promote a vibrant future of “countercultural” education, to embrace “peculiar peoplehood” for the 21st century. We want to push the frontiers of what it means to study peace in our culturally diverse world and so we are excited to launch our new Mennonite Savings and Credit Union Centre for Peace Advancement in 2014. We are looking ahead, not just to prepare our students for a meaningful career, but for a meaningful life.

This attention to balance runs counter to the fragmentation and extreme specialization that is common in the stand-alone secular research university or trade school. Some educators have called this trend, “The Home Depot approach to education,” where there is “no differentiation between consumption and digestion.” As the Chronicle of Higher Education has reported, like Home Depot, “college degrees can become like a vast collection of courses, stacked up like sinks and lumber for do-it-yourselfers to try to assemble on their own into a meaningful whole.” Our Mennonite schools counter that trend by meeting the strong push of specialization with the gentle pull of community accountability.

For example, this past spring at Grebel we celebrated the accomplishments of two students both named “Caleb.” Caleb Gingrich wrote the top research essay in engineering in all Ontario universities with his paper, “Industrial symbiosis: Current understandings and needed ecology and economic influences,” and Caleb Redekop won the C. Henry Smith Peace Oratory Contest at Grebel with “The church needs to occupy.” The tale of the two Calebs is about the push of specialization meeting with the pull of community accountability.

So foresight is important, but if just foresight is our vision, then we are only chasing the self-serving next big thing. Even community-building initiatives, removed from a larger ethic of care and discipleship, can foster shortsightedness.

Insight

Insight is discernment. It is the power of apprehending the inner nature of things. It is this inner way of seeing found in Romans 12:2, where Paul says, “Do not be conformed to this age, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, so that you may discern what is the good, pleasing and perfect will of God.”

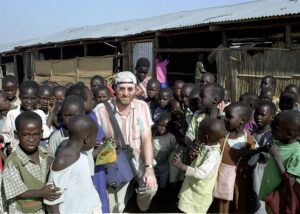

Our students in Mennonite institutions are encouraged to seek insight—to practise shalom—by learning to serve others in Christ-centred discipleship. CMU has a signature service/learning program called Outtatown, a six-month-to-a-year-long service commitment to South Africa or Guatemala. Rockway has an all-day Envirothon/Servithon day in Kitchener-Waterloo, and trips to China, Guatemala, France-Germany and Florida. Grebel has service/learning trips to South Africa, Palestine/Israel, London, and many places in North America.

These kinds of experiences are formative for students and make real our aim to educate the whole student intellectually, emotionally, socially and spiritually.

One of the best ways to remember the importance of service to others is to hear the ancient words of St. Francis of Assisi, the world’s most revered patron saint of animals, the environment and the poor. In the year 1223, a young apprentice monk expressed frustration because Francis, his mentor, was late yet again for a speaking engagement. Francis had stopped three times along the road to attend to a homeless man and a wounded animal, and to pray for some beautiful birds. Francis turned to his young, impatient colleague and said in his humble and gentle way, “My friend, there is no use walking anywhere to preach, unless our walking is our preaching.”

Insight tempers the extremes of foresight—opportunism that is merely fast-tracking or self-promoting—and asks us always to think about opportunities to advance the cause of others. Insight teaches us never to miss an opportunity to witness shalom by performing works of mercy, extending generosity, supporting community and serving the church.

Without insight we have not captured the distinctive of Mennonite education that says knowledge and practice are not sufficient unless they are connected to a witness grounded in Christ, committed to peace and practised in community.

Conclusion

Our Mennonite schools prepare us for seeing in many ways. Hindsight is built by passing the faith traditions to future generations through the telling of foundational stories. Foresight is built by seizing opportunities to advance and extend our knowledge of the world and connections to the world. Insight is built by a distinctive witness of “shalom,” steeped in the good news of the resurrected Jesus and practised in community.

Susan Schultz Huxman is president of Conrad Grebel University College.

See also:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.